“Fuck your unpaid internship.”

This was one of the more colourful slogans scrawled on a sign at the peak of the Occupy movement. Held up by young people who stand to lose large from financial-crisis fallout, placards like these are refreshingly frank refusals of the mantra that we must be willing to do “more for less” nowadays. A 21st-century update on Bartleby’s famous reply to the duties assigned by his boss – “I’d prefer not to” – the intern invective expresses the frustration bubbling among youth facing mounting student debt and diminishing prospects for employment.

If decent, full-time work is getting harder to come by, the same can’t be said for internships, whether unpaid or barely paid. Internships received a slew of media attention after Ross Perlin published his exposé, Intern Nation: How to Earn Nothing and Learn Little in the Brave New Economy. Less attention has been paid to the swell of activism confronting exploitative internships and the cultural conditions that condone them. From street protests to online campaigns, the emerging intern activism is one part of the wider effort by fresh actors to reformat labour politics for precarious times.

Take, for example, the Canadian Intern Association. Founded in May, the association is perhaps the first group organizing to address un- and underpaid internships in Canada. The 20-somethings who attend its meetings are swept up in the anti-internship momentum. “This isn’t something that I had planned to do for a long time,” says the association’s chair, Claire Seaborn. The idea to form an intern-rights group came to her while chatting to friends about internships over beers. “There’s been so much interest in [the association] that I’m, like, ‘OK, I guess we should just keep doing it.’”

And there are plenty of reasons to keep doing it. Mainstream mentality holds that internships are “win-win”: employers get to test drive potential recruits and have some humdrum tasks attended to; interns get to preview an occupation, gain valuable work experience, and make connections needed to launch a career. This rationale, however, ignores the power relations under-pinning the internship system.

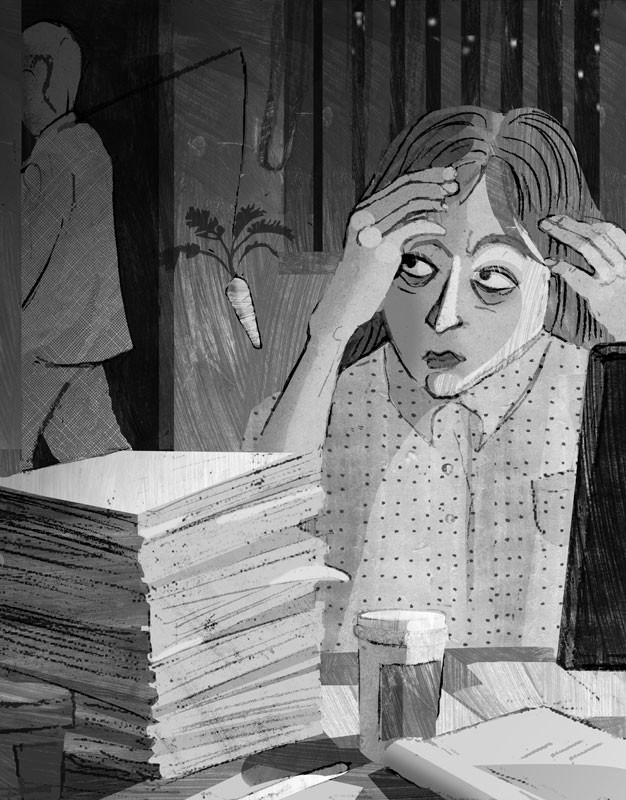

One of the many grievances piling up against internships is that unpaid interns frequently perform work that used to be done by entry-level paid staff. Interns are also denied access to labour protections and benefits extended to traditional workers. Internships may provide the proverbial foot in the door, but they come with no guarantees: a 2012 survey by the National Association of Colleges and Employers in the U.S. reveals that a slim 37 per cent of unpaid interns received job offers.

More importantly, few people can afford to work for free. If doing an unpaid internship persists as an obligatory rung on today’s shaky career ladder, the professions drawing on this system will be transformed to favour those from wealthier backgrounds. Beyond parents (not all of whom can remortgage to support their 22-year-old’s cashless gig in an expensive city), subsidies come from personal loans or part-time jobs. Internships supply a lesson not only in class inequality, but ageism, too. “Paying your dues” is a lazy cliché rather than an ethical argument for why it’s acceptable for young people to donate their labour.

Once an intern, it is difficult to take a stand against one’s exploitation. Internships effectively have gag orders built into them. No matter how distasteful their quasi-job, few interns would jeopardize the bait (graduating to full-time, a glowing reference) or annihilate their reputation for being “agreeable” by speaking out.

Interns are not only silenced, they also are invisible. Despite the growing controversy surrounding these positions, no official count of the intern population exists. Andrew Langille, a Toronto-based employment lawyer and vocal critic of unpaid internships, estimates there are about 200,000 in Canada. But it’s a handful of intern celebs that attracts most attention: Kanye West interned at Italian fashion label, Fendi; Lady Gaga with Irish hat designer, Philip Treacy; The Hills’ Lauren Conrad at Teen Vogue. This glamorous cast is unlikely to discourage applications to intern in the media and cultural industries, which, critics charge, are the worst culprits of intern injustice.

On a recent CBC Radio program, a former music industry intern said her tasks included “cleaning bathrooms.” It’s an attention-grabbing vignette, and one that challenges the increasingly unhelpful myth that interns merely shuttle caffeine to higher-ups. It also undermines companies’ claims that interns mainly obtain career training and therefore don’t merit a paycheque. Interns do a wide range of valuable work that companies normally pay workers to do. A survey by the U.K. National Union of Journalists found that nearly 80 per cent of journalism interns who published content while on a work experience program were not paid for it. When unpaid interns do revenue-generating work in the arts, media, and culture, corporations are cashing in on young workers’ passions. “Just because [someone] likes to design, doesn’t mean they shouldn’t be getting paid,” says Seaborn.

Interns strike back

Working gratis to wipe down a urinal is a far cry from the glamourized activities of the “creative class.” Disenchanted interns are fighting back. Groups tackling exploitative internships have sprung up internationally over the past few years: Intern Aware in Britain, Intern Labor Rights in the U.S., Génération Précaire in France, Repubblica degli Stagisti in Italy, and Hague Interns Association in the Netherlands, for example. Current and former interns and their allies track intern issues online through Twitter accounts, Facebook pages, and blogs like Canada-based Internsheep and Youth and Work.

Intern activists point to a galloping youth unemployment rate, a super-competitive labour market that pressures job seekers to one-up each other, and the tendency of unpaid internships to replace entry-level openings. That current and former interns are speaking out also reflects a political shift. “We are coming out of a period of intense neoliberalism and a retrenchment of the social welfare state,” says Langille, “and people are getting more comfortable fighting battles involving labour.” Occupy is an obvious example. “There’s a generation coming into the workforce that’s never been in it before,” adds Langille. “And I don’t think they’re liking what they see.”

Litigation is one tactic activists are using. A common critique of internships is that interns are misclassified: employers designate someone an “intern” but assign them work otherwise performed by a paid employee. American media companies engaged in this practice are now in the spotlight as defendants in class-action lawsuits, including suits against magazine publisher Hearst Corporation and Fox Entertainment Group. “These court cases are absolutely necessary,” says a participant of the New York City-based Intern Labor Rights. “Once [companies] realize that their bottom line is at risk, their attorneys are going to say, ‘you can’t do that anymore.’ And there will be a sea change.”

Legal challenges have had some success in reclaiming wages. In the U.K., the National Union of Journalists, through its “Cashback for Interns” campaign, helped win a 2011 case for a 21-year old ex-unpaid intern whose eight-hour days included the supremely ironic task of “hiring new interns.” If the cost of legal proceedings and settlements threaten to exceed that of simply paying interns minimum wage, the media industry’s intern party just might wrap up in a courtroom.

Given this, it’s not surprising that the Canadian Intern Association was founded by a law student and that young media workers have made a strong showing at the group’s meetings. In Ontario, where the association is based, there are no regulations covering unpaid internships per se. However, the province’s Employment Standards Act does set out criteria that companies using “trainees” must follow. It explicitly states that internships must benefit interns, not employers. “If [the criteria] are not met,” says Seaborn, “then the intern should be getting minimum wage.”

Even so, many interns are more interested in making a good impression than consulting employment regulations. The Canadian Intern Association wants to “raise awareness” about existing regulations and “enforce the law.” Such a mandate generates the rather paradoxical scenario of a group of volunteers doing the job of government employees, extending even further the range of work outsourced to interns.

Seaborn describes the Canadian Intern Association as an advocacy group that views employers as potential partners in the effort to improve internships. Eventually, she wants the association to prepare a best-practices internship guide and offer a “stamp of approval” to companies that play fair. Although it strategically avoids an adversarial stance, the Canadian Intern Association is not antithetical to a union ethos. After all, Seaborn says that the project sprang from the idea of “organizing a group of people that are currently not organized.”

And interns are extremely challenging to organize, not least because they are dispersed across so many worksites and fill fleeting positions. School is one place, however, where past, current, and future interns congregate in droves. Colleges and universities are becoming a strategic site for organizing. Campuses are a decisive institutional link in the unpaid labour chain: career centres advertise dubious unpaid positions at for-profit companies, academic programs charge tuition fees for credits earned through unpaid placements, and teachers, as an Intern Labor Rights activist puts it, advise their students, “Oh, what you need to do in your summers is intern.”

It’s encouraging then that the Canadian Intern Association received a formal expression of support from the executive of the Ryerson Students’ Union (RSU). Melissa Palermo, vice-president of education for the RSU, sees the collaboration as a natural alliance since the job of a students’ union is to“advocate for students” who face a triple challenge: rising tuition fees, rising debt, and rising unemployment. As Palermo notes, the internship issue is especially acute for students in communications, fine arts, and design programs. At the provincial level, the Canadian Federation of Students-Ontario passed a motion in August condemning exploitative unpaid internships.

Naming and shaming

Intern activism bears the marks of the precarious conditions in which interns find themselves in distinct ways. Activists emphasize the importance of sharing personal experiences of exploitative internships, but the emphasis on exposure goes hand-in-hand with a need to preserve interns’ anonymity. The masks worn by members of the Carrotworkers’ Collective of London, England, underscore the point. As an Intern Labor Rights participant says, “The reputational risk is so high for someone to speak out.”

Even under the cloak of anonymity, many groups take a confrontational approach, such as publicly “naming and shaming” companies that post unpaid internships online. In addition to producing its Surviving Internships: A Counter Guide to Free Labour in the Arts, the Carrotworkers’ Collective has been involved in street-level protest against austerity.

The group has attended demonstrations dangling carrot sculptures – the “carrot” in question being the promise of autonomy in creative work – and carrying signs with messages like “internship = infinite free labour.” Over the next year, the Intern Aware Street Team will hit the streets of London, holding flashmobs and pulling stunts outside businesses that hire unpaid interns.

Intern Labor Rights, a subgroup of Arts & Labor, which grew out of Occupy Wall Street, has put forward a straightforward ethical injunction – “Pay Your Interns!” – which they have silkscreened onto T-shirts. In its first intervention, the group sent a letter to the New York Foundation for the Arts requesting that it stop posting unpaid internships at for-profit companies on its job board. This summer, it took its message to the streets, descending on Times Square to chat with New Yorkers about unpaid internships in the creative industries and beyond.

Canaries in the coal mine

As one member of Intern Labor Rights sees it, the tendency among young, aspiring cultural workers to devalue their own labour is a challenge to the growth of intern labour activism. “This generation doesn’t even look at it as exploitation,” this member says. “I don’t know how a bunch of smart, highly educated, willing workers can walk into an office or onto a film set or into a gallery, contribute all that intelligence, energy, and enthusiasm to an organization [and its] bottom line, and then think they didn’t have anything to contribute because they [haven’t] already worked in the industry for five years…This whole idea that their contribution doesn’t mean anything yet, has no value, they’ve completely internalized [it]. It’s horrifying to watch.”

Which makes this surge of intern activism all the more inspiring, especially at a time when making connections on LinkedIn is often the closest one gets to collective action in the labour market. These groups arise from the realization that it’s not personal failings but systemic forces that make a meaningful, sustainable livelihood so elusive. And that if you want to make a change, you can’t do it alone.

These initiatives mostly bypass the aging unions that have had difficulty or no interest in engaging young people. Youth-led groups are reviving interest in issues at the heart of the labour movement: corporate exploitation, economic justice, and social protection. What’s more, they are experimenting with ways to mobilize and support people beyond the shrinking base of the established unions.

A partnership between the U.K. Trades Union Congress (TUC) and the National Union of Students (NUS) to tackle intern rights issues in Britain is a promising sign of collaboration. In February, the TUC, which represents 54 unions and over six million workers, partnered with the NUS to launch a year-long campaign to advocate for fair treatment of interns. The TUC developed a free smartphone app that informs users about interns’ legal rights, provides social media updates from advocacy groups, and helps calculate wages owed.

Intern-focused advocacy is a step forward for labour politics. If these groups’ gains ultimately result in compelling governments to more rigorously enforce existing regulations or in shaming individual companies into implementing “ethical” internships, meaningful progress will have been made. But an opportunity will also have been missed to name and act against a wider problem.

Unpaid internships are not an isolated issue. They’re one of many forms of free labour flourishing in the most celebrated quarters of the creative industries: citizen journalists contribute photographs, articles, and commentary to large, private news organizations; unpaid reality television participants replace paid actors on scripted programs; and professional writers work for free for large, profitable corporations. The cumulative effect of serial internships and zero-wages is the devaluation of labour, wage depression across the labour market, and the acclimatization of a generation of indebted workers to hustling from gig to gig with few expectations of their employers.

Unpaid work has emerged as a flashpoint issue for activists. Consider a handful of U.S. examples. The group W.A.G.E (Working Artists and the Greater Economy) is fighting for artists to be paid for gallery shows in more than just “exposure.” The Model Alliance is calling attention to the fashion industry’s habit of paying models in clothes. Pay The Writer!, a campaign run by the National Writers Union, is challenging non-payments for writers on sites like the Huffington Post. The Freelancers Union is pressing for an Unpaid Wages Bill to aid freelancers whose clients don’t pay up.

The time is ripening for a cross-sectoral campaign against unpaid work that includes internships, but also is larger than internships. Much larger. Under capitalism, all workers endure the problem of unpaid labour, or those parts of our days, weeks, or lives that generate economic value but for which we receive no payment in return. So although interns are canaries in the coal mine of the austerity economy, the message of the intern activists, boiled down, has 99% relevance: Don’t be undersold.

Enda, Nicole, and Greig are collaborating on a research project on labour politics in the creative industries – www.culturalworkersorganize.org.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)