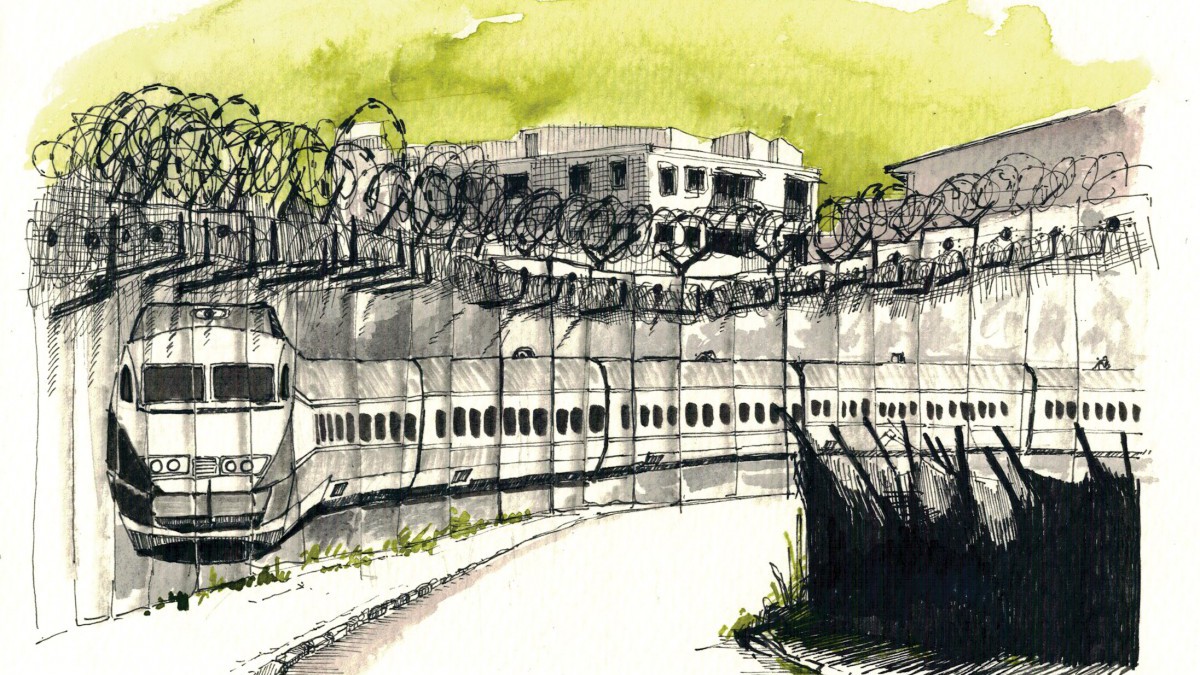

In two small Palestinian villages in the West Bank – Beit Iksa and Beit Sourik – residents have struggled against Israeli occupation and annexation of their land for many years. While the Israeli state has historically confiscated land around these villages to build illegal settlements and the separation wall, the most recent land seizures are for a different purpose – the construction of a high-speed rail line connecting Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, promising to move travellers over the 56 kilometres between the cities in 28 minutes flat. The route passes through the occupied West Bank in two places and crosses the Green Line – the demarcation line between Israel and its neighbours that was negotiated after the 1948 Arab–Israeli war and held until 1967.

The Beit Sourik Village Council emphatically states: “We, the people of Beit Surik, do not want the train line to be built on our land. We see as fundamentally important that the people of the world support our right to decide on the use of our own land and help us change the route of this train line.” Despite these demands from Palestinians, the proposed train route has remained unchanged, and construction is proceeding as planned.

If you have not heard of these villages, or the A1 rail line in question, you are not alone. Mainstream media in Canada tends to mute dissenting Palestinian voices from villages like Beit Iksa and Beit Sourik, despite the gravity of the situation they face. But the decidedly Canadian connection to this case cannot be ignored. Within one of the most deeply contested geographic spaces on the planet, aerospace giant Bombardier, with the support of the Canadian state, is supplying Israel with the trains that will run on the high-speed line upon completion. In the face of mounting evidence of the illegality of this project under international law, a long history of dispossession and colonialism for Palestinians, and the growing Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement against Israel, Bombardier has established a long-term presence in Israel.

A leg up for Bombardier

Bombardier is one of the world’s largest global transportation companies, with revenues of $18.2 billion in the 2015 fiscal year. Headquartered in Montreal, and with shares traded on the Toronto Stock Exchange, Bombardier is a global giant in its two core business divisions: aerospace and rail transportation. It employs almost 71,000 people in more than 28 countries.

The Canadian state has played an important role in encouraging and supporting the success of Bombardier over the decades. Bombardier itself boasts that the government, through the Technology Partnerships Canada program, has invested $142 million in the company’s research and development. Export Development Canada (EDC), Canada’s export credit agency, has also invested heavily in Bombardier, helping it to secure lucrative contracts abroad and providing financing to foreign companies to purchase products and services from Bombardier. The Canada Account, which finances transactions that EDC deems too risky but are still considered to be in the national interest, has dispensed financing at least five times in the past 15 years to support the sale of Bombardier aircraft.

Canadians are also both helping to finance, and profiting from, the work of Bombardier. Many Canadians own Bombardier shares, either through private investments or managed pension funds. As of March 2016, the Canada Pension Plan owned $11 million in Bombardier shares.

Bombardier in Israel

Bombardier began its relationship with the Israeli state and Israel Railways Corporation Ltd. – the state-owned rail corporation that provides passenger and cargo transport – in the late 1990s. Shortly after the Canada-Israel Free Trade Agreement was signed in 1996, executives from Bombardier accompanied dozens of other corporate representatives, Canadian politicians, and Jewish lobby groups on a trade mission to Israel. A second trade mission organized by the Canadian government followed in February 1999, which included two senior sales executives from Bombardier. The efforts of the Canadian state and Bombardier to enter the Israeli rail market began to bear fruit very quickly. In the summer of 1999, the company received its first contract with Israel Railways to deliver four double-deck train sets. In the intervening years, Bombardier emerged as a major supplier of double-decker coaches for the transit system in and around Tel Aviv. The company has secured several contracts with Israel Railways since 1999, including the most recent deal in 2015, worth $340 million, to supply 62 electric locomotives, with an option for another 32 locomotives in the future.

A1 and international law

Initially scheduled for completion by 2008, the A1 rail line is now planned to officially open in 2018. The train route crosses into the occupied territory of the West Bank in two spots: first, the path dips into the West Bank in order to create the most direct route between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, and second, it crosses the Green Line to accommodate Israeli citizens who opposed its construction close to their homes. In total, the rail line runs for roughly six kilometres across the Green Line into occupied territory, though most Palestinians living in the occupied territories won’t be able to use the train given Palestinians’ restricted mobility rights in the areas at the ends of the line.

The fact that the train crosses into occupied territory raises significant legal concerns regarding the construction of the A1, most importantly regarding Israel’s commitments under the Fourth Geneva Convention, which was adopted in 1949 and signed by 196 states. The convention outlines humanitarian protections for civilians in a war zone, including the rights of people under occupation. Of these, the most relevant sections for this case are articles 47 and 53. Article 47 notes that people under occupation cannot be deprived of their rights under the convention due to the annexation of land by the occupying power. Article 53 prohibits the destruction of property by the occupying power, “except where such destruction is rendered absolutely necessary by military operations.” The annexation and subsequent destruction of land to build the A1 rail line in occupied territory arguably constitutes a violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention.

In addition to Israel’s responsibilities as an occupying power under the convention, the United Nations’ Charter, General Assembly Resolution 2625, Security Council Resolution 242, and the International Court of Justice (ICJ)’s 2004 Advisory Opinion on the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, all prohibit the acquisition of territory by force and uphold the self-determination of peoples. But the problem with international law is that it is rarely enforced against powerful actors, especially in this case, where the most powerful state in the world, the U.S., backs Israel.

It should be noted that the Israeli state takes the position that the rules and principles of the Fourth Geneva Convention, along with other aspects of international humanitarian law and human rights law, should not apply to the occupied Palestinian territories. This view is founded on the idea that the territories in question were not previously recognized as part of a sovereign state. This position was contested most clearly by the 2004 advisory opinion of the ICJ, when it ruled on the illegality of Israel’s separation wall.

A report written by a Palestinian organization, the BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights, summarizes the legal concerns with the rail line as follows: “In blatant violation of its obligations under international humanitarian and human rights law, Israel as the occupying power has, without military necessity, expropriated privately owned Palestinian land with the aim of constructing permanent infrastructure, ostensibly to serve the needs of its own civilian population.”

The new A1 infrastructure is situated within historical and contemporary processes of dispossession in the region. After a long process of building the Zionist movement, the colonial project reached a critical point with what Palestinians refer to as the Nakba (“catastrophe”), when over 700,000 Palestinian Arabs were expelled from (or fled) the land in 1948–1949, during the formation of the Israeli state. After the Six-Day War in 1967, Israel began its occupation of several other territories in the region, including the West Bank. Since then, the Israeli state has gradually expropriated an increasing amount of the West Bank land to build settlements, checkpoints, and the separation wall. Abu Shadi, the head of the local council of Beit Iksa, says, “[T]he checkpoint, the fence, settlement expansion on our lands, settler attacks, soldiers in the valley. The train is just one part of it all.”

Although the total distance of the rail line running through occupied territory is minimal – roughly six kilometres – Palestinians in the area assert that it will cause damages and obstruct their self-determination. In a letter calling for international support and intervention in 2010, the Village Council of Beit Sourik argues, “This train line would bring inconvenience and suffering to the village in terms of the lost land and in noise pollution, without any benefits, as the train is to connect areas that village residents, with West Bank ID cards, are not allowed to enter.” Beyond the immediate and direct consequences of the rail line for Palestinians in the region, there is an equally important matter of principle regarding the annexation of these small pieces of land. Each small incursion and seizure contributes to a much larger picture of dispossession.

Up against BDS

Bombardier is quick to dismiss any suggestion that its work in Israel is problematic. Asked by a reporter for Mamon, a sister publication of Ynetnews, about the significance of the railway going beyond the Green Line into occupied territory, Dr. Lutz Bertling, former head of Bombardier’s transportation division, replied, “This is not a problem. What do we provide? Railway systems to all residents, no matter their nationality. There is no apartheid in Israel. Eventually, everyone stands to gain from a good and effective railway, in any area it passes through. As far as we’re concerned there is a green light to participate in all bids in Israel, even in upcoming bids over the Jerusalem light rail. It’s not in our DNA to deal with political issues.”

Bombardier elides any notion that its work in Israel might have political, legal, or ethical complications, but of course, its operations are political. In fact, it is firmly nested within the context of the growing BDS movement directed at the state of Israel. BDS, in its own words, “works to end international support for Israel’s oppression of Palestinians and pressure Israel to comply with international law.” The movement was launched in 2005 by roughly 170 Palestinian civil society organizations as a non-violent mechanism to put pressure on the state of Israel. It is a call for assistance from the international community to boycott Israel’s economic projects, and the academic, cultural, and sporting institutions that are complicit in the violation of Palestinian human rights; to withdraw investments in Israeli companies and international companies involved in Israel; and to pressure all governments and international governance bodies to end governance, military, and trade co-operation with Israel until Israel complies with international law.

In 2010, the Palestinian BDS National Committee unequivocally stated that the A1 rail project violates international and human rights laws. It urged “private businesses to immediately withdraw from the project.” Activists in Germany and Italy picked up the call: the Italian coalition Stop That Train campaigned against the participation of their national firms that were involved with the project. Although the Italian firm Pizzarotti has continued its work on the project, a subsidiary of German state-owned firm Deutsche Bahn withdrew from the A1 rail line in 2011. Former German transport minister Peter Ramsauer announced at the time, “this Israeli railway project which runs through occupied territory is problematic from a foreign policy standpoint and is potentially against international law.”

For its part, Bombardier is just now beginning to encounter civil society opposition in Canada to its participation in the A1 line. In late 2015, Independent Jewish Voices (IJV) Canada, a national Jewish organization that calls on the Israeli government to comply with international law, posted a letter to Bombardier on its website publicly criticizing the company’s president for his blasé response. It read, “I am disturbed to have read that Dr. Lutz Bertling of Bombardier stated that he has no problem with Israeli trains going beyond the Green Line, the internationally-recognized [sic] border of Israel.”

Fortunately for Bombardier, Canadian governments appear openly hostile to the BDS movement. In January 2015, John Baird, Conservative foreign affairs minister at the time, issued a press release after his meeting with his Israeli counterpart, which read: “Canada will fight any efforts internationally to delegitimize the State of Israel, including the disturbing Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) Movement.”

The Liberals do not appear to have altered the Canadian government’s position on BDS. In February 2016, almost all Liberal MPs voted in favour of a Conservative motion condemning the BDS movement against Israel.

Shared complicity and the way forward

The legal and ethical implications of Bombardier’s involvement in Palestinian territories extend beyond the scope of Bombardier itself, falling upon both the Canadian government and Canadian citizens at large. Global Affairs Canada’s position that the Fourth Geneva Convention applies to the occupied Palestinian territories is inconsistent with Bombardier’s work in supplying trains for the A1 high-speed line. The various ways in which Canadians finance, and profit from, the activities of Bombardier overseas should provide reason for further scrutiny of this case.

In an interview with The Intercept’s Glenn Greenwald, BDS co-founder Omar Barghouti noted, “Many people are realizing that Israel is a regime of occupation, settler colonialism, and apartheid and are therefore taking action to hold it to account to international law. Israel is realizing that companies are abandoning their projects in Israel that violate international law, pension funds are doing the same, major artists are refusing to play Tel Aviv.”

As the BDS movement grows internationally, Canadians can and should play an important role in challenging the Canadian state and corporations like Bombardier. National organizations, such as Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East, IJV Canada, and the Canadian BDS Coalition, along with many other, more localized movements across the country, are already mobilizing Canadians to join the BDS movement.

This activism is crucial in light of the Canadian government’s unwavering support for the Israeli state. According to Palestinian-Canadian activist and artist Rafeef Ziadah, “Unlike the endless rounds of negotiations, BDS does not rely on the delusional belief in the goodwill of Western governments… As Israel’s actions continue unabated, the task of building a capacity for pressure is more urgent than ever.” The Bombardier case must be leveraged to interrogate the Canadian connections to this particular project, while also drawing our attention to what activists are doing to address the broader problems in the region.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)