In 1966, the government of Manitoba signed over logging rights for an area slightly larger than Portugal to a firm based in Zurich, Switzerland: Monoca A.G. St. Moritz. These 40,000 square miles of Cree, Dene, Anishinaabe, and Métis lands were to form the basis of what Monoca A.G. St. Moritz spokesperson George Litton called, at the time, “the largest single industrial operation in the history of Manitoba.” This operation was the sprawling “Forest Products Complex” that would employ 1,400 people on an annual payroll of $78 million (in 2019 dollars). It was a formative time for Manitoba and for Manitobans, as decades of government planning to monetize the immense forces of nature lying north of the 53rd parallel came to fruition. The first of Manitoba’s great northern dams, at Grand Rapids, had been under construction since 1960. By 1968, it would transmit enough cheap electricity to make the Forest Products Complex – and the government’s long-held vision of a northern “pulp and power” economy – possible, along with a bevy of other energy-guzzling industrial outfits that would define modern Manitoba.

It was a formative time for Manitoba and for Manitobans, as decades of government planning to monetize the immense forces of nature lying north of the 53rd parallel came to fruition.

Like the much older Prairie grain industry, northern pulp, power, and mining industries were driven not by the invisible hand of the market, but by conspicuous spurts of prior state initiative. Generous public financing, in particular, lured capitalists to northern Manitoba and sealed deals. In the early 1960s, on the recommendation of multinational consultant Arthur D. Little Inc., the Manitoba government established three crucial new institutions – the Manitoba Development Authority, the Manitoba Development Fund, and the Committee on Manitoba’s Economic Future – designed to arrange a mass transfer of public money, forests, and other natural resources to private firms. In pursuit of a northern pulp and paper industry, these entrepreneurial agencies led Manitoba into a complex world of multinational firms and financiers, with meetings held in New York City and in various European countries and often brokered by third parties, such as New York-based Parsons and Whittemore Inc., that specialized in acquiring public money for privately owned paper mills in underdeveloped regions. In the end, the unnamed owners of Monoca A.G. St. Moritz and its many affiliates – including New Jersey-based Technopulp Inc. – would receive $608 million (in 2019 dollars) in loans from the Manitoba government along with their inordinate share of the Manitoba forests.

The decades immediately following the Second World War are sometimes remembered as a golden era of capitalism on Turtle Island: a rosy flash when the gains of organized labour waxed in the form of good wages, job security, and a stretching social safety net, and the people who would come to be called “baby boomers” prospered. By some measures, it is true. Real incomes in Canada almost doubled between 1945 and 1975. Consumer spending tripled between 1948 and 1960. “Disposable” income became a thing. After losing the solid returns of the war effort, global capitalism stabilized itself by increasing many workers’ purchasing power, creating new needs, and lending money to governments to build things. Suburbanization encapsulated the process: freshly flush workers bought cars, houses, and lawn mowers in subdivisions hooked up to sprawling new highways, water, sewer, and electricity lines. For bosses, suburbanization was politically savvy, too. War can radicalize people, instilling a dangerous sense of power and dignity in those who fight, pulling back the curtain on the enormity of what human beings are capable of, and incurring feelings of resentment against the authorities who sent them to die. Doling out debt-financed home ownership and pay packets to service the debts helped capital avoid another round of general strikes, like the one Canadian workers mounted after the First World War.

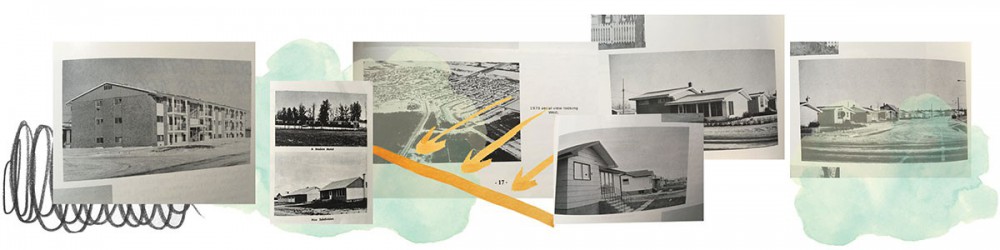

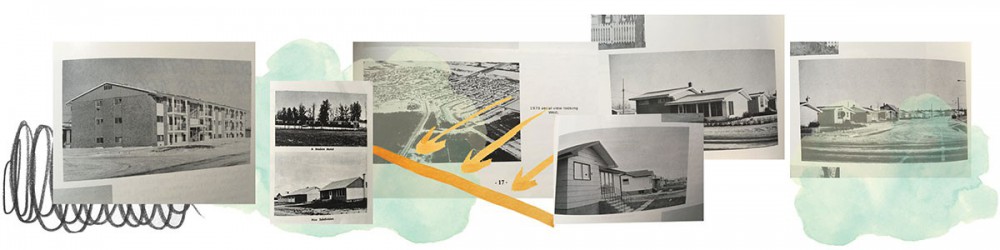

Monoca A.G. St. Moritz opened the Forest Products Complex in phases, starting in 1968, in The Pas, Manitoba. According to Henry Wilson, a former band councillor from the area, “The Pas” – pronounced “The Paw” – comes from the Cree word “opaskwayak,” which translates to “where the land rises.” The town’s population spiked from 5,000 to 8,000 in the years following, as families from across Canada and northern Europe pulled up stakes and sought new lives for themselves in Manitoba’s “gateway to the north.” By 1971, mill workers at The Pas were pumping out 350 tons of pulp and kraft paper and 205,000 board feet of lumber per day. “Kraft” is German for “strength”: the cold-growing spruces and jack pines of northern Manitoba are perfect for making the sturdy paper commonly used for supermarket bags and heavy products such as pet food, barbecue coals, or cement. It was The Pas’s suburban moment. Cookie-cutter bungalows and “modern apartment houses” sprang up on the edges of town. New schools were built. Parents were able to sign their kids up for indoor swimming lessons and indoor hockey for the first time, in newly built facilities. The barroom at the Gateway Hotel hummed on Saturday nights; new cars raced up and down Fischer Avenue (the only paved route to northern Manitoba at the time, built by Depression-era relief workers, and also known as Highway 10). The Depression days of the 1930s – when nearly a thousand jobless workers marched from The Pas’s Ukrainian hall to city hall under the banner, “GIVE US THREE MEALS A DAY, OR A JOB, OR SEND US TO JAIL” – were firmly in the rearview mirror, it seemed.

“The Pas” – pronounced “The Paw” – comes from the Cree word “opaskwayak,” which translates to “where the land rises.” The town’s population spiked from 5,000 to 8,000 in the years following, as families from across Canada and northern Europe pulled up stakes and sought new lives for themselves in Manitoba’s “gateway to the north.”

North America’s post–Second World War boom did more than expand bank accounts and built environments – it changed people. “Suburbanites are a special breed of people,” geographer David Harvey writes, “whose political subjectivity is shaped by their daily living experiences in the same way that the imprisoned Italian communist leader Antonio Gramsci envisaged what he called Americanism and Fordism producing a new kind of human subject through factory labour.” Historians tell us that the widening postwar realm of consumption nudged people to think of themselves more as shoppers than as workers; to aim their hopes and their labours toward acquiring the latest things for their families rather than, for instance, developing their knowledge, creativity, and relations with other people. Cold War anti-communism combined with the modernist spirit of the day to encourage Canadian workers to feel that the newest things and places produced by capitalism were superior advancements, subtly disparaging everything – and everyone – else. It was also a time in which certain so-called ethnic barriers among European-descended peoples were broken down to a significant extent, and a broader white identity was consolidated. Many of Canada’s upwardly mobile workers in this era came from groups – such as Ukrainians, Poles, Germans, Italians, and Jewish people – that were gaining access to the country’s mainstream white Anglo-Saxon institutions for the first time. All of these changes tended toward a common result: they brought workers into Canada’s capitalist fold, luring them into accepting and identifying with a system that exploited them and all its inherent, long-standing vices: its endless violence, racism, misogyny, and inequality.

By 1968, The Pas – a 5,000-year-old human settlement – had, for 60 years, consisted of four separate and unequal types of places differentiated by race and class but stitched together to form a more or less continuous town around the steel bridge where the Canadian National Railway (CNR) crossed the Saskatchewan River. Those four places were the Opaskwayak Cree Nation (OCN); a series of Métis settlements; a few white working-class neighbourhoods; and a wealthy area of white industrialists, merchants, and professionals. The modern Cree and Métis communities, forged by families creatively resisting Canadian invasion, predated the white settlements. The founders of the white town built it on a foundation of frontier racism, driving the OCN at gunpoint across the Saskatchewan River and erecting their town on the OCN’s former reserve site. Residents of the OCN were then banned from crossing the river into town, as dictated by the Canadian apartheid policy today known as the pass system. The legal boundary of the new town left the Métis settlements of Young’s Point, Big Eddy, and Umpherville on the other side of the line, conveniently enabling the town pioneers to deny Métis families services that white residents enjoyed. A Métis settlement within town boundaries, the Dion Camp, was destroyed. Many, if not most, Métis people who remained in town were compelled to pass as white.

Other Métis settlements persisted, remarkably, in resistance to both the town’s efforts to freeze them out and a total lack of recognition from the Canadian state. Young’s Point, a community of self-built houses just to the south of the white town, was one such refuge for Métis families as well as for Cree families denied Indian status by Canada and thus barred by the Indian agent from living at the OCN. Young’s Point residents maintained an impressive level of Cree Métis tradition and autonomy. Trapping, hunting, farming, berry picking and carrying out their own approaches to medicine, law, and mutual aid, Young’s Point residents unapologetically defied the persecution of Métis ways of life that prevailed among Canadians in the 20th century. Antonia Brommeland, born in Young’s Point in 1927, the granddaughter of a local medicine man, remarked on the community’s collective ethic, in conversation with Sara Geirholm and Amanda Smashnuk in the 1997 book What it is to be a Métis: “Everybody took care of each other. One year Mom said Dad was late coming back from the trap lines so she said I guess we’re not going to have no Christmas this year. There’s not going to be no Santa Claus. We said Santa Claus and we seen candies and treats and then she used to make us a dress each for Christmas present and uh she went out here sure enough my neighbour Rachel Ducharme had came down and she had a bag full of stuff sitting there [...] at the door. So she come back and she said oh yeah I thought I heard something up there last night. That’s what it was, Santa Claus had come.”

The legal boundary of the new town left the Métis settlements of Young’s Point, Big Eddy, and Umpherville on the other side of the line, conveniently enabling the town pioneers to deny Métis families services that white residents enjoyed.

Margaret Jaffray, the granddaughter of Josiah Young, one of the community’s founders, was born in a small house in Young’s Point just before the Great Depression. Jaffray, speaking to Joanne Burrows, Joanne Enders, and Mike Evans, explained that the spirit of mutual aid in Young’s Point was related to a level of political autonomy the community practised: “That’s what they did in those days. They looked after each other. If the father is gone, or abandoned his children, everybody took in someone. And that’s the same if a person, like drank or neglected their children, they would just go right in the house and take the children. And they can’t say anything. We had no laws. We just had our own laws.”

It is interesting to observe that white workers, to the extent that they were anaesthetized by better wages, home ownership, and new cars, were out of step with most of the working people of the world. If those were years of working-class political retreat, the white flags were for white workers. Colonized people were busy taking over the world. So they were, in their own way, in Young’s Point, Big Eddy, Umpherville, and the OCN. At 3 p.m. on January 13, 1964, residents of the former three communities formed The Pas Métis Council to fight for Métis rights and to improve living conditions in the settlements – most urgently, “[p]roblems of inadequate housing, lack of hydro and telephone.” “There was an extremely good representation from all the Metis settlements and the group were certainly eager and enthusiastic, and felt that such an organization was long overdue,” one report read.

Residents of the OCN, too, began taking back control following hard-won 1951 amendments to the Indian Act – the first significant changes to the Act in 50 years – that weakened the role of Indian agents and abolished the pass system. A major victory came in 1965, when families were no longer forced to send their children to Indian residential schools and the public-school system was integrated. In 1968, OCN residents opened a five-person band office in a small house, and this became a launching pad for regaining autonomy over governance, industries, infrastructure, and more.

On January 13, 1964, residents of the former three communities formed The Pas Métis Council to fight for Métis rights and to improve living conditions in the settlements – most urgently, “[p]roblems of inadequate housing, lack of hydro and telephone.”

White people in The Pas lashed out at the transformations taking place literally all around them. Wilson, who formerly served as an OCN band councillor, was born in 1943, the son of a trapper and a nurse’s aide. He tells me that the “racial boundaries” and “racial fights” in The Pas got much worse in the 1960s. The town’s most popular teen hangout and symbol of all that was new and worldly, the Lido Theatre cinema, was racially segregated. The Legion in town didn’t acknowledge Cree Second World War veterans. The Gateway Hotel lifted its ban on serving Cree people but segregated the barroom. Integration of the town’s schools, in particular, got under the skin of whites. Alvin Merasty, a friend of Wilson’s, was also born and raised in the OCN. He attended school in The Pas when integration was just beginning and told me a story about two second-grade boys from the OCN who had likewise attended school in The Pas. One day, in 1967, their teacher brought them to the front of the classroom and asked their fellow students, “What is wrong with these children?” A white girl replied, “they’re dirty, uncivilized Indians.” “That’s right,” said the teacher. The boys were taken to have their hair cut and put in funny, cheap, ill-fitting “civilized” clothes. (“Remember those belts?” Alvin asks Wilson, “those cheap 50-cent belts they made us wear, that said “THE PAS” on the back?”) The teacher brought the boys back to the front of the class. “Now what is wrong with these boys?” she asked. “Nothing,” a little white boy answered, “they’re clean and civilized now.” “That’s correct,” the teacher replied. The boys never recovered from the episode, according to Alvin. Cree children, of course, had been subject to similar abuses for decades in Indian residential schools. But this was different – now the abuse functioned as miseducation for other children, pumping out young tormenters whom Native students were forced to contend with for the rest of their school days.

Doris Young, an administrator at the University College of the North (UCN) in The Pas, and a long-time researcher, educator, and community organizer, was born in the OCN in 1940. As Native women, in particular, “we never really felt safe in The Pas,” she tells me. Young authored a report in the 1990s describing the activities of white men who, in the 1950s and 1960s, were known to abduct and assault Cree women and to attack Cree men for attempting to cross the bridge into the white town. Local police, Young reported, looked the other way in these instances, but they were known to stop young Indigenous people in the street, demanding they account for their presence in white parts of The Pas.

Murray Harvey, currently an author of historical fiction about the region, held many prominent positions in The Pas in the postwar years, from publishing the Opasquia Times to serving as chairman of the Forest Products Complex. Harvey, who is Métis but didn’t know it until the 1990s, was born in 1931, the son of a district forester. He grew up in the 7th Street area, one of The Pas’s working-class neighbourhoods. The white town’s racism had long been evident: Cree and Métis people were not hired at the town’s first sawmill – the “Finger mill,” after its owner, Herman Finger – or by the CNR, the town’s largest employer, except in the worst bush camp jobs, and white governments refused to extend services to the Indigenous parts of town. But it was when Indigenous peoples “got their freedom” in the 1950s, Harvey agrees, that anti-Native racism hardened into an everyday practice for whites in The Pas. Before that, Harvey claims, “we never saw them.” As the federal government withdrew from the practice, it seems, everyday white people took apartheid into their own hands.

The growing freedom and militancy of Cree and Métis communities in the 1960s influenced official versions of what the Forest Products Complex was supposed to mean. The Manitoba government’s initial announcement of the project, on March 8, 1966, claimed that the complex would create “4,000 new jobs, 2,000 directly and 2,000 indirectly,” adding that “[s]pecial attention will be given to the people of Indian descent, and half the workers employed could be Indians and Metis.” As the complex neared completion, those numbers shrank but were still significant: 600 jobs would go to Métis and Cree workers, the government said, based on assurances from Litton, who by then was the acting general manager of the complex.

As the federal government withdrew from the practice, it seems, everyday white people took apartheid into their own hands.

There is a hierarchy of workers in the capitalist forest industry, that, roughly speaking, ascends from the point of cutting down the tree to the most technologically complex method of processing it into a final product. Monoca A.G. St. Moritz installed the Cree and Métis people of The Pas in, as Alvin puts it, the most arduous “go freeze your ass off in the bush” jobs: logger, hauler, pulp cutter, ditch digger. Half of this work was contracted to middlemen, much of it piecework with no minimum wage. When local loggers banded together to refuse this type of labour, Monoca A.G. St. Moritz brought in scabs from the north shore of the St. Lawrence river in Québec, as they were already accustomed to piecework.

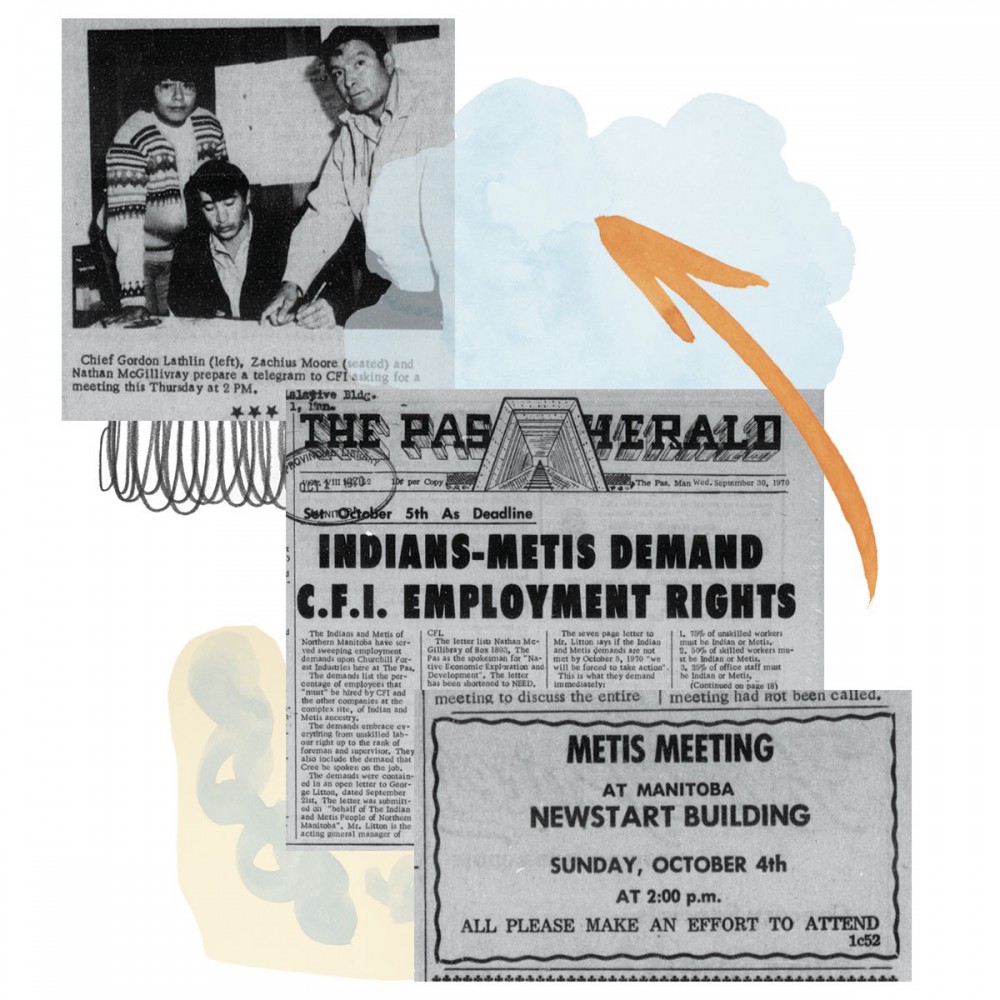

On September 21, 1970, a new organization, Native Economic Exploration and Development (NEED), telegrammed a seven-page letter to Litton’s New York offices. On “behalf of the Indian and Metis people of northern Manitoba,” NEED made several demands, including that within two years, 75 per cent of mill jobs and 50 per cent of office jobs at the complex go to First Nations and Métis workers; that on-the-job training be provided wherever necessary to meet these quotas; that all workers be adequately housed; that all forepersons and management speak fluent Cree; and that reliable transportation be provided to connect the complex to the white town, the OCN, Big Eddy, Umpherville, and Young’s Point. NEED organizers gestured at the possibility of solidarity between Indigenous workers and white workers, both of whom were being commanded by Monoca A.G. St. Moritz. In a mailout to the white town, a NEED pamphlet read: “We feel that it is our right to follow up CFI [Monoca A.G. St. Moritz’s local subsidiary] statements. Maybe the town people also have this right.… NEED feels that the town, CFI, Metis settlements, and Indian reserves must discuss the present development and the future of all these communities.”

NEED picketed the Forest Products Complex in October, 1970, after Litton ignored their telegram. They carried signs that read, “LAND AND PROSPERITY – FOR WHOM?”; “POVERTY – WHAT A HELL OF A PRICE TO PAY FOR PROGRESS AND CIVILIZATION”; and “WHY ARE YOU SO ANTI-INDIAN-METIS?” The action resulted in a meeting and vague assurances from Monoca A.G. St. Moritz officials, which Manitoba NDP Premier Ed Schreyer said were good enough for him. Editorials in the Pas Herald mocked NEED’s demands. Later, when Monoca A.G. St. Moritz claimed that it couldn’t hire Cree and Métis people because they lacked special training, and the company refused to provide that training, the NDP government set up a program to train Cree and Métis workers at Moose Lake, Manitoba. The program was underfunded from the start and enrolled just 34 workers, several of whom saw the writing on the wall and quickly dropped out.

Alvin estimates that if 5,000 people worked inside the mills of the Forest Products Complex over the decades, fewer than 200 were Indigenous workers. Of those 200, most worked in the sawmill, where the jobs were worse than at the more tech-heavy pulp and paper mill next door. I speak with William G. Lathlin, one of the very few Cree people who worked at the pulp and paper mill and the only Indigenous tradesperson there for most of his 17 years. Lathlin tells me that some OCN residents were hired at the complex in the late 1970s but that they were all fired or quit, and after that no more OCN residents were hired. The complex was rife with anti-Native racism, slurs, and physical assaults, Lathlin says. His white co-workers wouldn’t acknowledge him on the street. In 1987, after an injury, Lathlin was fired.

Alvin estimates that if 5,000 people worked inside the mills of the Forest Products Complex over the decades, fewer than 200 were Indigenous workers.

“Racism is about economy,” Doris Young tells me, “It’s an individual thing. It’s never about the collective. For us it’s all about the collective.” Cree customs of sharing, of mutual responsibility, and so forth, Alvin says, were looked down on by the white town. The largely white unions at the complex, Young tells me, never acted in solidarity with workers from OCN (and, perhaps not incidentally, almost never confronted the owners of the complex). Taking collective action, especially “militantly” to gain access to basic needs was portrayed – at least, in the pages of the Pas Herald – as something that “unreasonable” Indians did. Ukrainians and other Slavic peoples in The Pas had been subject to similar narratives and targeted for deportation, in the pre–Second World War years, for taking to the streets for jobs. Now their children appeared eager to scramble up the ladder, breezing past their fellow workers picketing at the mill gates.

Redevelopment of The Pas to accommodate Monoca A.G. St. Moritz was also racially structured. The Métis parts of town, lacking even the minimal protections that the OCN possessed as a recognized First Nation, bore the brunt of the changes. Annette Niven was born in 1954 and grew up in the Ballantyne Settlement, a close-knit and self-built Métis community within the 7th Street area of The Pas. Niven’s grandmother lived in the Dion Camp but moved to the Ballantyne Settlement as the town fathers restructured The Pas into two distinct sections: a wealthy area west of the CNR tracks and a working-class area east of the tracks. Sewer and water lines ended abruptly east of the tracks and the roads turned to gravel. “We were pushed to 7th Street,” Niven explains, and “[the former Dion Camp lands] ended up being the ‘cream of the crop’ people’s houses.” “Because we were Métis that’s how we were treated.”

Thick bush insulated the Ballantyne Settlement and the larger 7th Street area from the rest of the town. Niven’s father, like many men in the neighbourhood, was a railroader for CNR but the families lived off the land as well, keeping up an autonomous way of life in the bush around their homes. They trapped and hunted moose, deer, duck, geese, squirrels, rabbits, and prairie chickens. They harvested wild berries and mushrooms, raised chickens, planted vegetable gardens, and kept huskies in dog houses for their sleds. The bush around her home was Niven’s playground as a little girl, where she picked strawberries, built forts, and played with her dogs. The Ballantyne Settlement fostered Métis solidarity. When Manitoba Hydro flooded out the nearby Métis community of Pine Bluff in the 1960s, many displaced families took shelter in the Ballantyne Settlement. Later in life, Niven went to work for the Manitoba Métis Federation in The Pas.

The Métis parts of town, lacking even the minimal protections that the OCN possessed as a recognized First Nation, bore the brunt of the changes.

When Monoca A.G. St. Moritz came to town, it had The Pas sign a contract promising to clear land, survey, and provide services for 500 new residential lots to accommodate the mill workers it hoped to attract to the complex. Town planners chose the 7th Street area for the new housing, annexing 388 acres. They bulldozed the bush around Niven’s and her neighbours’ homes in the Ballantyne Settlement, paved the roads, put in water, sewer, and electricity lines, built a new sewage treatment facility, and expanded the water treatment plant to serve the new area. Monoca A.G. St. Moritz, along with Winnipeg real estate developers Underwood McLellan and Associates, put up “modern residential subdivisions”: striking cul-de-sacs of cookie-cutter bungalows, complete with picture windows and multi-car driveways, and big apartment complexes with balconies and landscaped grounds. The town outfitted the subdivisions with new schools for the mill workers’ children, a new community college specializing in the labour requirements of the complex (including English lessons for Swedish and Finnish workers), and the new town swimming pool and ice-skating arena. The mill workers’ subdivisions swamped the Ballantyne Settlement. The Métis families’ homes remained standing, but their hunting, trapping, and harvesting lands were lost and the character of the area was totally transformed. The Ballantyne Settlement ceased to exist as such. Even today it is not well remembered in The Pas.

Because Monoca A.G. St. Moritz refused to pay property taxes – Manitoba officials flew to The Pas one morning, ordered the town to sign a contract agreeing not to tax the company, and flew back to Winnipeg that afternoon – financing the infrastructure for what came to be known as “The Pas expansion” turned into a high-profile story. The Manitoba government found millions of dollars in provincial and federal money for the companies’ new subdivisions and gave the money a fancy title, “The Pas Special Area Agreement.” To justify the big spending, they presented it as a modernization program for a zone much larger than the area they actually intended to invest in.

In the neighbourhoods where The Pas Métis Council had been organizing for several years for updated housing and infrastructure, the Special Area Agreement may have looked like a potential breakthrough. The OCN had been looped into the deal and had secured just under $2 million for their own infrastructure upgrades. In April 1970, John Fidler, John Samuel Lathlin, and John Robert Buck sent a telegram to the federal Department of Regional Economic Expansion that read: “We question rational leaving out Metis Settlements Big Eddy, Young’s Point, Umperville, adjacent The Pas, from total area Development scheme. We refuse forced relocation or forced integration. We request to be part of total development.” The blatant neglect of their communities, Métis people in The Pas implied, amounted to state-enforced displacement and loss of their distinct, historic communities. In a letter to the provincial and federal governments sent a month later, the leaders elaborated: “It may be asked, and some policy makers have already asked the question and have tried to give the answer, would it not be more reasonable for all the people in our communities to move into the town of The Pas, where water, sewers, fire protection, and many other services would be more readily available? We are the first to realize that some of our people may prefer to relocate into town. We rejoice that they have this free choice. But some of us, and the majority we speak for, prefer to stay where we are. Why, you may ask? Well, just because it is more like home.[…] Reason must indeed take into account the feelings as well.” Defiantly insisting that their communities deserved a future, the residents of Young’s Point, Umpherville, and Big Eddy rolled out a plan to guarantee it.

“We question rational leaving out Metis Settlements Big Eddy, Young’s Point, Umperville, adjacent The Pas, from total area Development scheme. We refuse forced relocation or forced integration. We request to be part of total development.”

First, they would compel Canada to acknowledge, in no uncertain terms, their legal right to the land under their homes. “We always remain fearful,” they wrote, “that some greedy land speculator will move in, and that we will be forced to move out, or to live on the fringe of our communities.” They called for a land tenure arrangement then being hatched in Umpherville to immediately be extended to Big Eddy and to Young’s Point as well. This would guarantee that any new housing, sewer, water, or electricity lines built in their communities would be for them, not for a scheme that would displace or swamp them. Second, they proposed a special model of development that would foster people’s skills, confidence, and connection to the community while it would improve living standards. They proposed to expand a one-year initiative recently won from the Manitoba government, through which local people had built 10 houses while learning all the necessary construction skills. “The appeal,” they wrote, is “for training where theory and practice are blended together with concrete results.” Construction would take longer, they acknowledged, but the long-term benefits would be worth it.

A 1969 Special Area Agreement planning directive stated that “[a]ll development of an urban nature that can be accommodated within the Town of The Pas, should be located in The Pas.” In effect, it was an instruction forbidding the use of the agreement’s funds to improve the Métis parts of town. For years, the Manitoba government had studied Métis so-called fringe communities and pondered ways to get rid of them. Their residents’ “unwillingness to relocate to areas of employment” was considered a significant stumbling block to the modernization of the North. Canada’s 20th-century fantasy that Métis communities would disappear through out-migration and “integration” resulted in actions designed to starve them out of existence. In the end, little to none of the $145 million (in 2019 dollars) invested in The Pas expansion went to Big Eddy, Umpherville, or Young’s Point. The agreement was designed not to strengthen the area’s existing communities but to meet Monoca A.G. St. Moritz’s specific requirements for mill-worker housing and for “a good residential atmosphere” capable of attracting non-Native management and engineers to The Pas.

A decade earlier, in 1957, in the midst of the country’s postwar boom, the Finger mill closed, and 400 residents of The Pas lost their jobs. “A few years ago,” the Winnipeg Free Press reported in 1970, “this mid-northern community was in many respects a large collective slum of 5,000 persons which had been heading steadily downhill.” A sense of anxiety comes through, in the Free Press’s articles about the complex in The Pas, about the wider economic good times that Manitoba, perhaps, was not enjoying as much as it could be. So many state activities – planning the pulp and power economy, building hydro dams, subsidizing Monoca A.G. St. Moritz, orchestrating the Special Area Agreement – were designed, it seems, to achieve a level of postwar prosperity to which Manitobans understood themselves to be entitled. The refurbished town of The Pas was supposed to be the culmination of all this. “In the town itself new homes, apartment blocks and busy stores give evidence of the much-needed weekly pay packets handed to men working on [the new mill],” the Free Press reported. “The town has dressed itself up and stepped out,” said one Special Area Agreement official. The history of The Pas points to the possibility that this epoch of upward mobility, of stepping out and on to the stage of postwar prosperity, was purchased at the direct expense of Cree and Métis people. The idea that Monoca A.G. St. Moritz would save The Pas from its racial order was a ploy. In fact, the opposite occurred: the firm turned the racial order in The Pas to its advantage, reactivated it, baked it into the town’s postwar boom and into the new identities emerging from it. Manitoba officials after 1966 had a tendency to refer to The Pas as the province’s “last great frontier,” a place with “the zest” of a “frontier town.” A poem by Bert Huffman, “The Northland,” became a favourite quote in 1960s The Pas Chamber of Commerce publications: “Northward, northward, turn your vision / To a land that’s fresh and braw … Hit the trail, canoe and portage / Feel yourself become a man.”

Arguably the most infamous event in the history of The Pas took place on November 13, 1971. The town was riding high, approaching one of the biggest crests of the Forest Products Complex boom. The complex’s sawmill entered production that year and the new 7th Street subdivisions were rounding into form. A thousand people had moved to the town in the previous five years. On almost every corner a new bank, store, or motel was going up. On November 18, 1971, 500 people would gather to watch Mayor Harry Trager cut the ribbon on the town’s first indoor shopping mall, on Edwards Avenue. “We’re going to be an empire by ourselves here in the north,” Trager said that morning, “an empire that all of Canada can be proud of.” Just five days earlier, 19-year-old Helen Betty Osborne, a young Cree woman originally from Norway House First Nation, then a student at Margaret Barbour Collegiate Institute in The Pas, was murdered by four white men from The Pas.

Despite knowledge of the four men involved in the murder, local RCMP failed to press charges and abandoned their investigation a year later. It eventually emerged that it was widely known, among the white townspeople of The Pas, exactly who had killed Osborne, and that a collective effort was being made to protect the killers. Twelve years passed before the RCMP reopened the case and brought charges against the men, only one of whom was convicted in 1987. Osborne became a touchstone in struggles for police accountability and for justice for missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, thanks to the determination of Cree activists that resulted in the 1988–91 Aboriginal Justice Inquiry of Manitoba (AJI) and a 1989 book by journalist Lisa Priest, Conspiracy of Silence, that became a CBC television miniseries.

It eventually emerged that it was widely known, among the white townspeople of The Pas, exactly who had killed Osborne, and that a collective effort was being made to protect the killers.

Most attempts to make sense of Osborne’s murder have zeroed in on the place where it occurred and concluded that something about The Pas itself was to blame. A popular story is that The Pas has always been a rough-and-tumble kind of place – a scrappy, colourful, unrefined, off-the-beaten track, northern frontier town. The boom of 1971, the story goes, exacerbated this characteristic, attracting hundreds of young, single, hard-working men, putting money in their pockets, and allowing them to blow off steam, sometimes to excess. This story – one that Priest wrote and that several white townspeople, especially men, have told me – usually allows the teller to gloss over the forces of racism and misogyny entirely. Another popular story – one that the AJI told and one that is far more to the point – is that The Pas in 1971 was a town divided. Racial segregation at the Lido and the Gateway, as well as the frequent assaults, with impunity, on Cree people, this story goes, are ample evidence of a long-standing racial order at The Pas that authorized anti-Native violence.

The latter story is certainly true. But could it be usefully elaborated by thinking about how, specifically, The Pas was changing in the late 1960s and early 1970s and about how the racial order had become newly profitable? What happens when we widen the frame around our picture of The Pas in 1971 to include the Cree workers picketing at the mill gates, the urgent telegrams written by The Pas Métis Council, and the bulldozers erasing Niven’s childhood playground and his family’s source of sustenance? We see, at least, that a certain mix of white masculinity and Indigenous subordination was key to the labour hierarchy at the mill, that divestment from Indigenous lives was the modus operandi of the mill’s urban improvement schemes, and that the province’s “pulp and power” future positioned young Indigenous women as disposable obstacles to, rather than the rightful bearers of, Manitoba’s future.

Osborne’s murder accelerated the OCN’s self-determination agenda. Students from the OCN largely stopped attending Margaret Barbour, Young tells me. “Integration” was short-lived, if it could be said to have taken place at all. Some in The Pas who remember those days recognize them as an abject failure. “Integrated schools didn’t work out very good,” Harvey acknowledges. “They expected the kids to solve the problems their parents had.” Spurned at the gates of the Forest Products Complex, the OCN concocted its own plan: they would build, own, and operate a much bigger, flashier indoor shopping mall than the one on Edwards Avenue, capture some of the mill workers’ pay via retail, and create jobs for themselves that way. Despite intense resistance by The Pas’s merchant class, who, fearing the competition, begged the Department of Indian Affairs in Ottawa to stop the OCN from building it, the grand opening of the Otineka Mall was held in the OCN in October 1976.

On January 11, 1971, Monoca A.G. St. Moritz, Technopulp Inc., and the other affiliated firms at the complex went into receivership. The government loans, amounting to about $600 million (in 2019 dollars), were never repaid. It was later revealed that $289 million (in 2019 dollars), or almost half, of this amount never actually went into the construction of the mills but was, instead, billed as “fees” and absconded with by Monoca A.G. St. Moritz, Technopulp Inc., and their other affiliates. The actual owners of the companies remained officially anonymous, as per the original agreement. After extensive research, Financial Post assistant editor Philip Mathias published evidence, in a 1971 book, that Monoca A.G. St. Moritz and the other firms at the complex “were part of a string of between 20 and 200 companies connected by interlocking directorships,” many of them shell companies, and they were, in fact, “an instrument for the Sindona group,” a millionaire clique led by Sicilian financier Michele Sindona.

It was later revealed that $289 million (in 2019 dollars), or almost half, of this amount never actually went into the construction of the mills but was, instead, billed as “fees” and absconded with by Monoca A.G. St. Moritz, Technopulp Inc., and their other affiliates.

One of the richest men in Italy and a major political figure since befriending Pope Paul VI in 1962, Sindona was well known as a staunch opponent of the Italian Communist Party and a bankroller of Italy’s ruling Christian Democratic Party. In 1967, the Manitoba government told the Financial Post that Sindona was “the man behind the complex” at The Pas, a claim that Sindona vehemently denied in a hand-delivered letter to the Financial Post’s Montreal offices. Mathias backed up his claim by reporting, among other things, that in early 1966 Monoca A.G. St. Moritz officials took Manitoba Premier Duff Roblin on a tour of “the Siace mill,” a state-of-the-art complex of eucalyptus groves and cardboard mills in Sicily, where Sindona was on the board of directors; that ministers of the Sicilian Regional Assembly travelled to Winnipeg to express support for the deal shortly before it was signed; and that Siace board members inexplicably appeared in photographs beside Roblin and Monoca A.G. St. Moritz representatives at the signing of the agreement in Geneva. In 1980, while Sindona was imprisoned for fraud in Otisville, New York, New York Magazine reported that Sindona was linked to the New Jersey-based Gambino crime family and had spent millions bribing public officials around the world over the past 15 years. In 1986, while serving a life sentence in a Voghera, Italy, prison for contracting the assassination of a lawyer, Sindona’s coffee was poisoned with cyanide and he passed away. In its March 23, 1986 obituary, the New York Times described Sindona as a “master swindler” responsible for, among other things, the 1974 failure of Franklin National Bank, “the largest bank collapse in United States history” at the time. While these details of Sindona’s exploits emerged in the 1980s, his connection to The Pas has not been re-examined.

The massive fraud at The Pas is a modest entry in the annals of Canadian racial capitalism. In light of the history of Cree and Métis political action, it could be said that a quarter-billion dollars were stolen out of the mouths of children, from over the heads of families, from people seeking meaningful work in the prime of life. The so-called costs of justice for NEED and The Pas Métis Council appear even more reasonable when, put in proper context, they are contrasted with the actual siphoning of hundreds of millions of dollars into Swiss bank accounts. It was Manitoba officials’ stubborn drive to hand resources over to capitalists – and their capacity to create corresponding structures such as the Manitoba Development Fund – that took opportunities away from everyday people and handed them over to the Sindonas of the world. Interestingly, those precise institutional forms, which at times have been identified as key precursors to the neoliberal turn in Manitoba, were pushed on Manitoba by consultants with direct ties to a network of firms and financiers concertedly aiming to steal from governments around the world.

After Monoca A.G. St. Moritz disappeared, the Manitoba government took over the mills at the Forest Products Complex and operated them via a new Crown corporation called Manfor. In doing so, Manitoba recouped $319 million (in 2019 dollars) of its investment in the complex. In 1989, it sold the mills to Repap Enterprises for $240 million (in 2019 dollars), an effective loss of $79 million (in 2019 dollars). The Forest Products Complex now operates as a shell of its former self, employing about 300 people, regularly changing owners, and threatening to close for good. Meanwhile, young Cree and Métis people in the OCN band office, the Manitoba Métis Federation office, the University College of the North campus, and in the streets, are busy writing the town’s next chapter.