Plain language summary (What is this?)

- Anyone advocating for disability justice must include safe supply in their demands. Safe supply means access to legal and pharmaceutically pure versions of drugs like heroin, cocaine, or methamphetamine.

- Tens of thousands of people who use these drugs have died from overdoses. But most of the harms we see with these drugs do not come from the drugs themselves. Instead, they come from the drugs having been made illegal, which has created a dangerous and uncontrolled trade in drugs where the user has no way of knowing what is in them. It is also because this creates a class of drug users who must use drugs in unsafe locations and in unsafe ways.

- There is a big overlap between 1) communities of poor people and people of colour who use illegal drugs and are most heavily punished for it, and 2) the community of disabled people, who may also be denied legal versions of the drugs they seek because of discrimination by doctors, nurses, and pharmacists.

- Safe supply is also a disability accommodation. For people who are physically dependent on a drug, the drug is essential for their ability to function and be “well.” Research and experiences in different countries show that when people are able to access safe versions of opioid painkillers, stimulants, and other drugs for medicine or for recreation, they lead healthier lives and experience fewer of the many injustices that result from having to resort to the illegal market.

You need X. With X, you can live what passes for a normal life in these not-especially-normal times. You can eat, and you can love, and you can work, and you can think, and you can go to the pharmacy, or the grocery store, or to visit a friend, or to help a neighbour. But without X, you are adrift, deeply ill, completely incapacitated. Without glasses, myopia turns the world into a blurry clutter of unreadable signs and unreadable faces. Without crutches, a broken leg or chronic pain turn a simple stretch of sidewalk into an untraversable expanse. Without insulin, diabetes quickly parches and destroys you. Conversely, when these needs are satisfied, we are able to participate to our greatest potential, to live lives without unnecessary struggle, to have similar chances as our fellow humans. We are no longer “vulnerable populations,” a description that seems fixed but which is in fact mutable and dependent upon policy choices.

Without opioids, those of us who are dependent on them – whose bodies no longer adequately produce the endorphins that make our intestines work and our emotions balance – cannot cope. At this point, the drug becomes something that the body requires in order to maintain a steady and healthy state – this is why “getting well” is slang for taking opioids to stop withdrawal symptoms. Without the drug, you are physically and emotionally sick, to the extent that the activities of daily life are impossible, as if you were totally incapacitated by a stomach bug or the hit-by-a-truck feeling of influenza. Fundamental aspects of physical function that are normally managed by the body’s self-produced version of morphine – endorphins, or “endogenous morphine” – do not happen.

You can eat, and you can love, and you can work, and you can think, and you can go to the pharmacy, or the grocery store, or to visit a friend, or to help a neighbour. But without X, you are adrift, deeply ill, completely incapacitated.

While the legal status of drugs has changed dramatically over time – heroin was first marketed by pharmaceutical giant Bayer, for example – this truth of the drug’s effect hasn’t changed. But one’s ability to access a safe and constant supply of this drug that – for someone dependent on the drug – determines healthy function is dependent on the drug’s legality, its cost, and one’s identity. One’s ability to choose to simply stop being physically dependent also depends on one’s history of trauma, physical comorbidities, and socio-economic status. Despite societal pressure toward abstinence no matter what, the advisability of abstinence is impacted by these things too, given the heightened attendant risk of overdose and the return of underlying pain or trauma symptoms.

“Safe supply” of illicit drugs is a concept that has recently moved from a fringe, radical idea to a term bandied about by politicians, journalists, and drug user organizers alike. In fact, the Canadian government – under pressure to decriminalize and regulate illegal drugs, as thousands of people die each year from the toxic drug crisis – has announced its intent to move forward with safe supply programs and pilots. Meanwhile, B.C. has announced a plan to decriminalize the possession of very small amounts of drugs – which has been criticized by advocates as inadequate. Here, I’d like to argue that access to a safe (or, technically, safer) supply of psychoactive substances must be a basic demand of disability justice. And rather than hard-to-access, geographically limited safe supply programs, we need countrywide legal regulation.

Who is punished for using drugs?

Disability justice is a concept developed in 2005 by the San Francisco-based Disability Justice Collective, which is made up of disabled and queer women of colour. It was a reaction to their exclusion from disability rights theory and activism, and it is based on 10 principles that include anti-capitalism, intersectionality, and collective liberation. All of these points are relevant to the idea of safe supply, but in particular we might look at intersectionality, a concept and term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989. Intersectionality is the insight that multiple forms of oppression intersect in the same individual and cannot be considered in isolation – for example, Black women are oppressed in a unique way by both misogyny and anti-Black racism.

Those most at risk of overdose from illicit drugs are poor people, Indigenous people, sex workers, women, queer people, people of colour, and people who are homeless or in highly precarious living situations. These same people experience the most inadequate health care for both addiction and pain – which means that the impact of drug use on their health is exponentially worse than the intrinsic harms of the drugs themselves.

By contrast, wealthy white men enjoy privileged access to the exact same substances, which can be acquired with little fear of legal, social, or health repercussions.

People who use illicit drugs (PWUD) often try to moderate their drug use, practise harm reduction, and protect their health (including by avoiding the destabilizing experience of withdrawal), but the systems they encounter – medical, legal, carceral, and social welfare – rarely support them in this and often promote harm. By contrast, wealthy white men enjoy privileged access to the exact same substances, which can be acquired with little fear of legal, social, or health repercussions – sometimes through access to the “white market” of pharmaceutical equivalents and sometimes through differential enforcement of drug laws or laws governing access to public space.

For all these reasons, drug user rights – the right to access equitable health care, equitable civil rights, and a safe supply of drugs like opioids and other currently illegal substances – should be considered an element of disability justice, with safe supply itself a disability justice demand of particular urgency. We might then see legal regulation as a way to ensure that access to safer supply isn’t restricted to white, moneyed drug users, while other people who use drugs must play Russian roulette every day. By legally regulating all currently illicit substances (illicit amphetamines, for example), they will become subject to the same laws governing purity and reliability as other medications (such as prescription amphetamines or prescription painkillers) or recreational substances (such as cannabis or alcohol). Their marketing and sales can be controlled in the interest of public health, while eliminating the vast illicit drug industry. All told, safe supply would prevent the compounding effects of the harms that result not from the substance itself but from their illicit nature and the criminalization of those who use them.

There’s a great deal of overlap between communities of illicit drug users and disabled people. In fact, among people who use illicit drugs and suffer significant oppression, co-occurring physical and psychiatric disabilities are more common than not. This same group of people includes many people with diagnoses like PTSD or complex PTSD, depression and anxiety, learning and attention disorders, chronic pain, mobility issues, or immune suppression. Among homeless people who use drugs there are also high rates of traumatic brain injury (TBI) – for example, a 2014 study of homeless men at one Toronto shelter found that nearly half of study participants had TBIs, mostly sustained before they became homeless.

All told, safe supply would prevent the compounding effects of the harms that result not from the substance itself but from their illicit nature and the criminalization of those who use them.

Thus, the PWUD or PWID (people who inject drugs, the most highly stigmatized and multiple-oppression-facing group among people who use illicit drugs) population fundamentally is a disabled population. The Canadian Human Rights Act actually already considers substance dependence to be a disability that warrants accommodations from employers – although apparently not for the same reasons of disability justice for which I’m arguing, but rather from inaccurately conflating physical dependence or simply substance use with addiction, which is in turn incorrectly conceived as a chronic, relapsing brain disorder. In a resource for employers called Impaired at Work – A Guide to Accommodating Substance Dependence, the Canadian Human Rights Commission encourages employers to “recognize the signs” of substance dependence, which include a bad attitude and poor job performance. In reality, poor job performance in this case may well be the immediate result of withdrawal and lack of access to a drug that is necessary to the person’s basic psychological and physiological function and sense of self.

As a result, in Canada, large proportions of the PWUD and PWID populations interact with mental health in-patient and outpatient programs; with police, parole officers, and judges; with unregulated addiction treatment programs like Narcotics Anonymous; and with social welfare programs like provincial disability support programs.

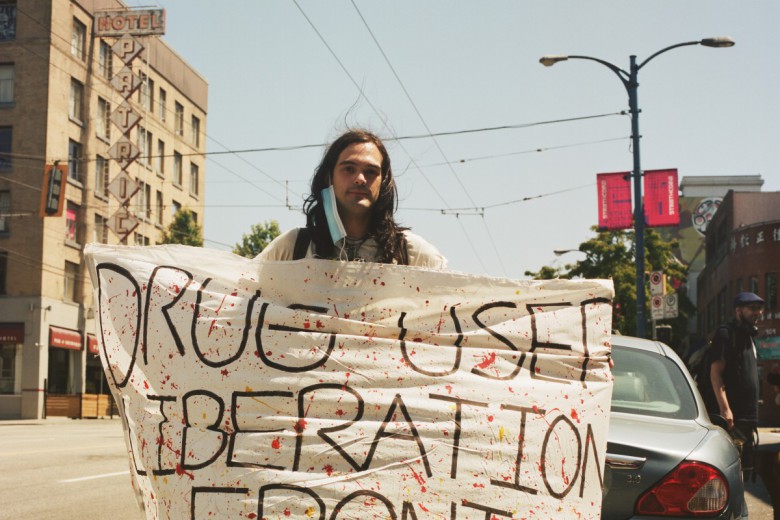

Stop fucking killing us

Increasingly, drug user activists and people working on disability justice are recognizing the overlaps. Take three Vancouver activists – Gabrielle Peters, a disabled writer and policy analyst, Tonye Aganaba, a disabled artist and musician, and Garth Mullins, a drug user activist and host of the Crackdown podcast – who have formed an informal group called the Stop Fucking Killing Us Committee devoted to organizing on issues affecting both groups.

“We’re sort of united in death,” Mullins tells me, “and that’s the intersection that I’ve really noticed.” Mullins met the other two activists when he got involved in the fight against Canada’s Bill C-7 on medical assistance in dying as well as activism around the abandonment of disabled people that occurred during the devastating 2021 heat dome in British Columbia.

“I see oppressed people […] as having common cause,” he continues, “because we have mutual interests and you can fight stronger when you’re together.”

“We were just seeing that the state, by intention or abandonment or policy or whatever, it’s just like in full necropolitics mode,” he recalls. “Killing people, like from climate change … or from toxic drug policy… or from something like Bill C-7.”

"Drug users and disabled people share the common history and ongoing threat of eugenics. [...] Our past, present and future are intertwined.”

Collaboration between drug user movements and disability justice movements is still in its early stages. But when vast numbers of people, predominantly disabled people, are dying preventable deaths from a toxic drug supply, a poorly managed pandemic, climate change, and the expansion of medical assistance in dying, the connections become clear.

In an email interview with me, Peters writes, “Drug users and disabled people share the common history and ongoing threat of eugenics. [...] Our past, present and future are intertwined.”

She notes that the line between patient and drug user is blurred by the realities of intersecting oppressive attitudes and policies. For example, Black pain patients have long been denied painkillers out of fear of addiction or the false belief that Black people feel less pain. The huge numbers of overdose deaths we have seen since roughly 2014 result in large part from the recent heavy-handed response to the opioid crisis: many people who used legal opioids for recreation or self-medication (as well as others simply taking their own prescribed opioids for pain) were stigmatized or abruptly cut off these safer alternatives, and sometimes moved on to heroin and then illicit fentanyl. “When pain medications first started to be cut back,” Peters explains, “I saw some pain patients saying that we were the ‘good ones’ who were being unfairly harmed by being grouped in with criminals. In order to participate in that kind of advocacy you had to ignore a lot of history, injustice, racism, and the way these laws are used for social control. You had to support the criminalization of other disabled poor people. And, I suppose, [you had to] trust or hope that you would never end up in the wrong pile.”

Peters argues that the disability community has much to learn from the drug user community, including “the development of harm reduction, the practice of community care, and the way the drug user community successfully managed to maintain a grassroots politic even when engaging with the system. It was, frankly, refreshingly grounded activism compared to the corporate and middle-class personality of much of disability advocacy. Many people who use drugs are disabled people who have been shut out of disability activism by respectability politics.”

Indeed, she reports, Mullins told her that she was the first person to invite him into a ‘crip’ movement. Mullins is legally blind, has albinism, and is dependent on methadone.

“Until we make sure that people – all people, no matter their status, no matter what they do for work, no matter their abilities – have access to what they need, it is criminal to continue criminalizing people for using drugs to survive this capitalist nightmare.”

Like Peters, Tonye Aganaba uses legal pharmaceutical drugs, in their case, to manage multiple sclerosis. But before that, they used similar illicit drugs in a way they say was “problematic.” Though they no longer face criminalization for using illegal drugs, they still come up against persistent anti-Black racism in accessing their prescribed, legal medication. Very similar issues thus play out in legal and illegal, medical and recreational arenas.

“As an abolitionist and as a person who has a disability, as a person who has struggled with problematic substance use in the past, it would be out of sync with the principles of disability justice not to, first of all, cross-movement organize with folks who have a seemingly disparate struggle but are of us,” they say. “Until we do what we need to do in order to make sure that people have access to the life-affirming support systems, system support, and care resources; until we make sure that people – all people, no matter their status, no matter what they do for work, no matter their abilities – have access to what they need, it is criminal to continue criminalizing people for using drugs to survive this capitalist nightmare.”

Indeed, whether a person is using drugs for recreation and feeling good or to have energy to get up in the morning or mental peace to sleep at night, or to treat a medical condition, or to cope with post-traumatic symptoms – this is an issue of what people need.

The harms of prohibition

There are many reasons to consider people who use drugs, and who also experience oppression on the basis of class, race, and gender, as a constituency that suffers most under capitalism. Modern capitalism has grown up alongside the prohibition of various substances and so can’t be understood without the legal and carceral structures that support it. Even so, anything relating to drug user rights and safe supply remains a tough sell among ostensibly progressive people. This is largely because the efficacy and safety of 12-step and other abstinence-based and in-hospital addiction treatment options has been misrepresented; because abstinence is deeply and falsely associated with cleanliness and drug use with dirtiness (mainly for poor and racialized people); and because illegal drugs are perceived as dangerous and morally bad, which in turn results in classist and racist associations and incorrect attribution of harms associated with drug use. We have a lot to unlearn.

It’s long past time for the left to recognize that disability justice requires us to attend to the vast harm that prohibition policies have caused for over a century, and, in the face of a crisis of overdose deaths and related harms, to call for safe supply and legal regulation of drugs.