In December 2015, Tings Chak stood among protesters outside the Toronto Police Service’s headquarters, holding a banner that read, “NO STATUS CHECKS IN A SANCTUARY CITY.” The protest – organized after an access-to-information request turned up thousands of police checks that sought to verify immigration information with border officials – was meant to draw attention to violations of Toronto’s sanctuary city policy.

A sanctuary city is one in which residents are able to access city services without being asked about their immigration status and without fear of being detained or deported. In Toronto, where an estimated 200,000 residents do not have immigration status, city council voted in 2014 to set out a plan for the policy, also known as Access Without Fear, after years of campaigning by groups like No One Is Illegal and the Solidarity City Network. The policy says all residents should have access to city services including emergency health care, food banks, shelters, recreation centres, and parenting programs. But the promised sanctuary has proven difficult to implement in the shadow of federal immigration laws. When undocumented migrants in Canada are found to have overstayed their visas, they are held in maximum-security facilities and detention centres – often indefinitely, without charges or trial.

As a Toronto-based organizer and artist with formal training in architecture, Chak has explored the issue of migrant detention through street-based action, graphic design, art installations, and architectural critique. Chak joined No One Is Illegal before Toronto was officially declared a sanctuary city. To Chak, status checks are part of the same practice as carding, “where police are particularly targeting people who are Black and brown, who speak with an accent, who might be immigrants or people who may be undocumented.”

Speaking to me from an artist residency in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Chak says she doesn’t think of her roles as artist and activist in the same vein. While she finds that public demonstrations often seize on a political moment out of necessity, her art practice is about creating visibility in a different way. In her artwork, Chak approaches the issue of migrant detention using architectural tools. She recreates spaces that are otherwise off-limits to the public, rendering visible the difference between sanctuary and prison – two adjacent spaces that are also diametrically opposed.

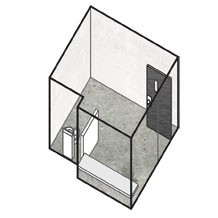

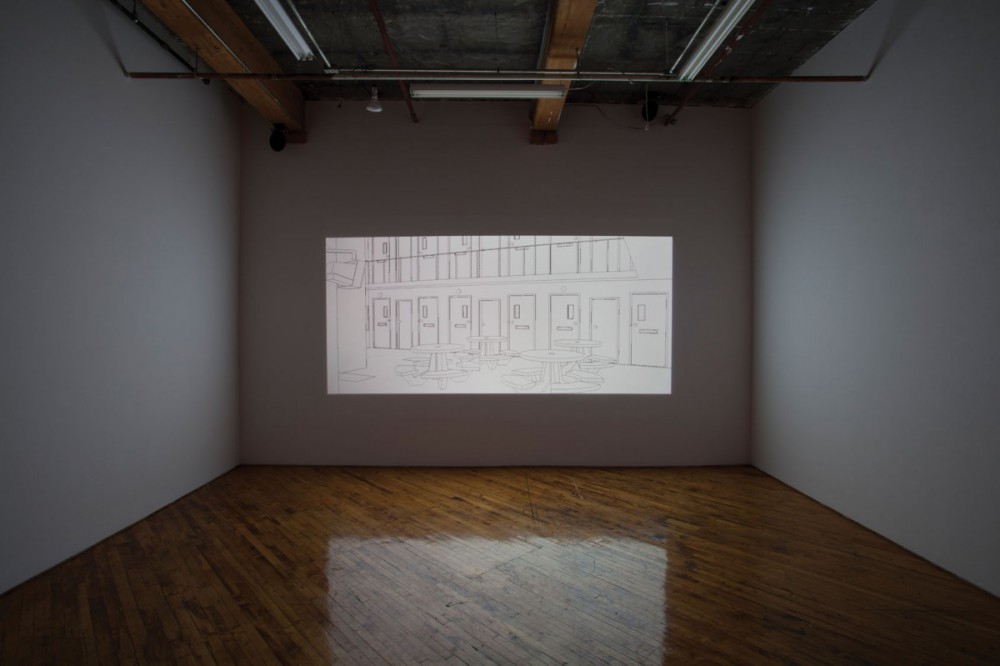

In 2015, as part of the exhibition and publication Voz-à-Voz, curated by the artist organization e-fagia, Chak created Habitable Space, in which the structures of a fictionalized detention centre are laid bare. In the six-minute video, recordings of detainees’ phone calls overlap to create an indistinct voiceover as the viewer goes through an animated tour of the facilities. Speaking over each other, detainees give their first and last names, and explain how they came to be detained. The experience leaves the viewer with a fragmented knowledge of where they are in relation to cells and corridors, uncertain as to the extent of what is visible.

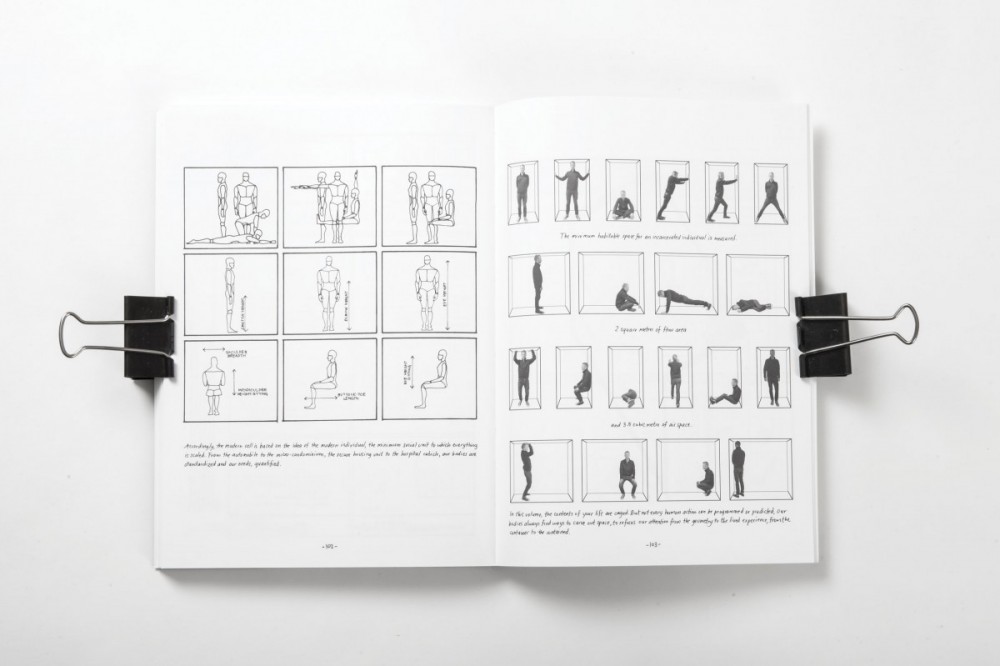

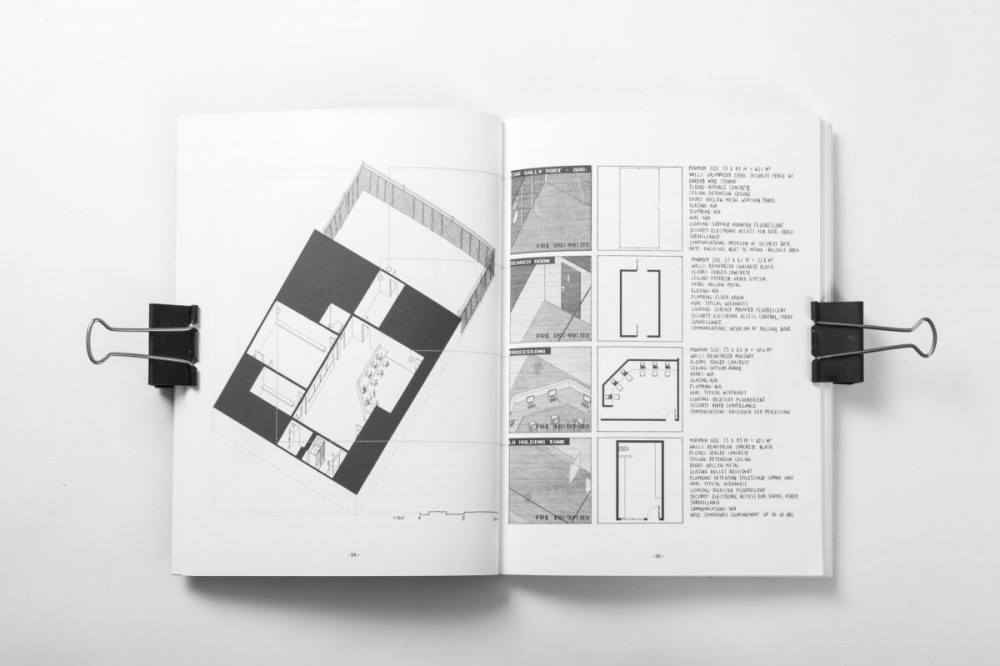

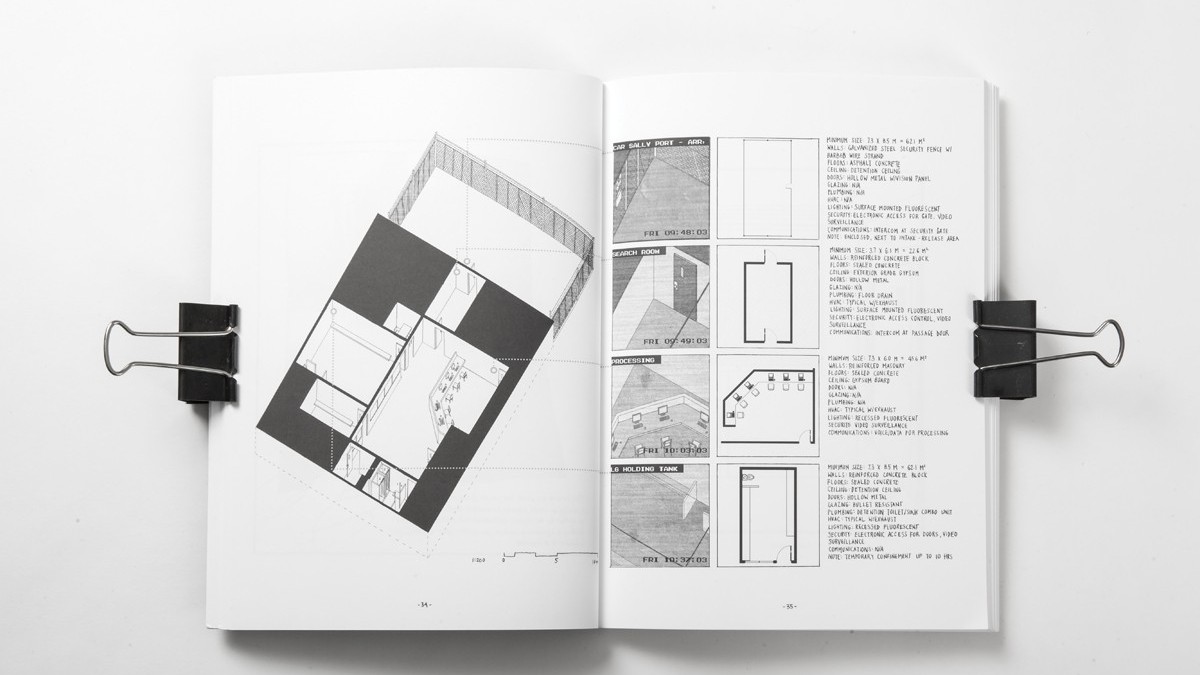

The evasiveness of the full prison complex is a prominent theme in Chak’s work, particularly in her 2014 graphic novel, Undocumented: The Architecture of Migrant Detention. The process of creating the graphic novel – a misnomer, Chak adds, because she sees it more as a work of non-fiction and a tool for organizing – was difficult from the beginning. With limited access to prison facilities as a visitor, Chak drew from prison design standards as well as conversations with detainees’ lawyers. She created a document that unpacks how design enforces control, and looks at how a space where only the most basic amenities for survival are provided can exercise violence.

“Over the year and a half or so since Undocumented has been published, it’s allowed me to enter spaces I previously didn’t have access to, to talk about the issues of detention and prison abolition, but framed slightly differently,” Chak says, “whether it’s framed as a comic book, or as a work of graphic design — or as legal advocacy when talking to law students, and as ethics when talking to architects and designers.”

The minimalism underpinning prison design is a quality of incarceration of which Chak is sharply critical. “I think the logic of the minimum is pervasive, whether we’re talking about tiny alleyway homes or prison cells, which we don’t usually put side by side,” Chak says. “It’s a logic that says human needs and lives can be quantified and reduced to metrics, to data, and to a certain square footage. I think what that does, and what architecture participates in, is moderating violence rather than questioning the violence of the system itself: if we can recreate minimum standards, then that’s ‘humane.’”

In 2013, detainees at Central East Correctional Centre in Lindsay, ON, went on a hunger strike in protest of the conditions in which they were being held. At the time, Chak was finishing her master’s degree in architecture and was working on her thesis, which would become Undocumented. Chak had been searching for a connection between what she was studying and her grassroots organizing work. She was actively involved in political organizing through the End Immigration Detention Network, fielding phone calls from detainees at the Central East Correctional Centre and building public support for detainees. In her classes, Chak found that the few discussions on the architecture of incarceration were limited to improving or reforming prisons through design, whereas she wanted to talk about abolition.“There was no opportunity to really talk about questions of prison abolition or abolition of detention, because architects are concerned with improving conditions, creating ‘humane’ spaces, or saving the day, you know?” Chak says. “[Undocumented] was a big experiment. I actually stopped working in studio because there wasn’t the political or critical space to do this work – I just worked from my bedroom and stayed there for a long time. It’s very hard to get aspiring architects to imagine the ‘solution’ to be the absence of a building.”

Chak uses architectural tools not to propose “more ethical” prisons, but to critique the system in place. “I think the criminal justice system places a lot of emphasis on the deficits of people, as do psychiatric and medical models – that people be reformed or rehabilitated rather than think about their access to social services, mental health supports, or community. The system criminalizes and ‘deters’ migration rather than questioning why people are displaced in the first place and how Canada is complicit. Rather than constructing prisons and detention centres, we need to focus on building access to dignified means of life and all the things you need to survive as human beings.”

“It’s not a broken system to be fixed,” Chak says. “I think this message has been communicated in different ways – whether it’s through a loudspeaker on the streets or through images and text – and choosing images for me is also a way to think about how to make the message hopefully broader, more accessible.”

_780_520_90_s_c1_c_c.jpg)