Less than two months into their majority mandate, the federal Conservatives passed legislation that left the Canadian labour movement reeling.

The Harper government’s use of back-to-work legislation to force an end to labour disputes at Air Canada and Canada Post was just the latest blow, however, to the labour movement’s most time-honoured tactic: the strike.

The use of strikes by unions to pressure employers in labour disputes has been steadily undermined in Canada in recent decades, not only by the use of coercive legislation to end – and at times pre-empt – strikes, but also by the increasing presence of transnational corporations (TNCs) with sufficient economic power to sit out strikes in a given country, or import replacement workers when local regulations allow.

In Newfoundland and Labrador – Canada’s most highly unionized province – workers have responded to the gradual erosion of the strike as an effective tool of the labour movement in a number of ways, ranging from civil disobedience and defiance of government legislation, to creative proposals to transform traditional collective bargaining structures.

In this sense, the North Atlantic’s labour movement demonstrates some of the creative ways workers are striking back against government efforts to smother their hard-won labour rights.

Domestic norms, international condemnations

Use of government legislation to interfere in or terminate labour disputes is not new, but it has been used with growing frequency since the 1980s. A 2008 study revealed 179 cases where provincial or federal governments had passed laws that interfered with bargaining rights between 1982 and 2008 (85 of those were back-to-work legislation). And the legislating has intensified in recent years.

Leo Panitch has been following this trend with interest and concern. A professor of political science at York University in Toronto, he wrote, together with Donald Swartz, what’s become a classic study of the phenomenon.

Their work puts Canada’s record in international context. Since 1981, they observe, more complaints have been filed against Canada by its unions than any other country in the world. Since the International Labour Organization’s Freedom of Association Committee was created in 1951, only four countries – Argentina, Colombia, Peru and Greece – have faced more complaints than Canada. By 1991, more than one-third of all international labour complaints against G7 countries were filed against Canada. Many of these were the result of back-to-work legislation.

Use of back-to-work laws has become so commonplace in Canada that governments and the public alike are often oblivious to the singular reputation Canada has garnered internationally by disregarding global labour standards.

Panitch and Swartz coined a term for this: permanent exceptionalism. What was meant to be an exception – legislating workers back to work – has now become the permanent norm. “The result,” says Panitch, “is a permanent dampening effect on the use of the strike.”

Defying the law

Newfoundland and Labrador’s government has used back-to-work legislation a total of nine times since joining Canada in 1949. In many cases, this legislation has been met with defiance.

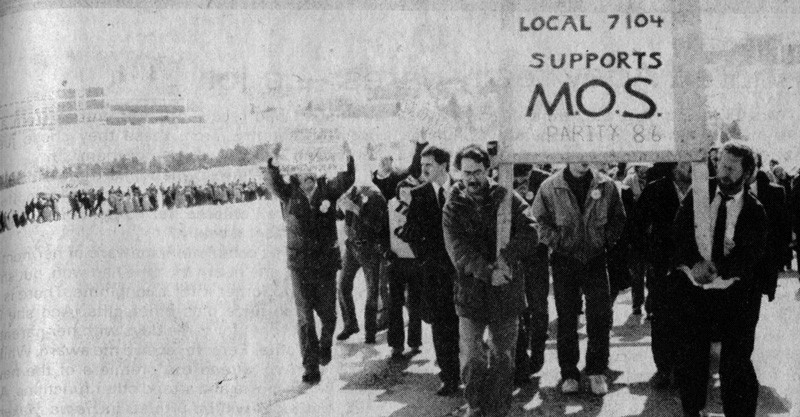

In the 1980s and 1990s, a number of union leaders, strikers and even sitting legislators served jail time for resisting and refusing to obey back-to-work and other restrictive legislation. One notable case was during a public sector strike in 1986. Passing legislation only made the strike more turbulent, as striking unions opted to defy the legislation. Hundreds were arrested, leading to justice department concerns that provincial prisons and police forces would be unable to handle the militant strikers if arrests continued.

Peter Fenwick was head of the provincial New Democratic Party and a member of the house of assembly during the 1986 strike. When back-to-work legislation was tabled by the provincial government, his party opposed it, much like the federal NDP opposed back-to-work legislation for Canada Post earlier this year. Unlike the federal NDP, however, he joined strikers in defying the legislation, knowing the act of civil disobedience could earn him a prison sentence. And it did.

“They had a prison full of public employees,” he said, reflecting on the events 25 years later. “It seemed to me that the most effective way to protest was to join them on the picket line and help turn the sentiment against what the government was doing.”

After his arrest, Fenwick was sentenced to two months in jail but was released after 20 days, remaining on probation for a year.

25 years later: a more complicated world

Lana Payne is the current president of the Newfoundland and Labrador Federation of Labour. She says today’s governments have made it tougher for unions to make the sort of principled protest that sent Fenwick to jail in 1986.

“In the past, labour leaders have defied legislation and gone to jail, but now governments have become smart. It’s not the leaders they go after; it’s the individual workers who get fined and charged. That’s a difficult scenario for unions to deal with. It’s hard for unions to expect their members to take this on individually,” says Payne. “In the good old days it used to be the labour leader who faced the time and faced the fine.”

But Payne raises another important point: being militant doesn’t just mean getting arrested on a picket line.

“There are different types of militancy,” she points out. “Brigette DePape was pretty militant, and she just stood up with a ‘Stop Harper’ sign in Parliament. She didn’t put up a picket line. Militancy can come in all kinds of forms: it can come on a picket line, it can come in the workplace. It’s about taking opportunities and being smart about the kind of campaigns that we have around strikes so that it’s not just us and the employer. How do you bring in the public and the community? How do you find other ways to pressure employers? Militancy is not just going to jail. There’s all kinds of ways to express your power.”

Expressing that power has taken a number of creative forms in Newfoundland and Labrador. During the sealers’ strikes of the early 1800s, poor sealers, masked and under cover of darkness, stormed and destroyed the boat of a merchant who was trying to force them to give up cash payment and accept credit notes for their dangerous and back-breaking work.

In 1956, union organizers rented planes and parachuted into remote logging camps, bypassing company security blockades in order to reach and unionize the workers. Organizers used every possible strategy on land, sea and air to organize labour’s power, with an enthusiasm that led a visiting Canadian labour representative to declare, shortly before Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949, that the capital of St. John’s was “the most organized [unionized] city I have ever seen.”

In 2005 the Fish, Food and Allied Workers (FFAW) organized almost two straight months of protest over policy changes to the fishery that included occupation of government offices and harbour blockades. One of the highlights of that strike occurred when a Portuguese trawler tried to cross the blockade. The blockading union vessels pursued and surrounded it, holding it at sea for four hours in what they dubbed a “fishermen’s arrest.” Combining the charged public issue of foreign overfishing with the union’s demands helped the union boost public support. Even normally conservative local media applauded the move, and ratings for wildly popular premier Danny Williams dropped to their lowest levels.

“For over 20-odd straight days, we blockaded the house of assembly,” recalled FFAW staffer John Boland. “There was a fair bit of civil disobedience. I think we probably pushed the line with a lot of it. At one time, we had seven or eight court injunctions out against us. My wife said to me, ‘One day pretty soon, when you wake up the only place you’ll be allowed to strike is at home!’

“At one point we blocked a shipping lane and had 14 ocean-going oil tankers just stranded at sea, unable to land. We had a blockade of St. John’s Harbour on the go for five or seven days.

Unfortunately a lot of people said that’s against the law, and I guess it is, but when times get tough we roll up our sleeves. If I look at the history of the labour movement, it wasn’t built on workers being nice people. Nice people were set aside and ignored.”

Transnationals: the new challenge

In addition to increasingly coercive governments siding with employers, the growing presence of transnational corporations, many of them headquartered outside of Canada, has also contributed to undermining the power of the strike.

Steelworkers employed by Brazilian mining giant Vale in Voisey’s Bay, N.L., learned that in 2009. Workers at the company’s mines in both Voisey’s Bay and Sudbury, Ont., went on strike that year, and for the Labrador workers it was a strike that lasted two years.

It was only after the Newfoundland and Labrador government launched an inquiry into the reasons for the ongoing strike that a settlement was reached. The Newfoundland Federation of Labour had denounced Vale’s use of replacement workers as a violation of free collective bargaining, and called on government to use other tools in the Labour Relations Act – such as use of mediators – to bring it to a close. When these failed to bear fruit, the government inquiry was launched.

The resulting report, known as the Roil Report, called for significant changes to labour relations in the province. It cautioned that TNCs disrupt traditional labour relations models since they have such disproportionate power compared to unions. It also recommended that government implement new rules to regulate labour relations with TNCs: mandatory arbitration boards and imposition of collective agreements where existing labour relations methods have completely failed (while protecting the general right to strike), quicker grievance hearings, and further research on the role of replacement workers, or “scabs.” But probably its greatest impact lies in giving public voice to the fact that labour relations need a level playing field.

“Roil is a very good summary of what happens in jurisdictions where TNCs have incredible power,” says Payne. “How do you change laws to ensure the rights we believe we have are still there and have the same meaning as when they were first introduced? That’s really the challenge, because the economy has changed substantially in the last three decades, but the laws have not changed to keep up with the economy as it is now, which is one with TNCs. And they are really game changers. We don’t have the same balance of power at the bargaining table when they can close a workplace down for a year and it has very little impact on their bottom line because they have operations around the world.”

Panitch finds the report’s conclusions interesting, but cautions that every situation is different. “Some have argued that with TNCs, if you strategically strike in one place, you can shut the whole operation down.”

Whatever unions do, Panitch says, they’re going to have to do it quickly. “I think the smashing of public sector unions is on the agenda. And I don’t just think it’s Canada. It’s everywhere.”

Instead of picket lines, work-ins?

In a creative article published last year, Sam Gindin, York University Packer Visitor in Social Justice, and Michael Hurley, vice-president for the Ontario wing of the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE), argued for a novel idea. As part of a wider range of tactics designed to expand collective bargaining, they suggested workers stage “work-ins.” For instance, health- or long-term care workers could pick a day to all come in to highlight worker shortages. Social workers could meet with welfare recipients to discuss their mutual frustrations with how programs operate. They note that the Public Service Alliance of Canada did this when employment insurance rules were recently tightened. They prepared pamphlets to inform recipients about how to avoid being cut off.

Such acts would improve service and demonstrate very clearly what unions have been arguing: more public service workers means better public services. Moreover, workers themselves would organize these tasks and thus start taking control of the workplace out of the hands of employers and putting it back into the hands of the workers. If employers don’t like it, their only option would be to kick out the workers, reducing the quality of service and generating public backlash against the employer – not the striking worker.

Panitch thinks the idea is one that should be taken seriously. “It raises the question not only of showing up at work, but also beginning to take responsibility for the labour process. A lot of workers don’t like to do this because they think that’s management’s job. But a work-in could show how much better services could be if there were additional staff, how many fewer accidents there would be in nursing homes, how much better patients in hospital would feel about being there, and what have you.”

Panitch feels part of the problem is that strikes have become associated almost exclusively with wages, and that’s not all of what it should be about. “It isn’t just about getting more in order to keep up your standard of living. It’s that, but it’s also an expression of frustration with regard to the lack of interest and control over one’s work. And it’s always been that. But the easiest thing to bargain is wages. It’s much harder to transform the deeply authoritarian nature of the workplace.”

Is there any point?

With governments so willing to intervene in favour of corporations, is there still any point to going on strike?

Panitch thinks there is, but warns unions need to recognize public attitudes toward strikes and be strategic in their use. “There are smart strikes, and there are dumb strikes. And you choose times that are good to strike and bad to strike. And you need to conduct strikes in such a way that you’re not alienating the populace of the city. I think even if you know that you’re going to be legislated back, if it’s part of a mobilizing strategy where it’s going to carry your members’ notions of consciousness and solidarity and understanding of the state further, it may be worth doing.”

On the other hand, he points to the CUPE municipal workers’ strike in 2009, which he feels contributed to the strengthening of right-wing sentiment in Toronto and the election of Rob Ford and other conservative candidates to city council.

Ultimately, he says, unions need to make decisions on a case-by-case basis. “I don’t think there’s ever a ready recipe for every instance. I think people do need to make sacrifices sometimes if they think it’ll have a galvanizing effect.”

Payne also feels that striking remains an important form of action for unions. “We’re facing a government that declared a war on the labour movement,” she says. “We have to keep doing what it is what we do, and always be looking for ways to step it up.”

_780_520_90_s_c1_c_c.jpg)