Ana Maria sits across from me in the empty dining hall of the hotel where she works. Starched white table cloths lay folded over dozens of square tables. Her hands cup a cloth napkin that she folds back and forth.

“It wasn’t until 2010 that I became interested in going to Canada. I was left without work and I saw it as a way to survive, to support my three daughters [as a single mother], and so I made the arrangements. Recruiters brought me to a farm to discuss going to Canada and they said I would have to wait, as there were others already in line.

“They spoke about what people in Canada did: planting, picking fruit or flowers. I had to leave a deposit. They gave us an account number, where we had to transfer the money; the only proof we had was the payment receipt of 10,000 quetzales (C$1,806).

“Recruiters would call us together for meetings at different places – in town, at the gas station, or in the homes of the organizers – and would share information that couldn’t have been true, because they always said we would travel in one month, then in another month, and another, and this was repeated until it had been over a year. It never happened. We were a big group, maybe 25 people, so imagine that, at Q10,000 each.

“Afterwards, ACADEC [another recruiter] appeared, and again I saw the potential for a better life. Here in Guatemala, when you see something that might improve your life, to live with a little more economic stability, to support your family, you take it. So I went to their offices, to a big farm where they had meetings and spoke about work in Canada.

“Everything seemed in order: we got passports, did tests, gave them all of our papers. They brought us to a clinic where we did a blood exam. We even had to pass a two-week training on Canadian farming, where they gave lectures and spoke about agriculture, how to plant and so on, giving us all kinds of information and testing us about the work we would do. We got a diploma at the end, to certify us. The training cost was Q2,000 (C$361). They said it was the price to prepare us to work in Canada. They even took our measurements for what they said would be uniforms and equipment. This also had a cost. Everything had a cost.”

Privatizing labour

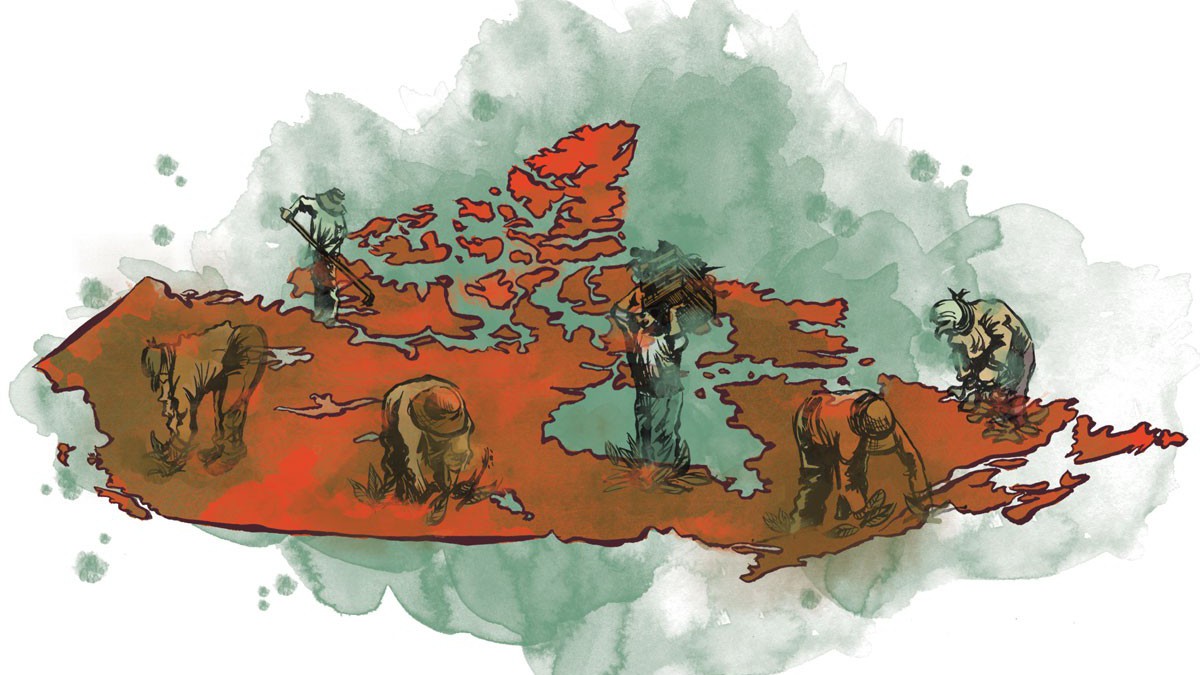

Every year, migrant workers are selected through the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) to fill more than 80,000 precarious, poorly paid agricultural, landscaping, and “lower-skilled” positions in Canada. Of those, over 6,000 workers are Guatemalans who are employed for low-waged work in Canada.

Guatemalans have become the largest incoming agricultural workforce for Quebec. The most recent statistics available show that, in Quebec alone, over 65 per cent of farms employ Guatemalan workers. However, thousands of others from that country who have paid recruitment organizations to secure their employment in Canada have never arrived.

The recruitment of Guatemalan workers to Canada has become an industry unto itself.

The sourcing of Guatemalans for work in Canada began in 2003, under a program formerly known as the Guatemala Low-Skill Pilot Project. The foundation for the program had been laid eight years earlier, when Canada signed the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), a multilateral free trade agreement that created the framework for privatizing international trade in services. GATS facilitated the deregulation of migrant worker programs in Canada, making bilateral agreements obsolete. Workers could be granted temporary entry into Canada with a Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA), which reinforced the power of employers by privatizing the insourcing of migrant labour.

In the early 2000s, the Quebec-based Foundation for the Recruitment of Foreign Agricultural Labour (FERME) began to seek out ways to hire agricultural labour from countries outside of those already participating in the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP) – specifically, from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. By 2003, FERME and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in Guatemala formally partnered to recruit workers to Canada. Their alliance marked the beginning of the deregulated TFWP.

An intergovernmental organization promoting “orderly migration for the benefit of all,” the IOM administered the recruitment and management of Guatemalan workers for Canada for a decade, until accrued corruption charges from the Guatemalan state forced it to leave the Central American country in 2013.

Even before the IOM’s expulsion, however, new recruitment organizations had already started to pop up in Guatemala: in 2009, FERME’s private recruitment counterpart in Guatemala City, Amigo Laboral, began processing the majority of workers going to Canada. Another local development organization, ACADEC, began recruiting workers the following year. In the wake of the IOM’s disappearance from Guatemala, five new recruitment organizations surfaced in 2013, profiting from the high demand for out-migration to Canada. Of the seven organizations currently recruiting labour from Guatemala, four are run by former IOM staff.

Creating precarity

Two powerful processes – one economic, the other discursive – uphold the recruitment of migrant workers.

As pointed out by social justice organizer Harsha Walia, the category “migrant worker” is created and reinforced by a system of precarity, whereby employers hire workers who will always be excluded from permanent and protected labour. Migrant workers who are categorized as “low-skilled” are tied to their employer, paid minimum wage or less, and have no channels to access permanent residency. Typically, they do not have full access to labour protections, social services, or benefits. The risk of immediate deportation acts as a barrier to organizing against their exploitation.

The TFWP model of managed migration also depends on the discursive “othering” of migrants: it is the supposed “foreignness” of workers that legitimizes their precarity, despite living and working on the same territory as Canadians.

Canadian border-enforcement practices and the apartheid of mobility are founded upon lawful colonial violence: they depend on the ongoing dispossession and displacement of Indigenous peoples, and take shape through immigration categories that divide and commodify particular groups of people, constantly positioning migrants of colour as temporary and “out of place.”

In contrast to the myth of the benevolent, tolerant Canadian mosaic, Canada’s immigration regulations have always functioned to produce precarity and impose lawful dispossession onto racialized groups: from the banning and regulation of “non-preferred” – that is, non-white – races in the 19th and 20th centuries to the creation of the first migrant worker program in 1966 (around the time that possessing particular racial criteria became eliminated as a requirement for immigrating to Canada).

Changes to the TFWP in 2014 have nonetheless placed temporary migrants under even more precarious conditions: policies such as the “four in and four out” rule, shorter stays in Canada, and increasing application costs put workers arriving through the TFWP low-waged stream in a more vulnerable – and temporary – position than ever, particularly due to the burgeoning for-profit industry that has come to comprise Canadian managed migration.

FOUR IN AND FOUR OUT RULEThe “four in and four out” rule came into effect on April 1, 2015, effectively blocking workers who have been returning to Canada for four years or more from returning to work in Canada. Workers are required to leave Canada for four years, and then may reapply to the program. This legislation further impedes workers from organizing for better conditions or being able to access social benefits and has been called “one of the greatest mass deportation orders in history” by migrant justice organizers.

Promises of a better life

Why are so many Guatemalans signing up with recruitment agencies? A milieu of widespread poverty, insecurity, and displacement in Guatemala caused by years of imperialism, state violence, and the expansion of foreign agribusiness and mining projects (with over 88 per cent of mines in Guatemala being owned by Canadian corporations) has positioned migration as a vital means of survival for hundreds of thousands of Guatemalans.

Many rural labourers migrate seasonally to coastal plantations or work in neighbouring countries – usually Mexico or the United States – as undocumented workers. As rumours of legal and “secure” out-migration to Canada have spread, however, there has been a growing demand for obtaining employment here.

Recruiters present work in Canada as an assured, safe option with “little to no possibility for labour discrimination or abuse.” Allegedly “free from risk,” the lawful structure of the TFWP is used as the basis to promote the program, as well as to justify training costs for producing the “qualified” and “disciplined” workforce required for “legal work” – despite the fact that the TFWP legally subjects workers to a system of labour apartheid, whereby workers are deportable, disposable, bound to a single employer, and denied access to the benefits and labour protections into which they pay.

The recruitment industry

Recruiters, meanwhile, hold power over work access, controlling what information is available to workers and determining what individuals must do – and what they must pay – to secure work in Canada. Requirements vary among employers and recruiters, giving rise to rampant fraud and misinformation; according to interviews with workers and agencies, many organizations demand payments simply for taking workers’ names.

Workers have reported an array of abuses from recruiters, from outright fraud and the overnight disappearance of agencies to the misrepresentation of jobs or immigration requirements, the withholding of information and documents, and extensive pay deductions.

José, a worker from Santa Rosa, Guatemala, says, “Recruitment is a bad game, because you don’t know [if you’re really getting a job or not], and you can never know if it’s true or a lie.”

Guatemalan workers have reported paying fees ranging from Q2000 to 80,000 (C$367 to $14,688), depending on the length of trainings, the desired job sector, or the level of corruption of the labour broker, with some brokers promising workers access to permanent residency once in Canada for a premium fee. Many workers who have paid these fees never leave Guatemala.

Samuel, a worker from Guatemala City, asserts: “[Recruiters] should stop charging money. People have paid too much money … brokers are charging upwards of Q25,000 to 30,000 (about C$4,590 to $5,500) just to put workers on a waiting list.”

As Canadian employers go shopping for recruiters to satisfy their labour preferences and profit margins, agencies are increasingly competing in a “race to the bottom” to send a cheap,disciplined, and specialized workforce to Canada. This leaves workers to shoulder ever-growing recruitment costs, despite the fact that, according to Employment and Social Development Canada, these costs should be covered by employers.

Canadian jobs, meanwhile, are presented as exalted positions only for the most moral, qualified, and obedient (“good”) workers. To be considered for a Canadian contract, workers must have “good moral character,” a pristine legal record, strong mental and physical health, an obedient work ethic, proven agricultural expertise, and the capacity to withstand extreme weather, as well as family in Guatemala to ensure return.

One worker states, “Agencies carry out an exam on your ability, to see how well your brain works and how your hands move…. [You also] need the mentality to go [to work in Canada], and the physical ability to do it.”

Recruitment is also overtly racialized and gendered according to sector. Recruiters classify workers according to their height, weight, age, gender, regional climate, and racial and physical characteristics.

With certain attributes requested for specific jobs, classification has come to distinguish which workers – and regions – are “more suitable” for which kinds of employment. For example, sociologist Kerry Preibisch points out that Canadian employers consider Jamaican workers more suited to fruit tree picking, while Mexicans or Guatemalans are preferred for field harvests. This plays out on a regional level as well: taller Ladino workers (Ladino refers to those of predominantly European descent or identifying as white in Guatemala) from Santa Rosa are primarily recruited for chicken catching, while Indigenous Kaqchikel workers from Chimaltenango are most commonly found in vegetable harvesting; some employers request people “from cold regions … who can tolerate the cold,” who, according to recruiters, may more easily “adapt” to Canadian seasons.

As one agency explains, “There are demands for specific kinds of people: the employer tells us that he needs someone between the age of 25 and 30, who measures 1.7 metres, for a chicken farm, so we need someone who is tall; but, if it is to cut cabbage, lettuce, or broccoli, we need someone who is shorter and a different age, and that is where worker classification comes in.”

RECRUITMENT TRAININGTraining programs based on agricultural work requirements – such as specialized agricultural training, language classes, and observational testing to evaluate workers’ capacity for compliance and diligence – have become commonplace. Three agencies run “model Canadian farms” in removed rural areas of Guatemala, where workers pay to carry out voluntary agricultural labour while being observed and trained. As described by one agency with over 275,000 members across Guatemala: “We, in a visionary way, ask workers to think that what they’re doing here [in the training centre] is what they’ll be doing in Canada…. We try to make sure that everything is in order, that everything [is done] obediently: personal hygiene, eating habits, listening and receiving orders, everything … we have people from all over Guatemala and it is growing everyday.”

With no limit to essentialized demands, employers go so far as indicate the dress, marital status, and family structure of the workers they are seeking. One agency comments: “There are farms [in Quebec] that ask that women come only from rural areas in Chimaltenango, wear their traditional Indigenous dress, be single, and without commitments.” (“Without commitments,” in this sense, typically refers to being without children or family obligations.)

The cost of a job

Many workers take out substantial loans to meet recruitment costs, borrowing from family members, banks, or labour brokers, often leaving their home or land as a collateral in the hope that they will be sent north.

One worker explains, “I mortgaged my house to be able to take a loan out at the bank because that was what the bank asked me to do. I had to have a security deposit in case I wouldn’t be able to pay, for the bank. So that the person I paid the money to [for recruitment] wouldn’t have any problems. Right now I am barely making any money … on top of loan payments, [I can’t even cover] the costs of my kids’ education and support my family.”

Workers return to Guatemala at the end of their contract without any guarantees to be rehired in Canada the following season. To be recalled, they must be “named” by their employer as a “good” worker. Recruiters then manage which candidates will return and which become permanently blocked from the program.

The blacklisting of workers is arbitrary and widespread. One recruiter notes, “We had to block 400 workers for protesting [against their work conditions].”

Workers who speak out against dangerous or racist working conditions are often singled out as “troublemakers” and deported to Guatemala. Still, according to many workers and agencies, they have been excluded from work in Canada for situations outside of their control: an early end of the season in Canada, suffering from an accident at work, or having to tend to a sick family member in Guatemala. Recruiters have cited “low productivity” and “bad behaviour” as common reasons for blocking workers from returning to Canada.

With limited options at home, Guatemalans nonetheless continue to seek employment opportunities in Canada and organize to reinstate their status as temporary workers, as seen with the Guatemalan Association United for Our Rights (AGUND), a group of blacklisted Guatemalan workers who have denounced program and agency abuses, and are fighting for the right to return to work in Canada.

Meanwhile, new recruiters continue to surface in Guatemala, promising to provide Canadian employment.

“They have always been lies”

Migration management institutions in Canada and abroad are increasingly attempting to control the mobility of “foreign” (read: racialized) peoples. Employers are satiated with access to precarious labour, while governments and migration “experts” market their discriminatory and exploitative policies as “for the benefit of all.” Meanwhile, a growing sector of for-profit agencies capitalizes on the already limited claims to movement of workers driven into debt by the hope of working in an imagined Canada.

Under managed migration, workers remain perpetually positioned as displaceable and disposable by employers, recruiters, and the Canadian state. The very structure of the TFWP creates possibilities for exploitation and deepens relations of domination, while the dispossession of workers is presented as lawful and even charitable.

As Ana Maria tells me, “This situation happens because people are desperate. You believe you’ll be able to recuperate the money you invest because obviously you can make a lot more money in Canada, salaries are better than here, and so you make deals to be able to get this money and pay for the paperwork, and be part of the group that might travel. And if you don’t have the money, if you don’t have cash, they accept loans, they accept cars, payment agreements, or you take out credit at the bank and leave your property as the guarantee. Or you turn to moneylenders, with high interest rates, who charge even more, and so you are left much more indebted, with more problems.

“My economic situation has gotten worse and so I’m always looking for ways to get some more stability, to recuperate my home, to have a more steady job, because I have three daughters, you know, that’s why I’m always fighting.

“I’m still looking for opportunities to work in Canada, but, well, they have always been lies, always. Yet here we are, thank the Lord, standing up and moving forward, each day an opportunity to rise up little by little. Perhaps I’ve been looking in the wrong places. This is what happens: you believe so deeply that you look in the wrong places.”

Several days before this issue went to press, Briarpatch learned of the passing of Dr. Kerry Preibisch. Our hearts are heavy with the loss of a courageous scholar and defender of migrant justice.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article noted that Guatemalan workers make up over 65 per cent of the workers employed on Quebec farms. This is erroneous, and has been changed to the following: “The most recent statistics available show that, in Quebec alone, over 65 per cent of farms employ Guatemalan workers.” This correction will be printed in the May/June print issue of Briarpatch.