A few short weeks after his speech at a Regina campus, Fred Hampton was assassinated in his home by Chicago police.

While the visit of the deputy chairman of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party (BPP) left its mark on Regina in 1969, over 50 years later, his memory was mobilized by brothers Tiro and Thabo Mthembu through their Black-owned restaurant and gathering space, the Hampton Hub.

Tiro explains it was an opportunity for him and Thabo to assert an alternative narrative to that of Saskatchewan’s right-wing political landscape. Regina is often referred to as the “Queen City,” and noting the abundance of bars named after colonial figures, Tiro says, “We live in a place where we celebrate British monarchy on a very absurd and disgusting level […] So [there was] a need to uplift heroes of ours – Fred Hampton was one of my heroes.” As Tiro explains, the brothers wanted to “encourage [the local Black] community to recognize that, yes, under this current neo-fascist regime it can feel like we don't have any deep, progressive roots. But these prairies are built on fighting oppression.”

So, in 2022, the vegan restaurant opened in Regina’s Heritage neighbourhood. In an industry dominated by white restaurant ownership, the Hampton Hub was a site of Black agency and autonomy. The brothers created “a space that is ours,” Thabo proudly recalls.

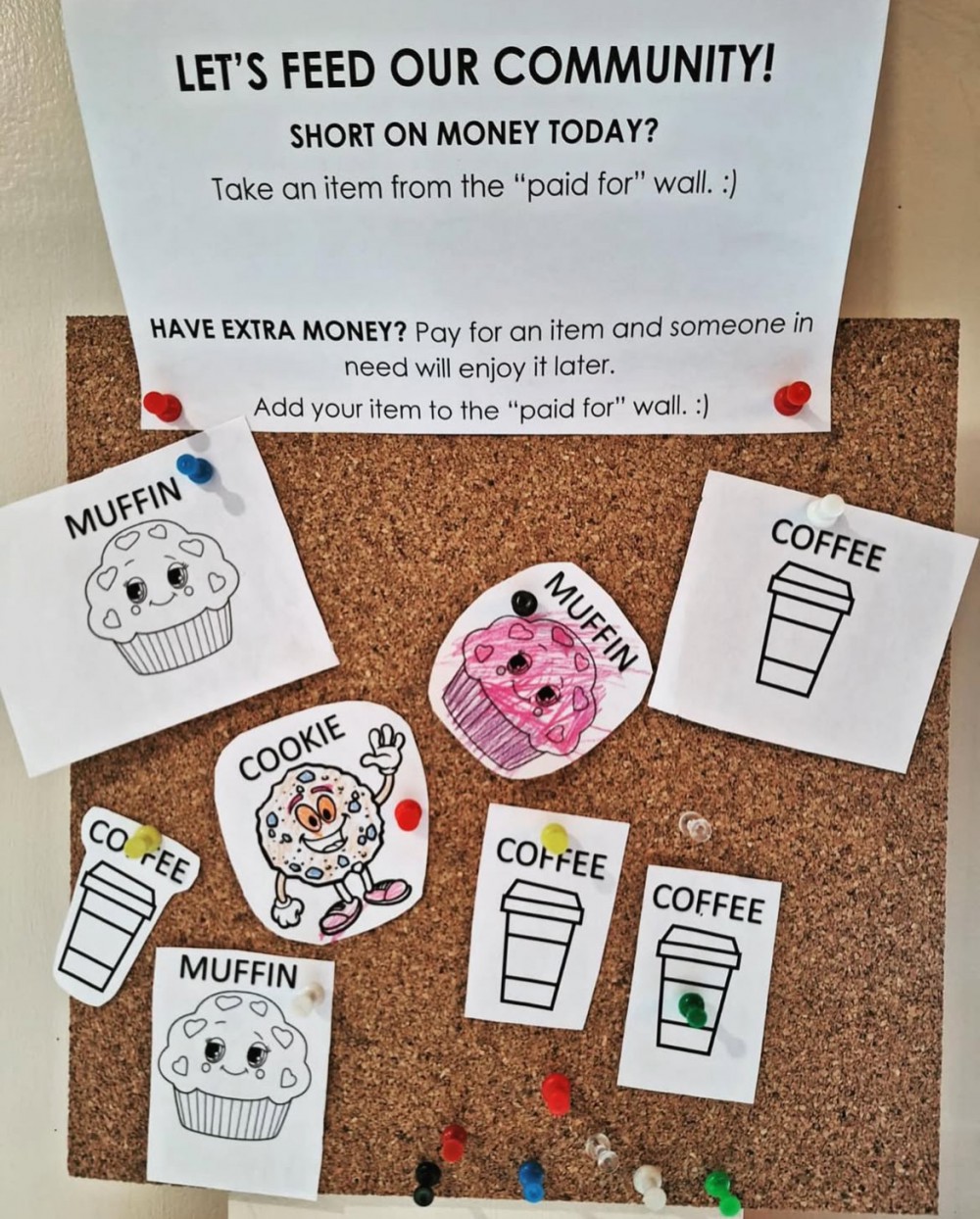

“When you starve people,” he says, “you create food scarcity and food insecurity; you create communities very vulnerable to oppression. So, my philosophy of food is [that] the most revolutionary thing we can do is fight for food sovereignty and address food insecurity [through] solidarity.”

The Hampton Hub’s community food board.

Feeding the Revolution

In particular, Fred Hampton’s “rainbow coalition,” a collective of racialized Black, brown and white working- and under- class people, and the Black Panther Party’s “survival programs,” offered a model and vision to apply to Treaty 4 territory. Using the Hampton Hub as a physical base and Fred Hampton’s political praxis as a guiding ideology, the Mthembu brothers engaged in community organizing grounded in the history of settler colonialism in the “Queen City.”

Across the Prairies, starvation has been wielded as a colonial weapon against Indigenous Peoples. In addition to the colonial government’s calculated extermination of millions of bison, figures such as Edgar Dewdney – the lieutenant governor and Indian commissioner of the North-West Territories, which included what is now modern-day Saskatchewan – withheld rations to force Indigenous people onto reserves to make way for white settlement.

“Dewdney was so strategic,” Tiro says. “[He knew] you couldn't starve people to the point where they die, but if you starve people to a certain level, you get a lot done out of them, right?”

Making connections between Treaty 4, Hitler’s Germany, occupied Palestine, and apartheid South Africa, Tiro explains that tactics of starvation are part of the playbook of colonial and fascist regimes. “When you starve people,” he says, “you create food scarcity and food insecurity; you create communities very vulnerable to oppression. So, my philosophy of food is [that] the most revolutionary thing we can do is fight for food sovereignty and address food insecurity [through] solidarity.”

Tiro (left) and Thabo (right) Mthembu pictured at the former Hampton Hub, a vegan restaurant and gathering space for community.

Drawing directly on BPP survival programs such as their free breakfast program, the Hampton Hub used their restaurant space, its resources, and community donations to cook nourishing meals. These included hearty batches of soup and colourful salads and sweets for a variety of programs. For the duration of a tent encampment at Regina City Hall in 2023, the brothers made and served breakfast each morning for 40 days. Most weeks throughout the summer and fall of 2024, they prepared meals for Sunday Funday, a weekly communal meal in a Heritage neighbourhood park, replete with music and a free market. During the winter, which can regularly reach temperatures as low as -30 C in Regina, the Hub prepared meals for a community-run warming centre.

In September 2024, alongside Thomson Community School, the Hampton Hub launched the Thomson Food Collective to implement a free breakfast program. The collective feeds approximately 60 children at Thomson School a rotating menu of revolutionary-inspired options, including “Rosa’s [Parks] Morning March” oatmeal and “[Fred] Hampton’s Rise and Shine Scramble.”

While some service providers in the city have a reputation for punitively limiting or monitoring access to food, the initiatives the Hub is involved in push against carceral logics of food. They reject capitalist notions of scarcity in favour of an ethics of abundance. For the Mthembu brothers, providing food is more than addressing an immediate need and the manufactured crisis of food insecurity; it is about creating networks of care. Rather than just dropping food off, the Hub and its collaborators try to cultivate gathering spaces, like Sunday Funday. Tiro says their priorities are “building community and building support” in order to have more “elasticity to our movements as opposed to being so rigid and siloed off and segregated. This [gives them] that flexibility to be more in tune with community needs by building these relationships of trust.”

Cultivating coalitions

Tiro’s commitment to coalition building echoes his hero’s. During Hampton’s brief visit to Regina, his political praxis and aspirations for building a rainbow coalition were clear: Hampton refused to give interviews to the conservative press because of how they reported on Indigenous people. Instead, he reportedly met with the executive director of the Métis Society of Saskatchewan, Harry Daniels. According to Hampton, it was critical for him to “set up some communications, set up some ties, some lasting relationships with progressive people,” especially Indigenous people, in the context of the repression of Indigenous and other progressive voices in Canada.

Demonstrating an attentiveness to the nuances of the local context, Tiro notes, “If we were to be in Oakland, most of [the] community we would be serving would be Black, but where we are situated on Treaty 4, the most oppressed community is the Indigenous [community] and therefore, us Black members of the community [...] have a moral responsibility” to show up for Indigenous causes. This is not to say that the brothers and other Black people on the Prairies do not experience systemic anti-Black violence and racism. Thabo recounts the racism he’s faced in Regina but says, “Indigenous people in this country, province, and city, have been shit on by the system continually and it has never relented [...] [It] gives you a clear lens of empathy.” Rather than advancing a Black nationalist agenda at the expense of Indigenous sovereignty, the brothers’ solidarity comes from an understanding of and an imperative to organize alongside Indigenous communities.

Today, the struggle for food sovereignty continues, as the government underfunds the Saskatchewan Income Support (SIS) program and fails to adequately address the intersecting housing and opioid crises, effectively starving community members. As this disproportionately impacts – and targets – Indigenous people, for Tiro, it is critical that the Black community and Black resistance centres “Indigenous rights […] as a pan Africanist goal.”

Rooting their work in an interconnected history of resistance to European empire and critique of settler colonialism and racial capitalism, the Hampton Hub fits into a long legacy of Black Prairie resistance.

Black Prairie resistance and refusal

Black presence in so-called Canada is simultaneously erased and used to produce national multicultural narratives, in what Black studies scholars Katherine McKittrick, Rinaldo Walcott, and Dionne Brand describe as an “absented presence.” This is heightened on the Prairies, which are often seen as white rural spaces. This imagined whiteness is central to the colonial project of dispossession, but it also conceals the long history of Black presence in the prairie region, which Black Canadian literature scholar Karina Vernon’s archival work has traced back as early as 1779 during the fur trade.

The first Black settlement in Saskatchewan, the Shiloh community, was established near Maidstone in 1910 by migrants escaping racial terror in the American South. Carol LaFayette-Boyd, the executive director of the Saskatchewan African Canadian Heritage Museum and a descendant of this period of early migration, views her ancestor’s flight from Iowa as a form of refusal and resistance. They continued to refuse conditions of white supremacy when met with racism and segregation north of the border.

LaFayette-Boyd notes that since Saskatchewan’s early Black population was “dispersed across [the province]” there were no large organized movements. Instead, Black people in Saskatchewan continually resisted systemic anti-Blackness through everyday acts of refusal. Vernon’s archival research has not only established an archive of Black Prairie writing but has also read against the grain of Black Prairie oral histories to uncover “hidden forms of protest,” often unintelligible to non-Black readers. Examples include early Black homesteader Ellis Hooks’ strategic uses of silence in archived interviews, or his community’s more audible opposition to a 1950 racist play in Breton, Alberta, during which they egged the offending parties.

Other more visible forms of protest in the archive of Black Prairie resistance include Lulu Anderson and Charles Daniels’ court cases against segregationist theatres in early 20th century Alberta as well as the first Black labour union in North America, the Order of Sleeping Car Porters, which started in Winnipeg. Black Lives Matter protests in recent years across the Prairies attest to a long-standing Black presence in the region and a consistent refusal to accept state-sanctioned violence or myths of Canadian exceptionalism.

To contend with rising fascism and Christian nationalism, both locally and globally, requires not only an analysis of the machinations of anti-Blackness, but a grounding within a long tradition of Black anti-fascist organizing.

If the erasure of blackness often includes an erasure of Black resistance, it is critical to archive a variety of refusals, from which we can draw as we organize within and without the state.

Fighting fascism

Despite Saskatchewan’s progressive socialist roots as the originator of medicare, more recently the province has elected conservative leadership for five consecutive terms. Under the Saskatchewan Party, and Premier Scott Moe’s increasingly right-wing political plays, education and health-care systems have been systematically underfunded, cuts to SIS have exacerbated rates of homelessness, and the agency of trans children has been attacked through “parental rights” Bill 137, all of which are undergirded by fascist logic. Upholding a Black anti-fascist tradition, the Hub operated as an important place to organize around these issues and provide leadership from Black community members.

While the Saskatchewan Party’s policies may not seem to directly target Black communities, Black bodies are often co-opted to signify problematic, undesirable “others.” The xenophobia that often accompanies fascism also presents a concern for the Black population in Saskatchewan which has tripled over the last two decades, largely due to immigration from African countries. It’s hard not to wonder if growing anti-immigration sentiment – reflected in recent changes in federal policy to reduce the number of foreign workers and students – had a role in the recent murder of Ghanaian international student, Alfred Okyere, in Saskatoon at the start of this year.

Although the origins of fascism are usually located within interwar Europe, American scholar-activists Bill V. Mullen and Jeanelle K. Hope have recently reframed this history from the perspective of the Black radical tradition – drawing on anti-colonial theorists such as Walter Rodney, W.E.B. Du Bois and Aimé Césaire – to call for an examination of European colonialism in Africa and Jim Crow America as early progenitors of fascism. These reframings assert anti-Blackness as one of the key components of fascism and highlight a long tradition of Black anti-fascist movements. To contend with rising fascism and Christian nationalism, both locally and globally, requires not only an analysis of the machinations of anti-Blackness, but a grounding within a long tradition of Black anti-fascist organizing.

The Hampton Hub’s Teach-in Tuesday on teacher activism for public education.

Working in tandem with grassroots and mutual aid organizations, Hampton Hub became an important place to organize for Regina’s 2024 municipal election, creating opportunities to platform progressive candidates, many of whom were racialized women, through various events, as well as to coordinate and feed volunteers. For Tiro, it is important to organize through both local governance channels and at the grassroots level. “I do think we need representation, but I'm way more interested in Marxist, socialist, grassroots organizers of all shades, creating a rainbow coalition in Regina,” he says. “We're organizing [to] support candidates that stand for the people and then they're elected and [will] be held accountable by the people.”

The key to organizing that coalition, the brothers believe, is through developing a political education. Like the Black Panther Party’s community education initiatives, the Hampton Hub regularly hosted teach-ins. On Tuesday evenings, the restaurant became a dynamic space for discussing local and international issues, as local experts and community members gathered to educate, share knowledge, and brainstorm, building a shared analysis and understanding of issues facing community members. The Hub held teach-ins on a range of topics, including public education and teacher activism, settler-colonial land theft, warming shelters, and health care. It also hosted fundraisers and community events for Palestine and in support of youth impacted by transphobic Bill 137. In addition to raising awareness, the teach-ins have led to other collaborations and direct action. For example, at the teacher activism teach-in, Keilyn Howie, a Black teacher at Thomson School, met Tiro, which led to the formation of the free breakfast program.

Thabo reflects on being inspired by the voluntary nature of the teach-ins. “People choose to come here and they [want] to listen and to be part of this conversation. And that energy [...] really awakens something in you where – especially when we’re talking about people needing help so often and you’re seeing that there is energy behind it – it really uplifts you a lot but then also lights that fire like ‘let’s fucking do this, then.’”

Becoming boundless

Through the Hampton Hub, the Mthembu brothers mobilized Fred Hampton’s political praxis and Black radical tradition, applying models of resistance to the Regina context and contributing to the living history of Black Prairie resistance.

At the end of 2024, the restaurant closed its doors, citing “the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation, and endless construction” that often made the restaurant’s block inaccessible. While the closure might be positioned within industry trends, it offers an important moment to reflect on what the Hub meant to the community, to recognize the labour and love that animated the space, and honour its entrance into the archive of Black Prairie resistance.

While there were many difficult challenges, for Thabo, “[the Hub] was family; it was community; it was love.”

“What I hope to be true is that we continue to do this work because we are grounded in the legacy of resistance not only in our family but in the whole Black and Indigenous experience,” Tiro says.

Although the restaurant space has closed, the brothers have built a network of community care that transcends the walls of the restaurant. Continuing many of their food-based mutual aid projects since the closure, the Hub has become like many boundless Black diasporic spaces: deterritorialized, mobile, and imaginatively expansive.