Peter* carries gifts from his mother wherever he goes, keeping them especially close since her passing a few years ago. They’re by his side when he rides the metro, checks into an overnight shelter, or sleeps rough in the Henri-Bourassa Metro station in Montreal.

Travelling with his mom’s gifts can be cumbersome and, occasionally, he’s accepted a ride from the police to make commuting easier. The rides were uneventful, until about a year ago when an officer became violent and assaulted Peter, leaving him with severe long-term injuries. Reflecting on the incident, he broke down in tears. Since that day, Peter’s been wary of the police and has tried to avoid run-ins.

Every year, hundreds more people become houseless as landlords increase rents and policymakers fail to regulate. In response, in 2021, the City of Montreal launched the pilot project ÉMMIS (Équipe mobile de médiation en intervention sociale), a team of social workers the city describes as an “alternative to police intervention,” and in 2023, the city made ÉMMIS permanent, increasing the staff size, the number of boroughs in which they operate, their operating hours, and their budget to $10 million for 2024.

But just how effective is ÉMMIS at addressing its mandate of “increasing public feeling of safety?” Is it truly an alternative to the Montreal police or merely another arm of the force?

What is ÉMMIS?

“The City of Montreal decided in 2021 to implement [ÉMMIS] to go above and beyond by being present in the field to do their social intervention work,” explains Alexandre Lelièvre, a commander in the Service de police de la Ville de Montréal’s (SPVM) urban prevention and security division. “This social intervention work is often placed on police officers, but police officers are just that, police officers [...]. Before ÉMMIS, [this work] was not the responsibility of a single institution.”

Now, instead of Lelièvre or one of his fellow officers responding to “non-urgent, non-criminal” cases, the force is supposed to forward them to ÉMMIS so the project can respond in a way that keeps “vulnerable people out of the legal system” while “improving social cohabitation among different groups.” ÉMMIS also responds to requests from merchants, residents, community organizations, municipal services, and boroughs “involved in a social cohabitation issue.” The project doesn’t list a phone number on its website, only an email address, but local businesses and housed residents in the boroughs where the team operates have been given ÉMMIS’ number, says Guillaume Rivest, a City employee.

A typical day for ÉMMIS interventionists Noure* and Frédérique* begins with partner and case assignments and reviewing goals for the day, which can include checking in with business owners, following up on existing cases, and patrolling assigned boroughs looking for people in crisis.

Over 4,500 people were visibly unhoused in Montreal in October 2022, 33 per cent more than in 2018.

Every pair has a van equipped with “CPR pocket masks, condoms, pads and tampons, aluminum blankets, and tissues,” Noure explains. On board there’s also a defibrillator, extra clothes, first aid supplies, and pen and paper, so any important information can be given to the person ÉMMIS interacts with.

“The most important thing in our bags is Naloxone because the possibility of coming across an overdose always exists,” says Frédérique. “In the winter, we also carry socks – that is something we get asked for a lot. We have first aid kits with bandages, antiseptic pads for people who are hurt, and what is really important is to have a bucket for needles because we pick up any we see.”

ÉMMIS agents follow up on non-emergency cases like transporting a person from a shelter with no available beds to another or checking in on someone they know has been camping in a Metro station doorway because they feel unsafe in a shelter. Other days, agents are responding to more urgent cases, like overdoses, and driving anyone experiencing a medical emergency to the nearest hospital. Since its creation in 2021, ÉMMIS has been working with community organizations and shelters, given that they are supposed to service the same community members.

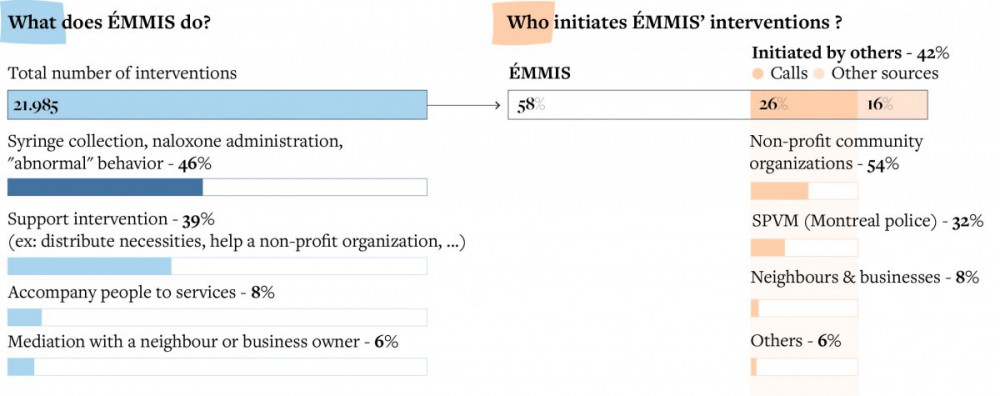

Visualization by Timour Scrève. Data from Guillaume Rivest on behalf of ÉMMIS.

“It’s an extremely demanding and extremely underpaid and undervalued type of work to do,” says Sparrow Preston, a social worker who has worked with front-line services in Montreal like youth shelters and a low-barrier wet shelter “that did a lot of harm-reduction focused work” for nearly a decade.

A crucial part of the job is building trust with the communities front-line workers serve, Preston explains. She says that it’s critical front-line workers across organizations be able to trust one another; regular communication between organizations is a necessary part of the job. If that trust is compromised, the support system that community organizations have worked so hard to create might break down, meaning more people fall through the cracks.

“Folks who use access services, who use a shelter, who maybe are someone that ÉMMIS would respond to, they build a relationship with those workers and when that worker is able to make what is called a ‘warm transfer’ to another service, because they know a worker there, that’s when programs like this are successful,” Preston explains.

46 per cent of ÉMMIS' interventions are for what the team as describes as "syringe collection, naxolone administration, and abnormal behaviour."

She calls ÉMMIS only when absolutely necessary. For example, if “we have someone who is really in distress and we need help transporting them,” she’ll call the service and ask, “Can you drive by and check on them? Can you see if you can help transport them somewhere else?”

Laura Aguiar, a project coordinator at the Iskweu Project, also avoids calling the service for similar reasons. “When there is a crisis, we have our established networks and people we call.” At the Iskweu Project, Aguiar supports families and friends of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, and trans and Two-Spirit people (MMIWGT2S). The project was started by the Native Women’s Shelter of Montreal as “a direct response to [the MMIWGT2S] crisis here in Montreal and throughout Quebec.”

Aguiar emphasizes that the trust of community members, and the relationships the Native Women’s Shelter of Montreal has built with the urban Indigenous women, girls, trans, and Two-Spirit people in Montreal, are essential to the Iskweu Project’s work. She wouldn’t refer a community member to someone she doesn’t know, “especially not for an Indigenous woman who is facing violence.”

58 per cent of ÉMMIS' interventions are initiated by the mobile unit.

Preston, Aguiar, and other front-line workers have developed an expansive network to support community members during their decades in operation, and to some it’s unclear whether the mobile unit truly works for the unhoused community and others in need of crisis support.

“10 years ago, the only people approaching unhoused people in a park or in a Metro and saying, ‘Hey, how you doing,’ and trying to build a relationship with them were street workers. And street workers work for the user, for the unhoused person,” says Ted Rutland, an associate professor of geography, planning, and environment at Concordia University whose research focuses on urban security and policing. “Now you’ve got these social workers approaching unhoused people the same way the street outreach workers do and trying to win their confidence, but they don’t represent the interests of unhoused people.”

In September 2023, Rutland published a report with the Réseau d’aide aux personnes seules et itinérantes de Montréal that investigated how effective ÉMMIS and the SPVM’s mixed units (units that consist of police officers and civilian psychosocial workers) are at supporting houseless people. As the researchers feared, their results showed that the teams served the interests of businesses and housed residents in the areas of operation rather than the people who need support.

Montreal has the highest number of police officers per capita of any major city in Canada, and public security is the largest line item in the city’s 2024 budget.

“What outreach workers said is that [...] the goal of ÉMMIS interventions is to remove someone from spaces where wealthier businesses and residents don’t want them,” Rutland says. “ÉMMIS functions to remove unhoused people from space [...] and represents the interests of people who do not want unhoused people there. It doesn’t address any of the reasons why someone may be there.”

Lelièvre also does not believe ÉMMIS operates as an alternative to the police. “Many of my police teams, such as the Équipe de concertation communautaire et de rapprochement, will work on the same areas in complement,” Lelièvre says. “There is no real difference, in that we will work on the same axis in terms of prevention and urban security, except that police can eventually be called to apply the law.” The team’s ability to answer non-urgent calls is proof to the SPVM commander that the mobile unit could be an effective ally in addressing calls for a solution to the increasing number of unhoused people in the city.

Looking to the future of ÉMMIS

Since his run-in with the police a couple of years ago, Peter has avoided accepting another ride from an SPVM officer at all costs, but he did accept one from ÉMMIS when he needed help moving his things again. For Peter, having the option to ride with ÉMMIS instead of the police was a relief: “I find it really good that they can help people, especially me with my foot” which was injured by the police, exacerbating his limp.

But Joey* is more skeptical of the mobile unit’s effectiveness. The policing alternative was created by politicians instead of front-line workers with experience with the houseless community, Joey explains. As a street worker with 30 years of experience in front-line services, he and his colleagues understand the requirements much better than the politicians who created and fund ÉMMIS.

Joey has worked at a number of shelters, including La Maison du Père and CACTUS Montréal, but he never thought he would end up accessing those services himself. After rents increased in 2020 at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Joey was kicked out of his apartment because he no longer met the landlord’s minimum income requirement to rent the unit.

Montreal’s shelter system has about 1,800 emergency beds, less than half the number of people without shelter.

“It makes me sad that after my 30 years in this field, in 2023, I have ended up on the street myself. It pisses me off, this economic cycle.” That economic cycle, according to Joey, is the one that reinforces class structures and continuously inflicts violence on marginalized communities. “I am done trying to understand this system.”

The Government of Quebec reported that over 4,500 people were visibly unhoused in Montreal in October 2022, 33 per cent more than in 2018. In recent years, the SPVM have responded to the eviction and houselessness crisis with increased violence, tearing down encampments despite residents having nowhere else to go. Montreal’s shelter system has about 1,800 emergency beds, less than half the number of people without shelter. When the city got its first snowfall of the season in November 2023, Montreal’s social services minister, Lionel Carmant, announced that the provincial government would finance an additional 188 beds.

Three weeks after the announcement, ÉMMIS made public that it would contribute eight agents to a joint effort with the SPVM and agents of Société de transport de Montréal to address the issue of people seeking shelter in metro stations and to make metro stations safer. Montreal has the highest number of police officers per capita of any major city in Canada according to data from Statistics Canada in 2022, and public security is the largest line item in the city’s 2024 budget.

“ÉMMIS functions to remove unhoused people from space [...] and represents the interests of people who do not want unhoused people there. It doesn’t address any of the reasons why someone may be there.”

Rutland says ÉMMIS’ expansion won’t resolve the crux of the issue: unaffordable housing. He would like to see an end to “funding organized violence” and for ÉMMIS’ and the SPVM’s $10 million and $821 million respective yearly budgets to fund more social housing and a transportation system for unhoused people controlled by community organizations. Joey would also like to see some of ÉMMIS’ budget redirected to building social housing so that people with lower incomes like himself can afford shelter.

With $50 million invested in the program over the next five years, ÉMMIS is rapidly expanding. The mobile unit had offered a ride-along to Briarpatch in mid-October 2023 to report on the story, but after rescheduling once, ÉMMIS rescinded the offer due to the program’s growth.

ÉMMIS workers are enthusiastic about the expansion and their work in the community. “We are really in an optic of trying to help people,” Noure says. “But we also keep in mind that we need to make people aware of their responsibility. Us, of course, we are always working toward finding the best solution possible, but we equally want the person to participate in their journey toward finding a solution.”

*Joey and Peter’s names have been replaced with pseudonyms to protect their privacy. ÉMMIS workers requested to be referred to by their first names because of the nature of work and for privacy reasons. Alexandre Lelièvre, Noure, and Frédérique’s quotes have been translated from French by the author.