In 1969, Canada tried to abolish its treaties with First Nations – to dissolve their reserves and forcibly assimilate them. The effort catalyzed uprisings coast to coast, forcing the state to withdraw its infamous White Paper (the document outlining the dissolution plan) the following year. But Indigenous resistance continued unabated. Amid the rising Red Power movement, state officials were concerned by Indigenous peoples’ increasing defiance of Canadian law and order and their hostility toward the settler police officers who enforced it.

Canada came up with a savvy fix for this crisis of legitimacy and to neutralize the burgeoning threat: Indigenous cops. In Quebec, for example, the state helped set up and fund the Amerindian Police, a semi-autonomous force staffed entirely by Indigenous officers, which served about 25 reserves across the province.

The optics were good, and evidence suggested Indigenous people may have felt less hostile toward police who shared their background. Police also became more accessible. Prior to the changeover, law enforcement seldom came onto reserves. Response times had been measured in hours, but a number of small reserves now had their own local cops on the beat.

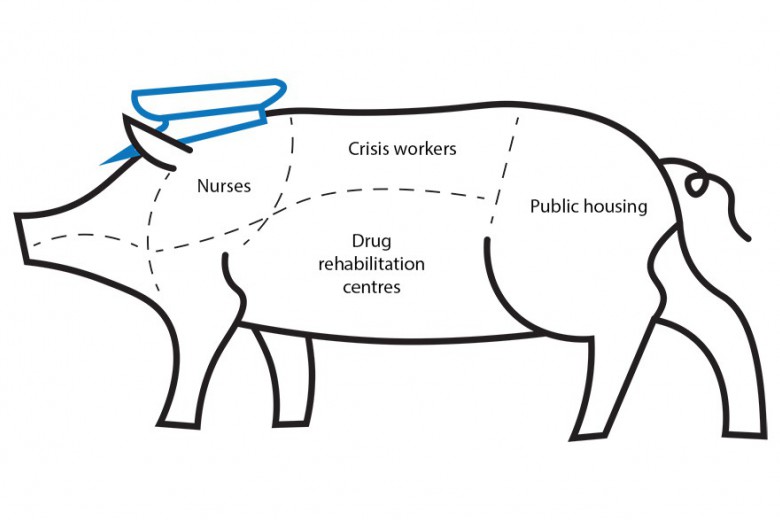

But the Amerindian Police often doubled as the only public service. Many reserves barely had infrastructure for electricity or plumbing or telephones, let alone other necessities settler communities already took for granted. Amerindian Police officers were “part social worker, taxi-driver, alcohol worker, ambulance driver, peace-keeper and dog catcher.” People turned to the police for all kinds of help because there was no one else to call, which turned everyday situations into potential crime scenes. Arrests rose on reserves with the Amerindian Police.

–

Nearly 50 years later, almost nothing has changed. Canada has expanded policing – Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike – while shirking responsibility for other public services. There are more cops per capita in Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, and the Yukon as in the rest of the country, which fuels over-policing and mass incarceration. People in Indigenous communities are more likely to be arrested for minor crimes like mischief and common assault, which often go unpunished elsewhere.

Given the availability of police officers amid shortages of care workers, a recent paper by two researchers offered a solution to reform Indigenous policing: cops could use their body cameras to livestream their interactions with people to mental health professionals, a practice already in place in some settler forces. The idea is that the mental health professionals can offer police advice on how to act like social workers while handling mental health calls. The proposal fits a long-standing pattern: policing is the lens through which the state sees Indigenous people. Back in 1983, a study found that the state spends disproportionately on “coercive social control” – like policing – in Indigenous communities, whereas settler communities enjoy a greater emphasis on “consensual social control,” like good schools and reliable energy grids and tap water that’s safe to drink.

To be clear, the policing on reserves is substandard. Indigenous police services are underfunded compared to their settler counterparts. Their officers earn less and they have worse equipment, like expired bulletproof vests. If Indigenous communities have the right to the same standard of policing as everyone else, then the state should pour money into policing for reserves.

But the state underfunds everything in Indigenous communities, including schools, health care, housing, and infrastructure. Indigenous leaders have called for more resources for all of those things, as well as for Indigenous policing, but history suggests that they may only get more policing. In the U.S., Black communities in the 1970s pushed for more law enforcement to get tough on crime, as well as for job programs and other basic services. All they got was the law enforcement, setting the stage for skyrocketing incarceration rates. Allocating more money for Indigenous policing – instead of first funding fixes to root causes of violence, like overcrowded homes and poverty – will likewise only intensify the criminalization of Indigenous communities.

Worse, it risks further eroding the sovereignty of Indigenous peoples.

Back in the 1970s, Indigenous policing might have seemed like progress, the same way many once believed that Black police officers would transform law enforcement (instead of just acting like their pre-existing co-workers). Indigenous peoples would have the opportunity to police their own communities, a privilege previously reserved for white interlopers. Some thought that Indigenous cops would behave differently than settler cops. Some were also led to believe that forces like the Amerindian Police would be part of a transition toward local control over the administration of justice.

Canada’s legal system, founded on punishment and deterrence, is incompatible with the traditional practices of many Indigenous peoples, who largely maintained order through reparations. Some believed Indigenous policing was a step on the road toward re-establishing those traditions.

But Indigenous policing has proven hard to distinguish from regular settler policing. Indigenous police forces are trained at a Canadian police college to enforce Canadian laws. They have good relations with settler forces, frequently collaborating on police work and hiring each other’s personnel. Indigenous police forces have even expressed interest in helping the state manage Indigenous protests, offering intel on local Indigenous activists. The vague promise that Indigenous policing would be “culturally appropriate” has ultimately meant only that the police officers arresting Indigenous people are Indigenous, too.

Indigenous police forces are seizing the mantle of so-called justice, meting out settler-style law and order under the guise of Indigenous control. For example, Nipissing First Nation has tried to rework their justice system – to move away from Canada’s carceral practices and toward peacekeeping and restorative systems. Anishinabek Police Services (APS) – their local police agency – has stood in their way, according to Miskaankwad Dwayne Nashkawa, an official with Nipissing First Nation. The police have refused to follow anything other than provincial and federal law. Nashkawa writes that for APS Deputy Chief Dave Whitlow, “First Nation laws aren’t real laws unless they are blessed by the Crown.”

“The police services working in our nations are probably more disconnected from our aspirations to become self-governing than [they have] ever been,” Nashkawa writes. The APS has “come to reproduce the very same challenges we sought to get away from in the first place. As we collectively move towards asserting jurisdiction, First Nations require a new conversation on how we’ll enforce our laws, in our own ways.”

_780_520_90_s_c1_c_b.jpg)