I am as bored of bashing hipsters as anyone. In fact, I may be as fed up with hipster bashing as I am with the hipster phenomenon itself, in all its varieties. What is tiresome about most critiques of hipsters is not that they predictably fixate on the easy target of a repetitive fashion, but that these critiques are almost always superficial and ahistorical. Annoyance over tribal hipster codes is too often itself just tribal. Either that or it never surpasses, “If you’re going to look like a logger, better learn how to use a chainsaw” (not that I don’t have a lot of sympathy with that sentiment).

What we fail to talk about is the fact that hipster aesthetics have some pretty troubling historical antecedents, which, when juxtaposed with current realities, become even more disturbing. What I find chilling is that here in my own place and time, haunted as it is by its colonial history, I’m seeing men adopt a late 19th-century white male frontiersman style and acting as if it has no historical significance.

Why are political-historical critiques of this ubiquitous, nearly decade-old style so absent? Maybe it’s because if you even tentatively point out problems with hipster codes in a casual conversation, even non-hipsters can get very exercised about it. Try it. People seem to want to dispute that retro aesthetic references mean anything or have any significant connection to a particular history. You might get dismissive reactions like, “C’mon, meaning is fluid” or “Anything goes these days,” or “Just because I’m wearing a haircut we call the ‘Nazi Youth’ doesn’t mean it has anything to do with Hitler; Hitler is dead,” and so on. If you propose that aesthetic choices aren’t purely random, you quickly find yourself in an unpopular minority in the room.

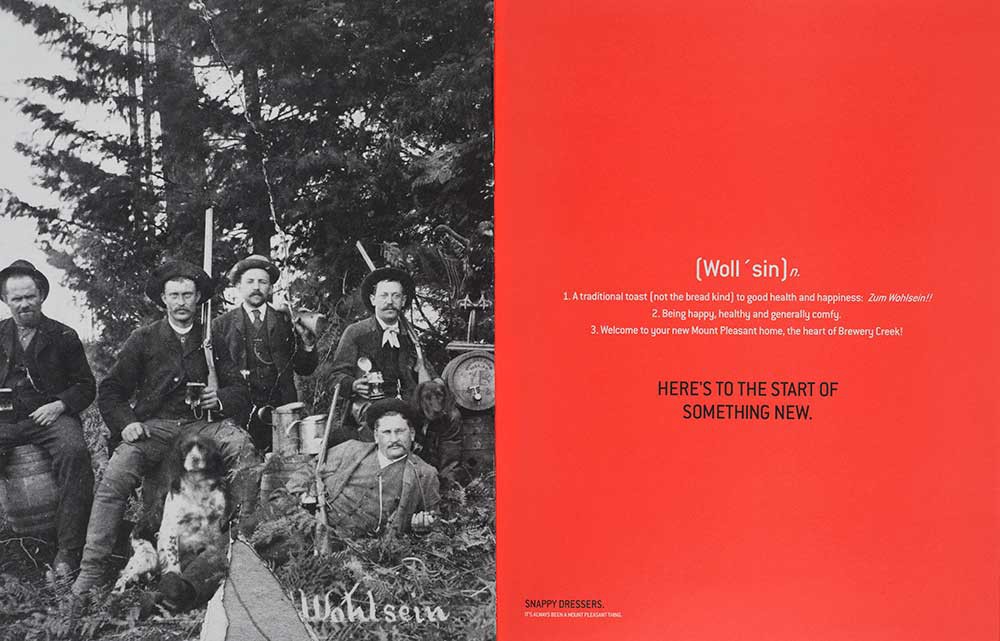

Unpopular or not, I want to talk about what the “heritage hipster” phenomenon means, particularly now that it is the face of the wave of gentrification hitting Chinatown and other historic neighbourhoods in East Vancouver. Instead of fading away after a few years the way fashions generally do, this North American pioneer style instead seems to be gathering steam. Is this a coincidence?

As anyone who has watched the satirical Pacific northwest TV sketch show Portlandia knows, the “heritage hipster” style hearkens back to late 19th-century white males in North America. Portlandia dubbed it the “Dream of the 1890s.” The style’s historical referents are actually all over the place – an amalgam of merchant or pioneer styles from 1850 to 1910, with a little Depression-era 1930s, and some 1940s and ’50s laid overtop. But the 1890s (that lesser-known decade of catastrophic economic depression) seems to be its magnetic centre.

The people in my neighbourhood

I live in a diverse and historically conflicted part of Vancouver, right at the confluence of Chinatown and an area known as the Downtown Eastside (DTES). It is the oldest part of Vancouver and one of the poorest postal codes in the country. Because it is close to downtown, condo tower developers have recently set their sights on it in what can only be called a land rush, one that our developer-controlled city hall has done nothing to decelerate. In Vancouver’s infamous climate of real estate speculation, this neighbourhood is now experiencing skyrocketing rents, renovictions, and demolitions that are quickly driving out the neighbourhood’s inhabitants: an aging Chinese population, the urban poor, many First Nations people, low-income workers, and the homeless.

Coincidentally – or maybe not – much of this neighbourhood dates precisely from the 1890s. Chinatown was founded in the mid-1880s but only really grew to a noticeable size and population in the following decade. Chinese settlers as well as immigrants of many other origins lived here, working either in the colonial resource economy, including the Hastings Mill, or in the service sector that grew up around it. In other words, this neighbourhood was not solely populated by white lumberjacks or chaps with waxed mustachios who looked as if they’d just exited a barbershop quartet.

“… that Canada should remain a white man’s country … is highly necessary on political and national grounds.”

– William Lyon Mackenzie KingIn Chinatown, the 1880s, ’90s, and early 1900s were marked by constant conflict with a city government that habitually imposed repressive racist laws, including curfews, bans on traditional barbecue (a restaurant and social mainstay), and other regulations clearly targeted at that specific cultural group. This is quite apart from the burden of the federal Chinese head tax of 1885.

Tensions ran high in the city, and anti-Chinese racism, only legitimated by all the racialized regulations, carried with it the threat of intimidation and violence. Finally, on September 7, 1907, white men belonging to a group called the Asiatic Exclusion League marched to Chinatown, beat up dozens of Chinese men, ransacked stores, and broke windows before moving on to the Japanese neighbourhood of Nihonmachi. The resulting riots in Chinatown lasted for several days.

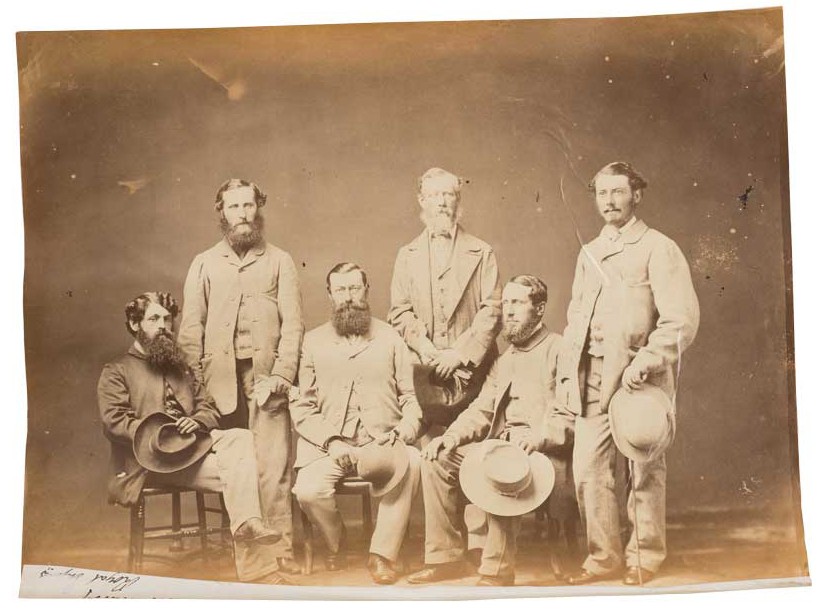

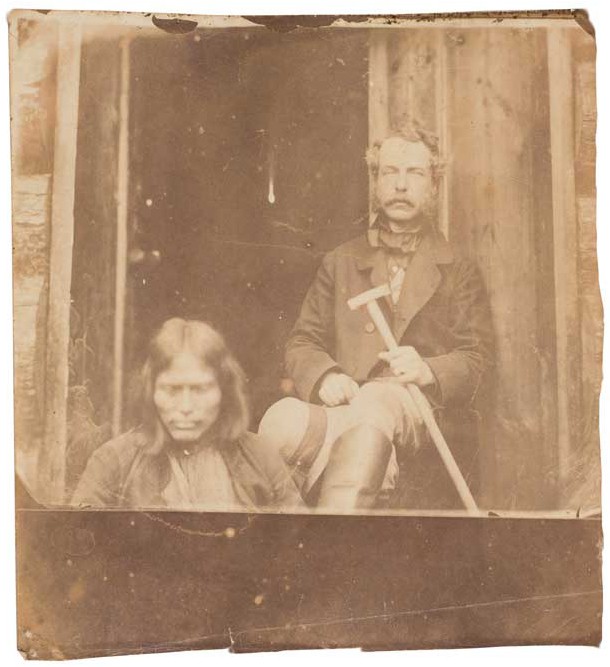

The early history of Chinatown and the DTES is only one element here. As I think most are aware, Vancouver was built on land taken a few decades earlier from Coast Salish peoples – Musqueam, Tsleil-Waututh and Squamish – without so much as a treaty. Of course, this was part of the systematic, Canada-wide process of driving First Nations from their land and way of life by forced removals, deliberate starvation, residential schools, and other tactics that are now relatively well-known. The photo that opens this article, the one showing bearded white men in B.C. in 1859, was taken smack in the middle of this era, as was the photo below.

While some of this racist local history may be known, it seems that many Canadians still aren’t aware that this was an era of overt white supremacism. It appeared at all levels of government, from local Vancouver city politics to the provincial legislature, to laws enacted by prime ministers John A. Macdonald and William Lyon Mackenzie King.

Even if the general Vancouver public knows little of the details of early colonial history, there have been so many high-profile reconciliation efforts in recent years that anyone who lives here and who doesn’t at least vaguely sense these histories would seem to be indulging in some degree of studied oblivion. In B.C. and across the country, there has been a marked resurgence of actions by First Nations, notably against resource development on traditional lands but also to address long-standing urban and housing issues. Idle No More, a movement initiated by three First Nations women and a settler ally in December 2012, was a clear sign of an Indigenous population increasingly organizing against a colonial system that, like the Indian Act of 1876, still persists. In 2014, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission finished its hearings on issues that included residential schools; the year also saw the dramatic Supreme Court win for First Nations in the Tsilhqot’in decision.

Three key non-white communities in B.C. also experienced a reconciliation or reckoning of racist history in 2014. There was the 100th anniversary of Vancouver’s shameful Komagata Maru episode (in which a ship bearing South Asian immigrants was refused landing in Vancouver harbour before being sent back to a perilous future), which included a federal apology to the Indian community; there was the City of Vancouver’s apology for the Second World War internment of Japanese Canadians; and finally, there was the B.C. apology to Chinese Canadians for the 1885 head tax. However, these well-publicized processes have been concurrent with the accelerated luxury condo development in the exact neighbourhoods often associated with these communities. And into that complex matrix blithely walks a neatly coiffed, Paul Bunyan-style frontiersman.

“You can never make good Canadian citizens of them or their descendants and it is just as necessary to keep them out as it is to keep out the Chinese. Most of them are big strapping fellows, men who have fought in British regiments in the little Indian wars, but their ideas and their ways are not ours, nor can they ever be so. These people from India come here alone just like the Chinese, and nothing on earth could make them Canadians.”

– R.G. Macpherson, Vancouver MP, to Prime Minister Laurier, September 21, 1906Now that this 1890s lumberjack style has solidly entered the mainstream, I think it is fair to start asking a few questions. Even if you could, for yourself, somehow surgically remove the colonial pioneer aesthetics of that time from their origins, how can you guarantee that others will deem your efforts a success? What fantasy 1890s are you in, exactly? What if, inadvertently or not, you are helping to whitewash Canadian history, and what if lumberjack nostalgia functions to romanticize and legitimate the colonial system and economy we still live under in Canada, and particularly in B.C., with its ever-colonial resource extraction (exporting raw logs) and its nearly perpetual urban land rush?

Settlers redux

A couple of years ago, as buildings in Chinatown and the DTES emptied out for planned condo developments, and as storefronts became available either as placeholders or as deliberate window-dressing for future condo locations, hipster joints full of antlers and other pioneer accoutrements began to appear overnight. There was no visible attempt to work with the local historic context.

Shops with ampersanded “anglo” names arrived (Jones & Smith? Smith & Wesson? Bear & Buck? I can’t remember), and so did restaurants with generic settler and frontier decor. I am not suggesting that incoming merchants should have adopted a twee chinoiserie aesthetic and everything would have been fine. But for many local residents, all this dressing and decorating like a white 1890s settler in Chinatown seemed audacious, especially in the context of a wave of condo-driven gentrification.

I had wanted to write about this style for years, but it was the recent confluence of all these elements that suddenly threw the 1890s hipster period drama into starker relief. In light of both the history of Chinatown and the DTES, this style of dress and boutique chic looked disingenuous at best and blatantly colonial at worst. The alibi usually given for this fashion is that it expresses a desire to return to a DIY, pre-consumer-capitalist style of craftsmanship, but since there are so many other aesthetics that hipsters could have chosen to fulfill this function, this explanation doesn’t wash. And the defence that the style is meant to be ironic seems weak. I don’t detect any real irony in it – quite the opposite – but if irony is the intent, who is that irony for?

As an aside, I would also add that even without the racial and colonial issues, I’d have a problem with this style for reasons involving its disingenuousness around gender and class. There isn’t space here to deal with its element of class tourism, but the gender component is more disturbing. Why has there been no discussion of this style’s near-100 per cent male adoption? A casual survey suggests that no one can identify a true female equivalent, or at least not one that is worn in the public realm. (Tellingly, burlesque and Victoria’s Secret were suggested as the probable match.) Indeed, how could women (white, let alone non-white) adopt an 1890s’ style in the same casual way? Somehow I don’t feel like wearing long dresses and not having the vote.

For that matter, the heritage hipster is only one of many traditionally masculine styles that are currently being dusted off with a great deal of enthusiasm and that seem nostalgic for some sort of old-school white masculinity. For anyone who thinks this reinstated male code isn’t a serious affair, note the high-profile case in Regina last year in which a frontier-style hipster place called Ragged Ass Barbers refused to give a signature male haircut known as a “hard part” to a prospective female customer purely on the grounds she was not male (they don’t serve women).

So. Are our historical aesthetic references innocent or not? Are fashion and culture in general not a bellwether? Let’s briefly entertain the opposing view – that style does not express often-unconscious desires, and that culture consists of items that spin meaninglessly in a blender, conveniently unmoored from history. In that scenario, how is one style ever chosen over any other? Are our choices purely random? Is it merely an accident that people have retained an 1890s aesthetic for more than nine straight years – highly unusual in fashion – in this time and place? Or is it a deeply meaningful code designed to assert a particular type of historical entitlement, in terms of white male privilege generally and land title in particular?

Increasingly, it seems that heritage hipsters are appropriating the garb of an earlier colonial era as an aesthetic cover for their entrepreneurial role in this one, all while overwriting local history with their own self-justifying myth of origin. This is one of the few instances where I agree with the otherwise annoying New Age maxim that everything happens for a reason.