With the dust of the fall 2007 elections settling, many Guatemalans are breathing a sigh of relief. Another violent campaign period has come and gone and, although more than 50 candidates and activists were assassinated in the process, the lesser of evils has come out on top. Alvaro Colom and the National Alliance for Hope (the Unidad Nacional de la Esperanza, or UNE) won the presidency in a November run-off vote that pitted Colom’s social platform against the militaristic approach of former general Otto Pérez Molina. In the still-violent aftermath of the recent civil war, the elections represented a choice between rebuilding government institutions and responding forcefully to spiralling violent crime.

At a deeper level, the 2007 elections also exposed a number of power struggles currently being played out in Guatemala, clarifying the positions and tactics of the oligarchy, organized crime, the political left, social movements, and even foreign corporations. What emerged from these struggles-contrary to the warm reception so widely given to Colom’s seemingly moderate administration-was the entrenchment of the traditional elite, the defeat of the electoral left, and the opening of new opportunities in the partnership between organized crime and the Guatemalan state.

Another campaign, another step backwards

In 1996, the signing of a “firm and lasting peace” between guerrillas and the Guatemalan government ended nearly four decades of internal armed conflict. Since 1960, Guatemalans suffered state terror at the hands of a succession of military leaders and their puppets. Extreme violence reached unimaginable heights in the 1970s and 1980s as torture, rape, executions, and massacres left over 200,000 civilians dead in a savage bid to quell “subversion” while consolidating state power and organized criminal domination for a select cadre of military elite.

Since the end of the war, however, right-wing presidents representing a variety of elite factions have steadily dragged hopes for peace and meaningful reform into an abyss. Alvaro Arzú, president from 1996-99, appointed the most business-friendly administration in Guatemalan history and proceeded to halt all socio-economic reforms outlined in the peace agreements; Alfonso Portillo (2000-2003) did the bidding of General Efraín Ríos Montt, former dictator and orchestrator of the worst massacres during the early 1980s, allowing the re-emergence of paramilitary groups and the flourishing of organized crime; and Oscar Berger (2004-2007) used the repressive power of the state to crush social movements, prop up the landed elite, and intensify neoliberal state policies.

As governing administrations have contributed to Guatemala’s spiralling poverty and violence, the electoral processes that brought them to power have also deteriorated. Each campaign period since the war’s end has seen an increase in the number of candidates and their supporters assassinated, as well as a steady dose of election-related conflicts and allegations of fraud.

The 2003 elections campaign revolved around the presidential bid of General Ríos Montt, Guatemala’s most notorious dictator and godfather of the military-criminal nexus. With Montt’s bid, levels of campaign violence hit a new high: the murders of more than 30 candidates and party activists were carried out with horrific violence, including torture, mutilation and even combustion. There was a noticeable change in the climate of elections violence four years later, however: assassinations were cleaner, but more numerous. The spectacle of the 2003 attacks gave way to targeted and successful hits and, while the overall number of attacks dropped during the recent campaign period, the number of murders rose sharply to at least 54. A normalization of election assassinations seems to have sunken in, with the culture of political violence shedding showiness in favour of an equally terrifying efficiency.

Alongside the increased number of political murders, fraud and conflict festered at the local level during the 2007 campaign and vote. Every four years, Guatemalans cast ballots for all levels of government at once: they choose not just the president and vice-president, but congressional representatives at two levels as well as municipal mayors. This gets particularly sticky since the political parties that candidates run under remain the same across all levels, allowing the interests, big money, and corruption of national party coordination to mix with local conflicts and thug politics at the community level.

A new ingredient was added to this volatile mix during the recent elections, as a process of decentralization nearly doubled the number of voting tables across the country by bringing electoral stations into many communities that had previously commuted to local urban centres. While this was undoubtedly a positive step for the Guatemalan voting system, it also allowed for a mushrooming of the fraud and coercion that often takes place before and during the vote. The result was an intensification of intimidation, vote buying and violent protests, with dozens of municipalities reporting conflicts lasting beyond the voting day.

Birds of a feather: Guatemalan administrations since the peace accords

1996-1999: National Advancement Party (PAN), President Alvaro Arzú; coalition of modernizing sectors of the oligarchy.

2000-2003: Guatemalan Republican Front (FRG), President Alfonso Portillo; 1980s military elite turned organized crime.

2004-2007: Grand National Alliance (GANA), President Oscar Berger; pan-oligarchic party formed in opposition to the military-based FRG.

2008-2011: National Alliance for Hope (UNE), President Alvaro Colom; broad coalition heralded as centre-left but acting as a congregation of right-wing interests.

The contenders

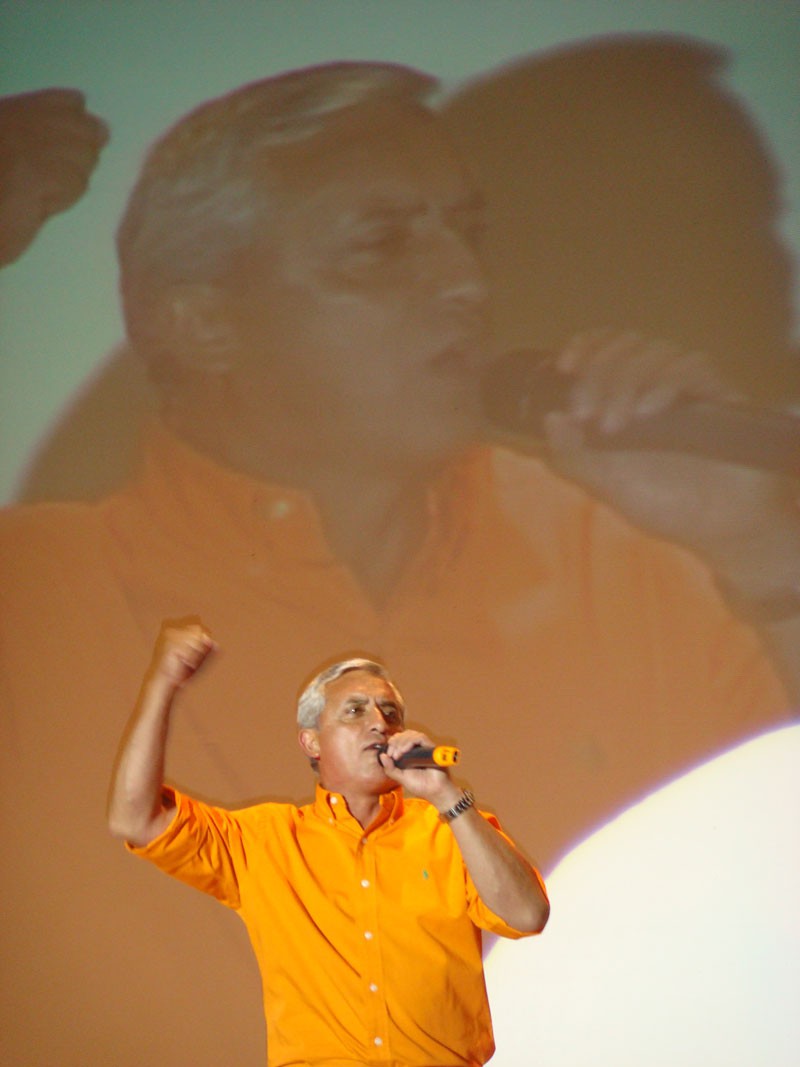

With the commotion of the first round of elections out of the way, Alvaro Colom and Otto Pérez Molina emerged after September 9 as the two presidential contenders for a November run-off. The core message of both candidates focused on Guatemala’s worsening security situation, where one of the highest homicide rates in the hemisphere is nestled within a context of street gangs, organized crime, vigilante groups and death squads, each with complex interrelations among criminal groups and between themselves and the state.

Colom’s proposal, selected by a narrow margin of victory of less than three per cent, is to fight crime and criminal organizations by overhauling Guatemala’s inept justice and security institutions; Pérez Molina had promised to use military and police forces to combat perceived criminals head-on. Two visions for Guatemala were clearly on offer in this regard, and the nearly even split of voters reflects both the primary concern with crime and violence in the country and the divide in public opinion on how best to reverse the trends.

The defeat of Pérez Molina should be understood as a victory against throwing fuel on the fire of Guatemala’s spiral of violence. Before entering party politics in 2000, the general carried out a lengthy and notorious military career, heading up two of the most feared military death squads during their final days and allegedly playing a coordinating role in the murder of human rights activist Bishop Juan Gerardi in 1998. His recent political involvement has also been tainted by allegations of connections to organized crime. For example, Colonel José Luis Fernandez Ligorría, a close advisor of Pérez Molina, is implicated in the Moreno Network criminal organization, which is widely held as controlling Guatemalan contraband.

Alvaro Colom, the new president of Guatemala, has no known connections to Guatemala’s rampant illicit sectors, but in his case it is those who have united around him who require scrutiny. Colom himself comes from a family of political activists, and his positions on social and economic policies have accurately been described as centre-left. However, the unity coalition he formed in the late 1990s has gradually become a melting pot of right-wing interests, with multiple factions of the oligarchy present alongside the military elite. In the last few years, as Colom has begun to lose control of his party and become unable to direct key votes against free trade and for anti-impunity measures, concern grows among many Guatemalans that his UNE administration will simply act as a senate of the right wing.

In contrast to the previous post-war governments, each representing one elite faction and generating intra-elite spats on the outskirts of administrative power, it is possible that the cacophony of interests active in Colom’s party will allow for new opportunities for all those involved. Among these interests, however, may be groups controlling the drug trade moving through Guatemala on its way north to the United States, as rumours about connections between UNE officials and narcotics rings have been circling for years.

Although there are major differences between Alvaro Colom and Otto Pérez Molina, as well as between their policies and the composition of their parties, at many levels their election platforms reflected a single right-wing agenda. This was achieved largely due to the fact that both candidates received their most substantial campaign contributions from the same economic powerhouse, the manufacturing empire controlled by Dionisio Gutiérrez and Juan Luis Bosch. Combined, Gutiérrez-Bosch are by far the strongest economic force in Guatemala today, and their funding of both frontrunners guaranteed them the ear of the future president.

The Gutiérrez-Bosch mastery of the campaign period also solidified one particular direction in the theatre of power struggles that is the Guatemalan oligarchy. The economic elite, having forged alliances in 2003 to defeat Ríos Montt and the return of the military and organized crime, spawned a plethora of micro-parties for the 2007 elections, each representing sectors or positions within the wider oligarchic structure. Gutiérrez-Bosch, however, preferred to fund the top four contenders, generating a presidential race with little diversity on socio-economic issues and guaranteeing their power within the next administration.

Colom’s victory also means the continuation of favourable conditions for transnational corporations, as Gutiérrez-Bosch have been major supporters-and beneficiaries-of neoliberal policies, including the controversial CAFTA free trade agreement between the United States, Central America, and the Dominican Republic. While the Guatemalan elite may continue to fight for their piece of Guatemala’s juicy pie, Colom’s administration, spurred on by Gutiérrez-Bosch, will see the country into a new era of regional and transnational capital accumulation at the expense of the majority of Guatemalans.

Notwithstanding Colom’s best intentions, then, the many interests of his party and his compromised ascent to power make probable the continuation of the trends that defined the last four years in Guatemala: the concentration of wealth and resources, the increased presence of transnational companies, the acceleration of internal and external migration for economic reasons, and the ballooning of figures for poverty across the country despite a steadily growing gross national product.

Guatemala’s Bosch League

Politics and business in Guatemala are dominated by an economic élite that is miniscule in size but severely divided, leading to constant changes in leadership behind the scenes. Recent fighting“”first between the oligarchy and the military elite, and subsequently within the oligarchy itself“”allowed the financial partnership of Dionisio Gutiérrez and Juan Luis Bosch to rise quickly to the top. Their chicken and cement monopolies have secured them the control of housing and infrastructure as well as the staple meat of millions of Guatemalans. Gutiérrez and Bosch have also benefitted significantly from neoliberal policies in Central America, dominating the changing corporate sector under the CAFTA free trade agreement. Their foray into back-seat politics seems to be just beginning: not only did Gutiérrez-Bosch fund the four Guatemalan presidential frontrunners, but the two also reportedly dabbled in foreign lobbying during a recent Costa Rican referendum on that country’s participation in CAFTA.

Left out

In stark contrast to many Latin American countries today, Guatemala is not experiencing a resurgence of the political left. In fact, the opposite was demonstrated in the 2007 elections: the majority of parties on the excessively divided left were either co-opted, voted into congressional irrelevance, or dissolved. Of the four political parties presenting leftist platforms of varying degrees, two were forced to disband because of low support in the first round of elections.

The Alianza Nueva Nación (ANN), among those demobilized after failing to elect a single congressional representative, had presented a mixture of Guatemalan and Venezuelan revolutionary language, with former guerrilla commander Pablo Monsanto proposing a “constitutional revolution.” Likewise, the formerly rightist Democracia Cristiana Guatemalteca (DCG) party no longer functions after attempting a comeback through the intellectualist anti-neoliberal discourse of Marco Vinicio Cerezo.

The progressive party that made the strongest advance in congress, the recently-formed Encuentro por Guatemala (EG), ran the indigenous activist and 1992 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Rigoberta Menchú as presidential candidate and elected four progressive congressional representatives.

However, like the parties of Colom and Molina, the EG accepted funding from Gutiérrez-Bosch, and the EG vice-presidential candidate, Fernando Montenegro, hails from the traditional landholding elite. He served as head of the coffee farmers’ association during the coffee crisis of the early 2000s that left thousands of rural Guatemalans without work, and more recently as president of the formidable multisectoral economic cooperation board, CACIF. It is no surprise, then, that EG’s platform, while excellent in terms of the protection of indigenous and human rights, severely lacked any socially oriented economic policies.

Only the URNG-the leftist guerrillas that had re-formed as a political party following the peace accords-continue to function as a genuinely leftist party; however, with its two congressional representatives and relatively minimal mayorships, the party has little room for maneuvering. The URNG’s well-defined opposition to current economic policies and articulate proposed alternatives have made the transition to the neoliberal era, but will continue to fall on deaf ears in the Guatemalan congress.

It was with municipal posts, contested during the first round of voting, that progressive parties had hoped to assert their relevance and local influence, but even there the left failed to make an impact. Of 332 mayors elected across the country, a total of just eleven candidates were chosen from left-wing parties: two from the ANN, one from the DCG (all three of which will now have to change political affiliation with the demise of their parties), one from Menchú‘s EG, and seven from the URNG.

Still, the Guatemalan left can claim one major victory from the 2007 elections, one that bridges social movements and party politics. In the municipality of Sipakapa, San Marcos, where community organizations have been fighting against an open-pit gold mining project carried out by Canada’s Goldcorp Inc., an anti-mining coalition managed to gain the mayorship. Their electoral victory represents the institutionalization of opposition to a destructive development model-a small but significant shift in favour of the type of community-based alternatives proposed by social movements.

In fact, for Guatemala’s poor, the country’s social movements present virtually the only ray of hope in these dark days. From community referendums on exploitative economic projects, to the articulated alternatives for land conflicts proposed by campesino groups, to national human rights monitoring, Guatemalan community organizations respond tirelessly to a continual onslaught of attacks and violations. And while the elections may have dashed many hopes for the formal representation of progressive organizations, Guatemala’s social movements wisely saw the highly corruptible electoral process as just one aspect of the wider struggles that promise to continue throughout the Colom administration.

Unsettled scores

Many of Guatemala’s power struggles surfaced during the 2007 elections and were fought on its platforms, but the issues lying beneath the campaigns remain far from resolved. While Guatemalans narrowly rejected General Pérez Molina’s proposal for a military-style response to violent crime, the internal divisions and multiple interests within Alvaro Colom’s incoming administration will make significant reform next to impossible. And with any well-intentioned hands tied, the political climate will continue to be defined by the squabbling of elite factions rather than in the pursuit of policies that would seek to promote peace or further social justice.

One issue that may become more apparent under Colom’s presidency is the political power of narcotics-based organized crime. From the municipal level through the major parties, the reportedly heightened financing of 2007 elections campaigns by criminal groups-coupled with the lack of an identifiable elite position within the new administration-may open new doors in the manipulation of the many state institutions already infiltrated by narcotics rings.

With the military defeated as an organized political force with the 2003 elections, the elite interests most likely to shape the political agenda over the next four years are the three remaining pillars of power in Guatemala: the various factions of the traditional economic elite, entrenched in institutional power but internally divided; the ostensibly neutral but enormously influential transnational corporations; and the organized criminal groups that are perfectly happy to operate within any political climate that is willing to ignore their activities. This is a situation of roiling power struggles, but essentially also one of cohesion and co-existence: the status quo will continue to be shaped by a cast of characters that will each enrich themselves off of a corrupt and violent system maintained in conjunction with their competitors.

Simon Granovsky-Larsen has worked with social movements in Guatemala since 2003, and provided human rights accompaniment to members of the left-wing Alianza Nueva Nación during the recent elections.