Jobs. In a nutshell, this is the solution proposed by government and industry for communities facing high levels of poverty and unemployment in northern Alberta and Saskatchewan.

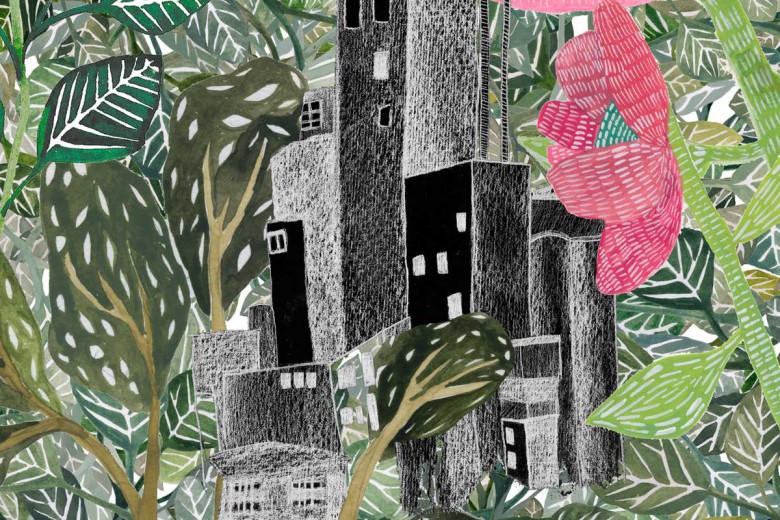

Economic development based on resource extraction and other high- impact activities continues at the expense of traditional Indigenous land-based economies. While military, oil and gas, and uranium industry development in traditional Dene, Cree, and Métis territories offers some wage labour, it displaces traditional labour such as hunting, trapping, fishing, and gathering.

“Once there’s development in an area, we’re shut off,” Brian Grandbois, a longtime land defender from Cold Lake First Nation in Alberta, told Briarpatch. “The energy corporations have access to Dene Nene [land] and the Denesuline are reduced to beggars and trespassers on their homeland.”

Sixty years ago, the construction of the Cold Lake air force base and the million-hectare Cold Lake Air Weapons Range (CLAWR), spanning the Alberta-Saskatchewan border, resulted in the displacement of many Indigenous people from their traditional territories. The CLAWR is Canada’s only tactical bombing range, and is now home to oil and gas extraction activities as well.

Aside from a land claim settlement concerning the military base, the Cold Lake First Nation band council has also signed agreements with hydrocarbon corporations, and owns a number of contracting companies serving the military and oil and gas industries.

“They’re extracting huge amounts of resources, both in gas and oil. You know, the Native people might be small players,” Grandbois told Briarpatch in an interview. “But we were promised that we’d be able to train our people and have steam engineers and people, you know, with education, to fit into that whole economic scenario. But if you look in the Air Weapons Range today in 2012, you’ll find the Denesuline are cleaning toilets for executives.”

Not only are local First Nations workers relegated to the lowest tiers of employment, but when industry, money, and economic opportunity take precedence over the survival of future generations, the price tag is high, says Grandbois.

Cold Lake First Nation members are permitted to hunt inside parts of the CLAWR on weekends, unless the Canadian Forces decide otherwise due to military exercises or other events. Oil and gas extraction both in and out of the CLAWR has further reduced the accessible land base. “Hunting was always a part of the Dene culture…But the Denesuline of Cold Lake now have nowhere to hunt,” says Grandbois.

Over the past six decades, military and extractive industry development in the area have steadily taken over the lands used for basic survival, and continue to leave toxic waste behind.

“Nobody traps anymore. A few odd people fish,” Cold Lake Elder Sam Minoose told Briarpatch in an interview at Palmbere Lake. “All the old berry patches are fenced off. We have to go miles, like into Saskatchewan,” he says. Minoose is one of many people from Cold Lake and other areas dominated by industrial development in northeastern Alberta who now travel to Beauval and elsewhere in Saskatchewan to pick berries and gather medicinal plants.

When berry-pickers cross the provincial border, they find that even further north another industry continues to expand. A Cameco billboard along the roadside promotes uranium mining, proclaiming that Cameco is “Canada’s #1 industrial employer of Aboriginal people.”

Northern Saskatchewan is the leading global producer of uranium, and home to all uranium currently mined in Canada. Two of the world’s leading uranium mining companies – Saskatoon-based Cameco and French corporation AREVA – dominate the landscape. The province’s Northern Administrative District has a population of almost 37,000, approximately 80 per cent of whom are Indigenous – principally Dene, Cree and Métis.

The effects of decades of uranium mining are felt throughout the North. At a Survival Celebration Camp in August 2012 at Lac Île-à-la-Crosse’s South Bay, Elders from Patuanak, Pinehouse, and beyond explained that their opposition to a potential nuclear waste storage site near their communities is informed in part by the changes they have seen in their traditional lands over the course of the development of Key Lake and other uranium mines. Speaker after speaker spoke of the gradual disappearance of wild game and other animals. “There’s definitely something wrong in our trad-itional areas,” Dene Elder Delia Black told participants at the camp through a translator. “All the wild food that we used to have, it’s not there anymore,” she said.

Traditional herbalist Victor Mispounas knows the lands, forests and lakes of northwestern Saskatchewan well. He whistles as he walks, skirting around the Lac Île-à-la-Crosse lakeshore, looking for wild mint. His tall, wiry frame disappears into the brush only to reappear seconds later, pointing out another medicinal plant and explaining its use. “There’s not too many traditional people like me who practice herbal cures. It has almost all been lost – everything, just about everything lost,” says Mispounas.

People travel from near and far for healing at Victor Mispounas’ home on the La Plonge reserve, part of the English River First Nation. He learned most of his plant knowledge in secret, at a time when traditional practices were forbidden by federal government agents. The intergenerational teaching of medicinal plant knowledge was interrupted by the residential school system, and the fear of being jailed or having one’s children taken away for using traditional methods of healing.

Seated at a picnic table by the shore of South Bay as storm clouds roll in, Mispounas tells Briarpatch how he was one of the lucky ones and how he gained the knowledge that allows him to carry on his work today. “There were just a few odd ones like my parents, [who] taught me in secret,” he says. He recalls how his parents of mixed Cree, Dene, and Saulteaux descent instilled in him from a young age the need to stay silent about what he learned with them in the bush. “Even at that time, I remember them saying, you know…‘whatever we teach you here, don’t tell anybody. Don’t let nobody know, even your best friend.’” Today, Mispounas is an active member of the Committee for Future Generations. In the summer of 2011, he participated in the 7,000 Generations Wanska! walk from Pinehouse to Regina to protest nuclear waste transport and storage. Despite advice urging him to take a break when the soles of his feet were covered in blisters and sores, he would often hit the road early in the morning before some people even woke up.

Protecting medicinal plants in the region is at the root of his involvement. “That’s why I joined the movement. When I joined the walk against nuclear waste last summer, that was my main reason for joining, [to] protect our wild medicinal plants. I’m very afraid that if some nuclear disaster ever occurred from the burial of wastes that all our plants would all be destroyed…And then where would I go from there? Where would my future generations go from there? That’s what I joined for – [to] protect our lands and resources, our herbal medicines,” says Mispounas.

Métis couple Rose and Ric Richardson also harvest medicinal herbs, berries and other plants both for their own use and to share with others. Their Green Lake café, the Keewatin Junction Station, is often a hub of activity and discussion about the future and sustainability of northern Saskatchewan. Longtime outspoken opponents of the uranium industry, they envision a northern economy based on an entirely different model of resource use.

According to Ric, organizations, government agencies, and companies come to the north proposing solutions. Outside agencies cite the high levels of poverty and unemployment in the region, while the uranium and timber industries extract billions of dollars worth of resources from northern Saskatchewan. “We live in a resource-rich area…We should be rich,” he says at the at the Survival Celebration Camp.

The Richardsons propose a model of northern development involving trad-itional knowledge and activities based on fair trade principles. They have been trying to get a non-timber forest product co-operative off the ground to process wild blueberries and eliminate the intermediary between pickers and the market. Their proposal is dependent on the protection of the land, and challenges the dominant model of northern development based on extractive industries.

The footprint of the military, oil and gas, and uranium industries continues to grow in the North, and the displacement of land-based life in Dene, Cree, and Métis traditional territories continues.

Indeed, there are some jobs, as government and industry claim. But the cost is high. The reality, as explained by Grandbois, is, “We run into big steel gates that say ‘no trespassing’ on our own territories.”