I didn’t go to La Libertad, Petén, for the fried chicken. I went because of the war.

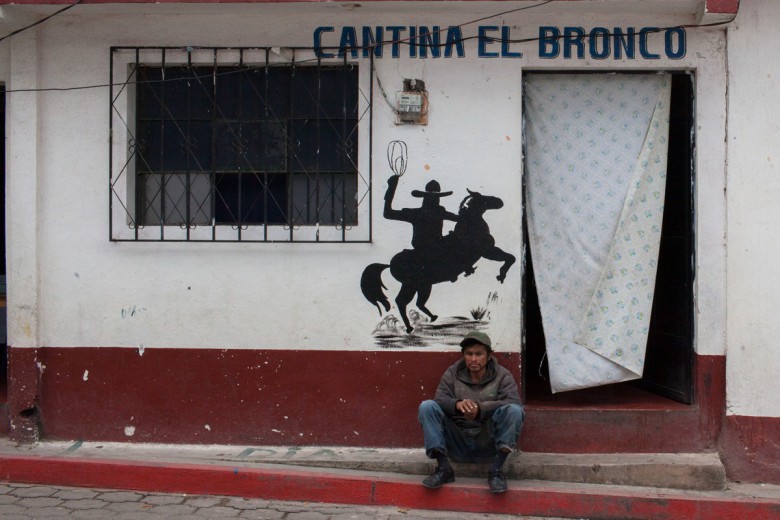

That said, for three nights in a row I sat on the same plastic bar stool looking out over the main road through town and ate the best chicken I’d ever tasted. The cook, bills folded into her apron, kept watch over a huge, cast iron pan filled with dozens of legs and breasts frying under a generous portion of oil. Each night I was in La Libertad, I would venture out for fried chicken after dark, when the temperature settled down to a comparatively comfortable 30 degrees. From my spot at an outdoor table, I would sit, eat, and watch.

Everything seemed to happen at once: bikes and mototaxis stopped, started, and turned; women grabbed their children and dodged across the street; buses came and went; trucks blazed through at full speed. Even after dark, amid the traffic, people were selling mangos (ripe or unripe), dictionaries, drinks, and clothes. A group of pharmacy workers in white uniforms were getting off shift. One night, armed park rangers sat a couple of tables away and ate, but police and soldiers, a fixture on the main drag during the day, seemed to disappear after dark.

It feels so normal, I kept thinking to myself. It doesn’t feel like war. And if La Libertad is known for anything these days, it’s war. I expected some kind of tension, perhaps an unofficial curfew, intensive checkpoints, or convoys of SUVs with tinted windows.

Something.

Guatemala is back in the news, and the news isn’t good.

The Central American country is garnering more media attention as an emerging hot spot for organized crime groups. But while media coverage has focused on atrocities and the incursion of organized crime, a new oil rush is taking place in Petén, the same increasingly militarized northern area coveted by criminal groups.

In May 2011, the municipality of La Libertad was the site of the deadliest massacre in Guatemala since the 36-year internal conflict officially ended in 1996. Twenty-seven day labourers were killed on a ranch called Los Cocos. Most of the dead were Indigenous Q’eq’chi men. When authorities entered the ranch the day after the massacre, they found 26 bodies and 23 severed heads. “What’s up, Otto Salguero, you bastard? We are going to find you and behead you, too. Sincerely, Z200,” read a message in Spanish written in human blood on the side of a building beside the bodies, supposedly from a local cell of the Zetas.

Images of the carnage at La Libertad were posted online showing heads scattered in the grass and soldiers guarding decapitated bodies that had their hands bound, shocking the world and evoking memories of the darkest years of Guatemala’s history when these kinds of events were almost commonplace in some rural areas. But unlike the old days, it wasn’t men in government-issued uniforms doing the killing. This time, it was blamed on the Zetas, a narcoparamilitary group originally formed by Mexican special forces that deserted and joined the Gulf Cartel, from which they split in 2010.

“More than controlling the distribution chains and infrastructure needed to run the day-to-day operations, the Zetas are focused on controlling territory,” reads a September 2011 report prepared for InSight Crime, a George Soros-funded think-tank. The report, based mostly on information from government sources and newspaper articles, points to the massacre in La Libertad as the first incursion of the Zetas into Petén. As far as can be proven, drug traffickers who identify as Zetas are active in Petén. Fox News even reported on a banner, hung in late March in the state’s capital, threatening death to civilians in Petén and signed by Z200. Following the massacre, the government declared a state of emergency that lasted until January of this year.

To claim that Petén is Zetas territory, however, is to ignore other important interests in the resource-rich region, which is bigger than Belgium.

For one, there are established drug trafficking families in Petén who haven’t ceded control of the lucrative transshipment market to the Zetas. But the armed groups with the most visible presence in the region are the Guatemalan police and army. They were an ever-present part of the daytime street life in the half-dozen cities and villages I visited there, driving around in the backs of pickup trucks or walking around in groups.

One morning, together with a photographer and a couple of locals, I visited the Lacandón National Park, which is also in the municipality of La Libertad. Hundreds of peasant families from the community of Nueva Esperanza were removed from the park last summer on the pretext that they were involved with narcotrafficking. We entered the park with a couple of community members, and it didn’t take long before police armed with semi-automatic weapons arrived, recorded our names, and nodded approvingly when we made motion to leave. Later, we were warned against entering the Laguna del Tigre Park because our presence at the various army checkpoints on the way into the park could create problems for the people we wished to visit.

Both of these protected areas are heavily militarized, and both are reported to be places where drugs are moved into Mexico. But they’re also home to dozens of peasant communities and are among the areas of Guatemala with the most abundant natural resources. The events unfolding in Petén are much less familiar, but merit closer attention – especially from Canadians.

To get into the Laguna del Tigre National Park, you have to travel through El Naranjo, a busy frontier town bordering a river that flows to Mexico. While we visited, soldiers kept watch over the riverfront; rickety, wooden motorboats came and went; other armed men without uniforms stayed back under the shade of nearby shopfronts; and a small sign at the loading area displayed the logo of another powerful group operating in the area: Perenco.

Perenco is a Paris-based oil company that produced and exported over 3.6 million barrels of crude oil last year when oil displaced cardamom as Guatemala’s fourth export, after coffee, sugar, and bananas. The firm operates 47 wells known as the Xan Field inside the Laguna del Tigre National Park, forming a footprint anyone with access to Google Maps can observe. The oil travels down a 475-kilometre pipeline, also owned by Perenco, which leads to the company’s refinery near the town centre of La Libertad and then continues on to the company’s terminal near Puerto Barrios on the Atlantic coast. Perenco acquired the operation from Canada’s Basic Resources in 2001.

According to one local resident, who asked that his identity be concealed for fear of reprisals, the militarization of the area has more to do with protecting oil interests than it does with fighting organized crime.

“In the case of Perenco, it’s a company that’s providing financing for the army of Guatemala to install itself in the area,” he said, pointing out that six small military bases and at least 250 soldiers, part of a green battalion, exist inside Laguna del Tigre. Some of these soldiers have taken part in forced evictions of communities living inside the park and are currently responsible for what amounts to a state of siege for those still living inside. Not only are the 25 to 30 communities inside the park forbidden from cutting a tree without a permit, they are under constant pressure from soldiers and armed park rangers.

“First, the mere presence of soldiers is something that makes the communities feel uncomfortable because of the memory of the people, when they see a soldier, they see someone who is there to kill,” said the resident, who travels regularly into the area. “Second, they built a military outpost on the road, 15 or 17 kilometres from here, from El Naranjo, where they are controlling everything that the communities bring into the park.” He said soldiers prevent community members from bringing in provisions, work tools, and materials they need for their homes, like corrugated zinc, cement bricks, sand, and rebar. “They’re pressuring them by denying them access to things they need, which is another way of pressuring them so that they’ll leave the area on their own,” he said.

Perenco has deflected attention from their impacts on the park by stating on their website they “recognise the serious nature of the problems facing the Park, such as those caused by migrant communities [sic] illegal slash and burn farming techniques.” The government of Guatemala also blames people living inside the park for environmental damage to Central America’s largest wetlands. “I will not tire of saying that the biggest threats to the Laguna del Tigre Park are cows and not the pipes of Perenco company,” said former president Alvaro Colom in 2010.

Ex-Petén governor Rudel Mauricio Álvarez claims that during his administration, which ended earlier this year, the choice was between oil or drugs. I met Álvarez in an open, modern café in Flores, the picturesque capital of Petén, following a Twitter exchange spurred by the word narcoganadería, or narcoranching, meaning large scale ranches used as cover for drug trafficking activity.

“That’s the question. What’s worse, what’s more damaging: oil that only impacts the 450 hectares where the fields are, or narcoranchers who have 140,000 hectares?” he asked. “Everyone, the environmentalists and everyone else went against oil … They make the real problem of the protected areas invisible,” he said, pausing briefly before coming back to his own question. “The problem isn’t oil extraction. The problem is narcoranchers.”

No one I spoke to denied that Laguna del Tigre was part of a trafficking route where Colombian cocaine arrives on private airstrips and is then moved out to Mexico. Opinions differ on how involved the dozens of communities inside the park are with trafficking. Álvarez claimed most of the communities are invaders, funded by narcodollars. But unlike in parts of Mexico where the drug trade dominates, I didn’t see a single showy SUV while I was in Petén. My source in El Naranjo said the narcos keep to themselves, flying in and out of the area, while the communities – many of which were settled by families displaced during the internal conflict – survive off of their basic crops of corn, beans, and squash.

One thing is clear. The presence of drug traffickers in Laguna del Tigre hasn’t affected oil production. In fact, there’s a renewed interest from oil companies in Guatemala’s oil.

Over the past little while, a handful of Canadian oil companies have made their own moves into Guatemala. Calgary-based Quattro Exploration and Production, which is actively extracting oil in Saskatchewan, has acquired almost 350,000 hectares worth of oil concessions in Guatemala since November of last year. Their most recent acquisition is a concession block adjacent to Laguna del Tigre, itself within the Maya Biosphere Reserve. Other companies, like Pacific Rubiales and Truestar Petroleum Corporation, have also recently been active in Guatemala.

Oil is only one of the super profitable industries in Petén. An elite-driven megaproject known as Cuatro Balam proposes biofuels and large-scale agriculture in the south of Petén as well as increased spending on infrastructure for mass tourism, partially funded by groups such as the Inter-American Development Bank. Corporate-linked conservation groups, like the New York-based Wildlife Conservation Society, continue to claim vast tracts of land as park. There is also the threat of new hydroelectric projects, five of which are proposed along the Usumacinta River which activists say would flood 35,000 people off their land.

Few, if any, of the profits from these illicit or licit economic activities will ever make it to Petén’s poor majority. They remain the most likely to be displaced from the land they depend on for survival and the most likely to lose friends and loved ones as the drug war escalates in Guatemala.

Amid all of this, Guatemala’s new president, Otto Pérez Molina, a hardline former general who campaigned on a tough-on-crime policy, has made public calls for drug legalization. Some analysts believe that Pérez Molina, with his leading Patriot Party, which has an important support base among soldiers and veterans, is between a rock and a hard place. To effectively interrupt the flow of drugs, he’d have to fight against his own: the army, long known to be enmeshed in the drug trade.

Regardless of Pérez Molina’s rhetoric, Guatemala continues to arm more soldiers and police, supposedly to fight drug trafficking, following the U.S. State Department’s strategy in the region. Stephen Harper announced in April that Canada would join the U.S. and Mexico in supporting a new drug-related security strategy in Central America. Increased violence and paramilitarism, which have already reached staggering levels in Petén, are known side effects of U.S. anti-drug policy. “A 10 percent increase in U.S. military aid was associated with a 15 percent rise in paramilitary attacks in regions where there was a Colombian army base, compared to other regions,” stated economists, cited recently in Foreign Policy magazine.

Today, after more than a decade as a testing ground for U.S. drug policy – during which an estimated four million people were displaced, 50,000 disappeared, and thousands of political activists, dissidents, unionists, and environmentalists were murdered – Colombia has the fastest growing economy in Latin America.

The hard lesson from Colombia is that, unfortunately, drugs and oil do mix, and there’s no longer any doubt that the policies tested out in Colombia are being applied in Guatemala. When Hillary Clinton visited Guatemala to announce funding for U.S.-led anti-drug initiatives in Central America last year, she was explicit that her government was applying strategies previously used in Colombia and Mexico.

“We need to keep in mind that Colombian President Santos, like Pérez Molina, wants to expand Plan Colombia, which doesn’t just mean strengthening the fight against narcotrafficking but actually means converting it into a form of paramilitarism in order to generate a new kind of counterinsurgency – not against social movements but against Indigenous communities,” said Maximo Ba Tiul, a Mayan Poqomchi analyst based in Alta Verapaz. “It’s the remilitarization of Guatemala as a patriotic project.”

The Return of the Guatemalan Military

Timeline By Simon Granovsky-Larsen

At the end of Guatemala’s 36-year internal armed conflict in 1996, the military was ordered to scale down in size and mandate. With many officers holding onto influential political positions, however, the military was able to block significant reform and orchestrate a gradual return to power. There have also been important advances against impunity, including sentencing for wartime massacres and the trial of dictator General Efraín Ríos Montt, but these have been hard won alongside increasing military power.

1999: Military Reform Defeated

A referendum on measures recommended in the peace accords was defeated by less than 1%. Racist fervour against Indigenous rights recognition led the No campaign, but the military was able to hold on to legal responsibility for internal security in the process.

1999: Party Elected which was Founded by Former Dictator

The Guatemalan Republican Front (FRG) wins the presidential election under civilian candidate Alfonso Portillo. General Efraín Ríos Montt, responsible for the worst period of genocidal massacres during the war, is re-elected to Congress and remains head of the FRG.

2000: Return to Internal Policing

With their role in internal security affirmed by the defeat of peace accord reforms, the military heads back to the streets to take part in police patrols, anti-narcotics, and guarding prison perimeters.

2003: Land Evictions

Since 2003, when soldiers took over the El Maguey farm, the military has participated in evicting land occupations and communities of small farmers from contested land. Among hundreds of cases, the military participated in the eviction of over 800 families from 14 communities in the Polochic Valley in 2011.

2005: Anti-Mining Protester Killed by Troops

Soldiers shot into the crowd at a protest blocking mining equipment from reaching the Canadian-owned Marlin gold mine in San Marcos. One man was killed.

2006: State of Prevention, State of Emergency

Since 2006, the governments of Óscar Berger and Alvaro Colom have declared short-term measures to increase military control and limit constitutional rights. Many of these were ordered in the department of San Marcos, where mobilization is strong against transnational mining and electricity projects. Activists have denounced abuses under the measures.

2009: Wartime Bases Reopened

President Alvaro Colom reopened a notorious military base in the Ixcán region where more than 100 massacres were committed during the armed conflict. The region is now important for a mega-highway project, and communities have organized against its construction. Other wartime bases have since been re-opened, as have new ones.

2010: State of Siege

The first “state of siege,” or martial law, issued since the end of the war was ordered in December 2010, ostensibly to combat drug traffickers in the department of Alta Verapaz. A second of the decrees, which include the suspension of civil liberties and temporarily hand political control to the military, took place in the Petén in 2011. The third instance of martial law–in Barillas, Huehuetenango in May 2012–made clear the government’s intention to use military force to suppress social mobilization, when it was ordered to shut down protests against a Spanish hydroelectric project.

2011: Wartime General Elected President

Retired general Otto Pérez Molina, who oversaw counterinsurgent slaughter in the highlands, is elected to a four-year term as president beginning January 2012. Pérez Molina has asked to have the ban lifted on US military aid to Guatemala, in the name of the war on drugs.