Clutching a mug of coffee, Gwenda Yuzicappi retreats from the cold outside. There’s a spark in her eyes. Her long brown hair is pulled back, and the pink sweater she wears complements the flush in her cheeks from the biting winter wind. Her younger sister sits beside her in the coffee shop and they speak animatedly. If you watched long enough you could find the grief that Yuzicappi carries, but in this moment she looks hopeful.

Yuzicappi spent the day with other families like hers, those with missing or murdered daughters and sisters. She told them about Amber Redman, her daughter, and then she listened as they spoke of their loved ones. The family members of Saskatchewan’s missing women had come together to share their stories and remind each other that they aren’t alone, and that together they aren’t powerless.

Sharing the pain helps but brings its own devastation. The Saskatchewan Association of Chiefs of Police website lists 30 cases involving missing women. More than half of those are of aboriginal descent. Some date as far back as the early 1930s.

Myrna Montgrand was 14 when she was last seen at a party in 1964.

Shirley Joanne Lonethunder went missing in downtown Saskatoon. It was Christmas Eve, 1991. She was 25.

Daleen Kay Bosse had been at a conference with colleagues. They’d stopped for a drink at a local club in Saskatoon. Her car was recovered, but three and half years later there has been no sign of the 25-year-old mother.

Others, like Melanie Geddes, have been found dead. Their missing person investigations have become homicide cases. Unsolved cases of missing and murdered women across Canada number in the hundreds, according to ongoing research by Amnesty International and the Native Women’s Association of Canada. Government statistics show young indigenous women are five times more likely than all other women to die as a result of violence.

Last year a provincial task force was formed in Saskatchewan. This task force is behind the meeting that brought these families together. Yuzicappi believes families should have had input sooner, but she’s still glad for the opportunity to have a day, face-to-face, with people who can provide some answers to the nagging questions they share.

Questions like, When is a case considered “cold”?

Do you inform the families of this status?

Our sister has been missing for 14 years; can we submit a new report?

What can we do that we aren’t already doing?

Canadian Government statistics show young indigenous women are five times more likely than all other women to die as a result of violence.

Yuzicappi fights to keep her daughter’s spirit alive. Earlier in the week she organized a winter feast at Standing Buffalo First Nation in honour of her daughter’s birthday.

Amber Redman was 19 when she disappeared. It was the early hours of July 15, 2005. It had been a warm summer night. Yuzicappi imagined Amber was out with her girlfriends, dancing to country music under the stars at Craven’s annual Big Valley Jamboree. She imagined a night of carefree fun for her beautiful daughter, who had just graduated from high school and had her whole life ahead of her.

Amber never came home that night. Her boyfriend called Yuzicappi worried the next day. They had had a fight and he hadn’t heard from her. Amber was last seen at around 2:30 am outside the Trapper’s Bar in Fort Qu’Appelle, Saskatchewan.

Eighteen months later her mother knows little more about the circumstances of her disappearance, but she keeps talking, and keeps asking questions.

“The more I talk the more I keep Amber’s spirit alive. This is my purpose—letting one more person know she is still missing.”

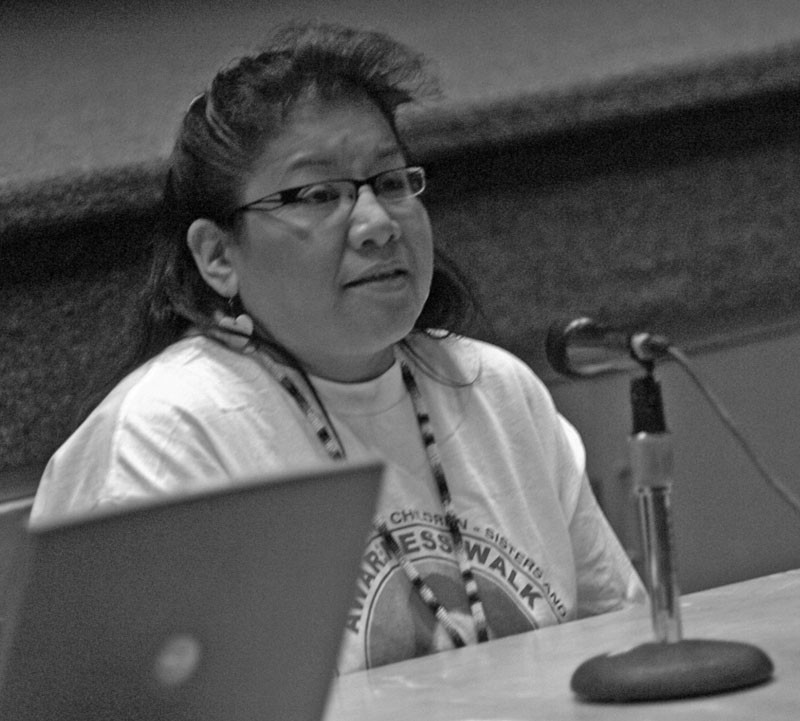

Yuzicappi speaks at schools, at conferences, and, last fall, at Missing and Taken, a symposium organized by the Dunlop Art Gallery and the Department of Women’s Studies at the University of Regina.

That’s where she and filmmaker Lourdes Portillo first met. Yuzicappi was part of a panel discussion, and relayed her daughter’s story to the small audience. Portillo sat forward in her theatre chair, taking in Yuzicappi’s all-too-familiar story.

Portillo is an acclaimed Chicana filmmaker. One of her most highly praised and haunting works is the documentary Señorita Extraviada (Missing Young Woman), about the serial disappearances and murders of women in the border city of Juárez, Mexico. Portillo has spent many years researching the situations that allow for these unsolved crimes against so many indigenous women around the world. Along the way mothers just like Yuzicappi have become her close friends.

Portillo’s film was screened the first night of the symposium. Afterwards, most people were left silent, heavy in their seats. Portillo had taken great care not to revictimize the women or their families with gruesome images, but the eerie documentation of the hundreds of young indigenous women who have been kidnapped, raped and brutally murdered in Juárez, created a collective shudder.

The murders began in 1993. They continue to this day. According to Amnesty International, almost 400 women and girls have been murdered, and more than 70 remain missing.

Portillo says it was the lack of media attention that drew her to the story.

“I started seeing small articles in the Mexican newspaper about girls gone missing. At least 50 girls had gone missing, and the numbers kept on increasing. But the articles were so small and so insignificant.”

Portillo had a hard time getting information from authorities in the infamously corrupt border city, so she turned to those who most needed answers. With her video camera in tow she followed families as they lobbied the government, painted pink crosses all over the city and protested in city squares. Some progress has been made, but not nearly enough. And the killings continue.

“It’s not just in Juárez where girls have gone missing in this very serial-killing-kind-of-way,” says Portillo.

Thousands of indigenous women have been killed in Guatemala as well. “It’s happening all over the Americas. That is partly the reason I am here in Canada, because I see the same thing has happened here.”

Portillo believes that the victims are overwhelmingly indigenous women and girls because, in a racist and sexist society, these women make easy targets. “We are almost not seen as human beings, so it is easy to kill indigenous women and get rid of them. No one will protest.

“They are poor, they are indigenous, they are unprotected and sometimes they are prostitutes so if you kill them—so what?”

But Portillo sees things starting to change, as families of the victims organize to fight these crimes. She sees it happening in Mexico, and here in Canada, too. She’s hoping her film and the work of these families around the globe force people to realize the magnitude of these crimes.

“Someone is getting away with a lot of murders. Who are these men who are doing this? We have to talk about it; we have to let people know about it and demand justice and demand investigations and results. It’s really hard to believe that in Canada there have been so many murders and so many of them are unsolved.”

This has been Portillo’s hope: that these mothers, who live worlds apart and yet share so much pain, can be buoyed by the connections they make.

Yuzicappi doesn’t know what happened to Amber. She fears Portillo could be right about the parallels with Juárez. Last fall she saw a missing person poster for Marie Lynn Lasas. The 19-year-old also disappeared close to home and without a trace. Her photo resembled Amber’s so much that Yuzicappi did a double-take.

She is trying to stay hopeful, however. She has to. As she met families of other missing girls at the task force gathering, she realized that things are changing, even if it is slowly. Sitting next to her was the family of Joyce Tilloston, who disappeared November 14, 1993. She was last seen leaving her Regina home to visit a friend. Tilloston’s family told Yuzicappi how hard it was to get the police to pay attention. The meeting was one of the first times they’ve had the support of others who know their pain.

Yuzicappi will continue to reach out, inviting families and media to the seasonal walks and feasts she holds. She knows that in some small way it’s making a difference to her daughter and many other women who have vanished.

In February Yuzicappi and other mothers and fathers travelled to Vancouver, where people just like them are enduring the horrific details of Robert Pickton’s high-profile murder trial.

“I’ve been in touch with some of the families,” said Yuzicappi shortly before departing. “They said the first day the courtroom was packed with people: media, supporters, extended family and friends. After the second day there were far fewer. It’s not making top story anymore. They feel abandoned again.”

Yuzicappi is also planning to meet with Portillo again. They will both be speaking at a symposium in San Francisco this May. Yuzicappi will represent Canada on a panel with two other mothers—one from Guatemala and the other from Argentina.

This has been Portillo’s hope: that these mothers, who live worlds apart and yet share so much pain, can be buoyed by the connections they make. These connections keep Yuzicappi focused, helping her to go on searching for her daughter.

“I have a lot of hope that there will be a break in this case and we will find her. I will continue to believe she is alive until I have the facts that she is gone.”

Brett Bradshaw is a freelance journalist whose work often focuses on women’s rights and health, First Nations and immigrant communities, and arts and culture.