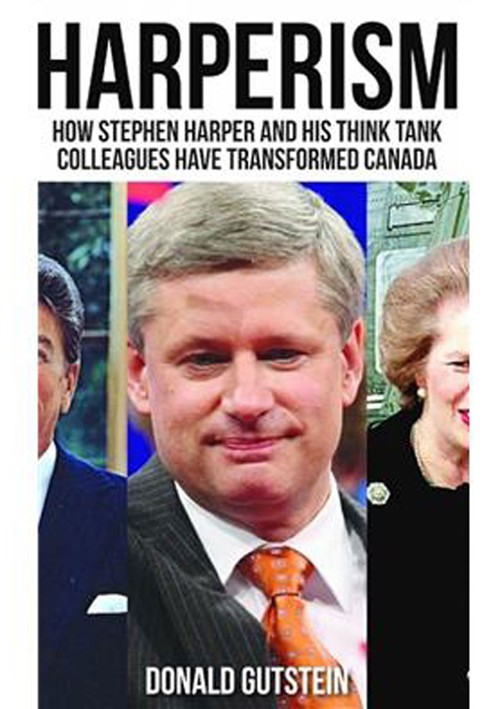

Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan so transformed the politics of the countries they governed that new political orders were named after them. In Harperism, Donald Gutstein attempts to make the same case for current Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper.

For Gutstein, Harper’s rise marks a culminating point in the successful bid of neoliberal think tanks and right-wing media personalities to define the conventional wisdom in Canada. Harper’s success is a product of neoliberal politics, then, and not their source. Following thinkers like David Harvey, Gutstein gives a helpful account of the emergence of neoliberalism in the postwar world, charting the rise of intellectuals like Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman and their role in creating the Mont Pelerin Sociey, which laid the intellectual foundations for a new era of free market ideology.

Gutstein is careful to dispel the myth that neoliberal governance means a small state. It’s just that the neoliberal state is committed to creating new markets and ensuring their success, no matter the cost, in place of providing social services. Gutstein understands that neoliberalism had penetrated the thinking of Canada’s political class long before Harper’s ascension to the leadership of the Conservative Party.

Far too many people in the anti-Harper camp lay all of Canada’s problems at Harper’s feet, avoiding a more systemic and historical understanding of how we got to this place. Gutstein highlights the Mulroney government’s push for free trade, the deep cuts of the Chretien years, and how even the NDP has been largely unwilling to challenge the neoliberal framework. Harper and his ideological comrades simply come off as the most committed and ruthless of the modern neoliberal political class.

Gutstein’s chronicling of the workings of Harper and his allies in think tanks and the media is the real strength of Harperism. Gutstein charts how the rise of think tanks like B.C.’s Fraser Institute emerged across the West in a strategic assault on social democracy. And think tanks would mean little without accomplices in media and journalism. Hayek understood that there needed to be a class of “professional secondhand dealers in ideas” to communicate neoliberal ideas to the public in an accessible way. Slowly but surely this renewed free market ideology was disseminated through major media outlets.

Far from an indictment of a lone politician, Harperism lays out the incestuous neoliberal nexus of Canadian think tanks, media, and governance.

Gutstein’s fourth chapter, “Liberate Dead Capital on First Nations Reserves,” shows how Tom Flanagan and co-authors Christopher Alcantra and André Le Dressay’s 2010 book Beyond The Indian Act: Restoring Aboriginal Property Rights was successfully pushed by neoliberal think tanks like the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. The book’s reception and its thesis – that creating private land title on reserves would usher First Nations into the modern capitalist economy and allow them to lift themselves from poverty – was soon being discussed across major media outlets.

Beyond the Indian Act draws heavily on economist Hernando de Soto’s work in creating land title for Indigenous peasants in Peru. Following the book’s publication, Canadian think tanks and foundations played host to numerous events with Soto, promoting private ownership (fee simple title) as the answer to First Nations poverty. Soon, government officials and MPs were signaling their support to reforming the Indian Act to allow land title. The federal government’s reforms to the Indian Act were derailed in the short term by the massive groundswell of Indigenous activism that became known as Idle No More.

Gutstein also shows how the discussion around right-wing polemicist Ezra Levant’s book Ethical Oil followed a similar path of embrace from think tanks to reviews in the media to official government talking points.

Gutstein’s documentation of the neoliberal idea pipeline leaves the reader with a horrible impression of what passes for journalism in Canada. Gutstein shows how columnists like Andrew Coyne and Terence Corcoran are hopelessly compromised by their membership in various neoliberal think tanks and foundations – ties never disclosed when they write about policy issues. And the media’s role as neoliberal mouthpiece isn’t confined to publications that wear their ideology on their sleeve like the National Post and the Sun newspapers (recently bought by Postmedia). The Canadian Press, Globe and Mail, and even the liberal Toronto Star act as conduits that keep policy debate within neoliberal parameters.

Do all of the examples contained in Gutstein’s book make the case for something we can name Harperism? There’s a revolving door of individuals who all pass through think tanks, media, and government that have supported Harper’s policies and the Conservative Party itself. The case for Harperism is strong.

Gutstein also shows how an incremental approach has been a major factor in Harper’s governance. A cut here, a new policy there – the monolith emerges incrementally. Take raising Old Age Security eligibility to age 67. It doesn’t affect Canadians immediately, as they reckon with the immediate challenges of a discouraging job market, runaway housing costs, and private debt. Likewise, few Canadians feel the immediate effects of Harper’s climate crisis obstructionism.

It took the Reform and Conservative parties many years to shake off the public fears that they would introduce a two-tier healthcare system. But sure enough, we see Harper reducing federal health care dollars over the next several years at a time when many provinces are struggling to close their budget deficits. This resulting crisis may only come to a head after Harper has left office.

Given the tight policy window Harper has created, introduction of private care into Canada’s healthcare system, like the use of public-private partnerships throughout the public sector, can seem a fait accompli. Meanwhile, Gutstein sees a Liberal Party that seeks to distinguish itself from Harper in style, through the sheer force of Justin Trudeau’s personality, but not in substance, while Thomas Mulcair’s NDP seems as reticent to raise taxes on the rich as any dedicated neoliberal. Canadians should recall that when Margaret Thatcher was once asked what her greatest accomplishment was, she replied, “New Labour.”

As Gutstein notes in his conclusion:

“The Institute of Economic Affairs, the first neoliberal think tank, established the guiding principle for all its publications: make no concessions to existing political or economic realities, but stick to neoliberal doctrine. Neoliberalism’s enemies must do the same if they ever hope to forge the ideas that will eventually replace neoliberalism. Otherwise, Harperism will remain intact for years to come.”

A key weakness in Harperism is Gutstein’s analysis of neoliberalism as a movement. He notes that funding to promote neoliberal ideas comes from wealthy capitalists like Canada’s Thompson family. But Gutstein still portrays the neoliberal offensive of the last 40 years as a movement of right-wing Jacobins responding to the economic crisis of the 1970s.

There is no explicit talk of neoliberalism as a broader class offensive. For neoliberalism isn’t just a reflection of the desires of right-wing ideologues but of a capitalist ruling class that has thrown off the very modest and incomplete regimes of regulation and redistribution found in Western economies after World War Two.

It is neoliberalism’s success that shows the limits of democracy within a capitalist system. And that’s an issue that Gutstein does not address.