The HIV/AIDS pandemic is driven not only by the spread of the disease among vulnerable and marginalized populations, but also by the unwillingness of transnational drug companies to allow the widespread use of generic antiretroviral treatment to challenge their patent control. Simply put, intellectual property rights and free trade agreements have undercut the ability of countries to provide generic antiretroviral drugs to save people with HIV/AIDS.

In spite of a formal agreement allowing the most affected countries to get generic drugs to those who need them, the large pharmaceutical companies, the US government and other governments have continued to use unfair trade rules and procedures to throw up obstacle after obstacle to protect the patent regimes that ensure that Big Pharma profits from their drug sales.

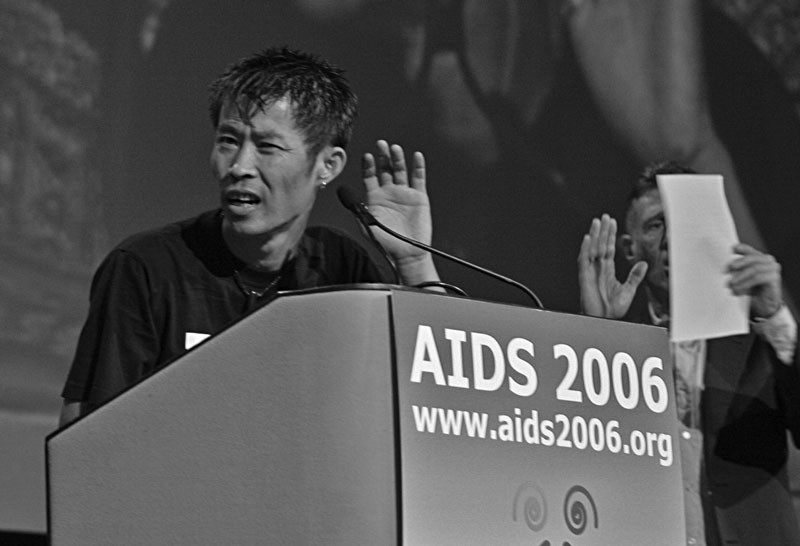

Stephen Lewis, the UN special envoy for AIDS in Africa, spoke out on the subject during the XVI International AIDS Conference in Toronto in August 2006. Lewis said, “The problem is the big pharmaceutical companies. They are always stalling, and because governments—-both Liberal and Conservative—-don’t seem to have the backbone to stand up to these pharmaceutical companies, this never gets resolved. What you have to do here is issue a compulsory license. That’s the procedure. If the big pharma companies will not grant a voluntary license to the generic companies, then the government steps in and amends the regulations and delivers a compulsory license, which the legislation allows them to do.”

Lewis concluded, “The fact that the government hasn’t done this is what is stalling this process. We’ll be three and a half to four years before a pill ever leaves Canada, which, in the context of the pandemic, is outrageous.”

This is the case in spite of a commitment from the Canadian government—-passed into law in May 2004 and known alternately as the Jean Chretien Pledge to Africa or Canada’s Access to Medicines Regime—-to provide authorization for export of generic drugs to address public health epidemics. Two and a half years after it became law, not one generic antiretroviral pill has yet been sent to Africa from Canada.

At the time, the Canadian government’s pledge to Africa was hailed as a major breakthrough. Canada was to become the first Group of Eight (G8) nation to implement World Trade Organization agreements that allow hard-hit countries to import critically needed cheaper medicines. This step was taken in accordance with decisions of the World Trade Organization going back to the Doha Declaration of 2001. The Doha Declaration, adopted under intense pressure from global civil society, placed public health above private commercial interests and affirmed the right of countries to use safeguards such as compulsory licenses to override patents in cases of public health crises. On August 30, 2003, the WTO General Council further resolved that developed nations could export low-cost generic drugs to developing nations in order to address public health epidemics.

According to Rachel Kiddell-Monroe, the Canadian head of Doctors Without Borders/Medecins Sans Frontiers, her organization was among the first to test the Doha Declaration by placing an order to the Canadian government for antiretroviral drugs for use in their field projects. But, Kiddel-Monroe confirms, “two years on, not a single pill has left Canada.”

Why Canada has still not been able to export a single generic antiretroviral drug is the burning question. Prime Minister Harper did not attend the International AIDS Conference in Toronto to answer that question. His Minister of Health, Tony Clement, said at the time that Canada would make a major announcement about the government’s commitment to fight HIV/AIDS, but no announcement has yet been made. The real reason for the drugs not getting there may lie in the machinations of the pharmaceutical companies seeking to defend their patents, the governments’ complicity, and the constraints imposed nationally and internationally by intellectual property laws and binding agreements.

In the face of numerous delays, Apotex has given up trying to get a voluntary license and is now asking for a compulsory license to export their generic drug APO-TriAvir, an improved treatment that combines three antiretroviral drugs, each of which is patented.

In a recent Doctors Without Borders Canada analysis called “Neither Expeditious, Nor A Solution,” the authors conclude that the WTO’s 2003 decision on allowing the export of life-saving generic drugs is, in fact, unworkable. Doctors Without Borders Canada argues that the WTO must propose alternative mechanisms that meet health needs, are expeditious, and take into account the global reality of drug procurement. In Canada they are asking that the Pledge to Africa be reviewed and that the “fundamental flaws in the legislation” be addressed. Furthermore, they are asking that Canada use its influence at the WTO to remedy the constraints of WTO rules governing the delivery of generic medicines to those in need.

Trading Away People’s Health: TRIPS-plus

Even if the Doha Declaration were to be implemented, numerous recently signed free trade agreements contain clauses that effectively restrict countries from importing or manufacturing antiretroviral generic drugs. According to Rohit Malpani, policy advisor for Oxfam International, the actions of the US government are directly contributing to the lack of access to generic drugs for those who need them most. “Under the name of free trade, the US is pushing for a monopoly on new medicines, thus driving up costs for some of the world’s poorest people,” says Malpani.

The US is introducing stronger intellectual property rights in bilateral trade agreements that will deny developing countries the right to access affordable drugs for the millions of people who need them. This is being achieved by expanding upon the intellectual property rights already guaranteed by the WTO’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), and has therefore become known as TRIPS-plus.

The TRIPS-plus provisions include rules that will turn national drug regulatory authorities into enforcers of patents, as well as restrictions that will limit the ability of countries to use compulsory licenses as legal tools to ensure access to low-cost medicines. TRIPS-plus undermines the Doha Declaration and attacks the flexibilities and safeguards it reaffirmed. Its provisions are appearing in already-signed agreements such as the Central American Free Trade Agreement, the US-Singapore Free Trade Agreement, and the US-Morocco Free Trade Agreement, and are likely to appear in trade agreements being negotiated with Thailand, Panama, the Andean Countries (Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru) and countries of the Southern African Custom Union.

In a briefing note circulated at the International AIDS Conference in August, Doctors Without Borders warned that, “one by one, countries are trading away their people’s health in ‘free trade’ agreements with the United States. These countries are being pushed to accept extremely restrictive intellectual property provisions that could put an end to competition from generic medicine producers.” These trade agreements effectively require countries to surrender their right to deliver public health care to their people. Meanwhile, UNAIDS estimates that 40 million people are presently living with—-and dying from—-HIV/AIDS.

The fact is that an estimated five to six million people will die in the next two years in low- and middle-income countries if they do not receive antiretroviral treatment. As of June 2006, only 1.65 million people living with HIV in resource-poor countries were receiving antiretroviral treatment, out of 6.8 million in need. According to World Health Organization HIV and AIDS Director Dr. Kevin De Cock, “We have reached just one-quarter of the people in need in low- and middle-income countries, and the number of those who need treatment will continue to grow. Our efforts to overcome the obstacles to treatment access must grow even faster.”

Meanwhile, drug companies continue to garner massive profits. The pharmaceutical industry is, in fact, the most profitable industry ever, pulling in an average annual profit rate of 18 percent over the past 25 years (Marcia Angell, The Truth about the Drug Companies, 2004). Access to generic drugs makes a huge difference in a country�s ability to meet its public health commitments.

Thailand and Korea—-A Case In Point

Citizens’ movements in Thailand and South Korea are fighting to keep their governments from being pushed into these restrictive US Free Trade Agreements.

At the International AIDS Conference in August, AIDS activists from South Korea proclaimed, “people do not die because of AIDS, but because they do not have access to the medicine.” These activists are deeply concerned that the Free Trade Agreement presently being negotiated between South Korea and the US will increase drug prices, lead to a monopoly for transnational drug companies on essential medicines, and lead to the collapse of their National Health Insurance.

Thailand has been in a bitter struggle as well, already beginning to grapple with the impact of a Free Trade Agreement on people seeking to access affordable drugs for antiretroviral treatment. (Thailand has a large population of people living with HIV/AIDS. There are at least 29,000 new HIV/AIDS cases each year.)

The Thai Network of People Living with AIDS is concerned that under a US Free Trade Agreement “the right to produce patented drugs will be restricted.” They fear that local pharmaceutical companies that currently produce generic antiretroviral medication will be driven out of business.

Inter Press News Service reports that Thailand is currently implementing a treatment program for over 80,000 people based on a generic drug regimen recommended by the World Health Organization. This treatment program is ten times cheaper than patented brand-name equivalents. Patented drugs sold by the big pharmaceutical companies in Thailand can cost up to US$589 per month, while the state-produced equivalent costs US$32 per month.

The implementation of a US Free Trade Agreement with Thailand will seriously compromise access to these generic drug sources. “We fear that if the Thai government accepts the US proposal, doctors in Thailand will face substantial obstacles in providing treatment to their patients living with HIV/AIDS, especially for those that require newer antiretroviral medicines to survive,” says Paul Cawthorne, Doctors Without Borders’ Head of Mission in Thailand.

The Thai Network of People living with AIDS has staged numerous protests (including at the International AIDS Conference), and is working in alliance with other AIDS activists and organizations from Malaysia and South Korea. They are hoping to forge alliances with other groups being threatened in the Free Trade Agreement negotiations, such as farmers and workers from the agricultural sector.

An Appeal from Doctors Without Borders

Doctors Without Borders has issued a worldwide appeal to nations involved in Free Trade negotiations with the US to exclude intellectual property rights from bilateral and regional trade agreements, declaring that, “the devil is in the details.” These “details” include provisions that will dramatically reduce the ability of countries to provide low-cost quality medicines for their citizens. Because the Bush Administration has been unable to achieve consensus for its neo-liberal agenda at World Trade Organization negotiations, it is trying though these Free Trade bilateral and regional agreements to “extend the exclusive marketing position pharmaceutical firms have in the medicine market.” Doctors Without Borders further states this will “turn national drug regulatory agencies, whose job is to ensure the safety, quality and efficacy of medicines, into enforcers of the private property rights of corporations.”

Doctors Without Borders urges that “health should not be under negotiation in these talks. This is the only way that governments can uphold their right—-and obligation—-to protect public health and guarantee access to essential medicines for their people.”

There is hope

At the XVI International AIDS Conference in August, there were some hopeful signs in the fight against HIV/AIDS. Botswana reported that HIV mortality rates have fallen since the roll-out of a free antiretroviral therapy program. Although the findings are preliminary, they indicate that antiretroviral therapy is reducing premature mortality in Botswana. Botswana’s antiretroviral therapy was introduced in 2002, and has proven to be one of the most successful, reaching 85 percent of those estimated to need treatment. (Unfortunately, however, Botswana is on the list of countries slated for US Free Trade Agreement discussions, which will surely jeopardize the future of this program.)

Another hopeful sign is on the preventative side, with the emerging great world movement of women, grandmothers, and youth organizing to address issues of poverty, gender and healthy communities through economic and social community development. As communities organize themselves, they are building the power base to influence and pressure their governments not to sign agreements that will trade away the public health of their communities. Likewise, citizens in “developed” countries such as Canada have to stand in global solidarity with these movements, pressuring our governments and challenging the power of transnational corporations and their trade agreements.

Don Kossick is a founding member of the Making the Links radio collective, www.makingthelinksradio.ca. He has worked in community organizing initiatives internationally and in Canada for many years.

To start your subscription immediately, call (306) 525-2949, email us, or subscribe online.