Editor of The Independent, Justin Brake reported on the Indigenous-led mobilization in opposition to the construction of a hydroelectric dam at Muskrat Falls, Labrador, in the fall of 2016. He was named on an injunction* during the occupation and charged in relation to his coverage of the events. On the other side of the country, Kanahus Manuel has spent years fighting the corporate encroachment of mining and energy companies on Secwepemc territories in B.C.

Briarpatch invited Brake and Manuel into conversation to discuss what lies ahead in the struggle to protect Indigenous land and the legal freedom to document the ongoing struggles against dispossession. The conversation was transcribed and edited for length.

Justin Brake: I live in Ktaqamkuk, Mi’kma’ki – what’s known to settlers as Newfoundland. I didn’t come to learn about my Indigenous ancestry until only about 10 years ago, so I’ve been spending a lot of time and energy trying to explore what that means and if it changes anything for me in my life.

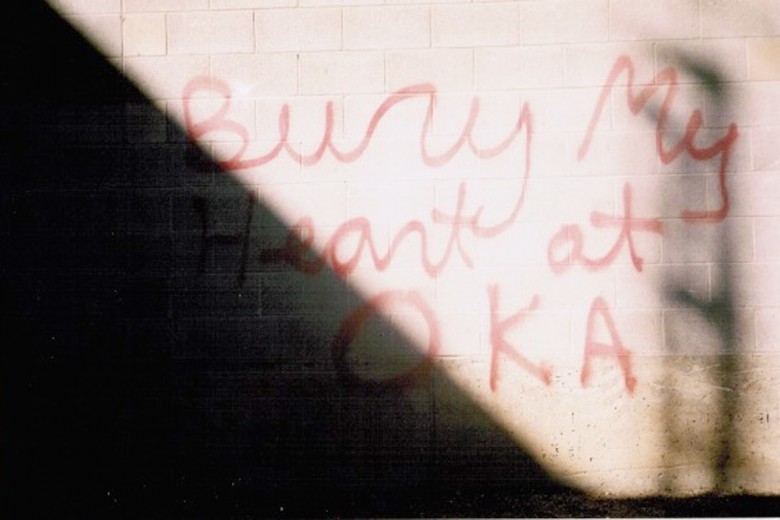

I covered the resistance to Muskrat Falls. The protests escalated to a blockade and an occupation of the site, which forced the premier of Newfoundland and Labrador to meet with the leaders of Labrador’s three Indigenous groups and agree to some demands set out by three Inuit hunger strikers who were part of the protest. It was a victory for some, but many people are not happy because the dam is going ahead anyway and they’re afraid it is going to cause a lot of damage to their way of life, their water, and their food. There are upward of 60 land protectors who are facing criminal and civil charges because of those protests. I was also named on a court injunction because I was on the site covering the occupation as a journalist.

Kanahus Manuel: I’m Secwepemc and Ktunaxa, and our territories are in so-called B.C., though the Ktunaxa territory extends south of the medicine line to the so-called U.S. I was born to a very political family. My grandfather is Grand Chief George Manuel and my father, who passed on in January, is Arthur Manuel. It was agreed within our family that I would continue to speak out on the B.C. treaty process, the Trans Mountain Kinder Morgan pipeline, and the Imperial Metals mine – they’re all linked.

I have also been named in injunctions, including in our fight against the Sun Peaks ski resort and the Imperial Metals Mount Polley mine disaster in 2014. I did around 80 days in jail for defending our territory. It’s interesting to hear about Muskrat Falls. We need to be more aware of the big battles happening in the country and be able to show our solidarity on the West Coast here and all across Canada for these issues.

Brake: A lot of these resistances are in very remote areas, particularly in the North. Often, there isn’t a media presence, so people don’t see with their own eyes or hear with their own ears what is happening. That seems to be changing with social media. It gives me some hope that journalists, non-journalists, or citizen journalists can be documenting these resistances and making sure that voices that are often marginalized by mainstream media can be heard. The terms land defender and water defender are starting to come into the mainstream because there is a growing amount of media coverage; maybe that’s attributed to social media more so than to traditional media. What does it mean to you to be a land defender?

Manuel: We come from an area with so much water. We have cactus that our people would eat, mountain huckleberries, blackcaps, animals, salmon. All of this is so important for us as Secwepemc people to continue on as who we are. If anything threatens this, we as Native people really feel it. One of the sisters in the east, Amanda Lickers, dubbed the mental, spiritual, and physical trauma of our land being destroyed and contaminated [as] “land trauma.” As my grandfather, George Manuel, always said, our culture and our language flow from the land.

Elders at our band meetings said, “We have to do something,” slamming their fists on the table. “Where are our warriors?” They were looking right at me.

When the $70-million Sun Peaks ski resort expansion was proposed in our territory, Elders at our band meetings said, “We have to do something,” slamming their fists on the table. “Where are our warriors?” They were looking right at me. That’s the moment in my life when I said, “What am I doing to stop these machines from destroying the land?”

We’ve seen court decisions in favour of Native people, including the Delgamuukw decision in 1997. Everyone thought that the government was going to put our land on a platter and give it back to us. My dad said, “No, we are going to have to assert our title and our rights to our land. That means occupying our land. That means continuing to hunt and fish off our land.” Now here we are, sitting on our little reserves, while, nationally, 62 per cent of our people are living off reserve. One hundred and fifty years – that’s Canada’s colonization bomb, and our people are just dusting off the rubble now. It’s the first generation out of residential schools. Now [people are] here saying, “I am a water protector” or “I am a land protector” because they so much want that connection to the land again.

Brake: When the resistance began at Muskrat Falls, there wasn’t a strong identity of land protectors. But at one point, people walked onto the dam site. They held prayers and water ceremonies and prayed for the water and for strength to stop what they called the destruction of the land. One day, they read a statement and called themselves land protectors and said they didn’t recognize the corporation’s right to the land as granted by the government. What can you say about the process of how Indigenous lands are privatized, often in a way that poses risks to Indigenous people?

Manuel: My grandfather, Wolverine, would say, “The province of B.C. has no jurisdiction. There’s no treaty and no purchase. Therefore, the province has no jurisdiction over these lands.” All across Canada, the government is pushing modern-day treaties. They may call it a comprehensive claims policy or the B.C. treaty process, but a lot of these new agreements force Indian bands to sign away our rights to the land.

People try everything to fight against these corporations. Canada got rich on the minerals, timber, and fisheries, and now they’re using that money to oppress us with their military, police, and judicial systems.

Brake: I spoke with Pam Palmater about the Muskrat Falls case, and she likened land defenders to Native warriors in traditional societies. She said that the warrior spirit that people on the front lines have is a rare quality. People who are not on the front lines, who can’t or don’t want to be on the front lines, but want to participate, can wrap their arms around land defenders and support them.

There are only about 26,000 people in Labrador, spread out over quite a vast geographical area, so protests have never been huge there. Some Elders say these are among the largest protests in recent years, and the only ones where Inuit, Innu, and settlers came together in resistance. And though they gained quite a bit of popular support, the land defenders are still facing charges, and they’re relatively alone in that sense. There has been no major rallying effort among the public to support them, financially or otherwise. You’ve pointed out there are six occupations and resistance camps across Turtle Island, but I’ve only really heard of Unist’ot’en and maybe one other one. How does this fragmentation in awareness get addressed? Do you see a beginning of unity among various groups in so-called Canada?

Manuel: Defenders of the Land recently had a big gathering in so-called Vancouver that focused on the Unist’ot’en camp. Now, non-Native supporters are organizing themselves as Indigenous solidarity supporters, as builders who build homes on the territory, media and communications teams, a transportation team.

One of the inspirational moments here in B.C. involved the Native Youth Movement. They held decolonization workshops with young people in Indigenous communities. They asked, what does it mean to pull ourselves out of this system? What does it mean to have self-determination, to eat traditional foods, to start organizing language immersion camps where we just speak our language and are not forced to speak in this white man’s tongue? We can’t say, “I’m fighting against this corporation” but still want to live the white man’s lifestyle. It can’t go hand in hand. Some people say we have to walk in both worlds. No, we’re trying to transition out of the white man’s world because it’s going to destroy the planet.

Brake: When you’re talking about the leadership of Indigenous people in addressing climate change and the continued destruction of Indigenous lands by capitalism, you see land protectors facing injunctions and facing charges. How do you navigate that? I’m a journalist facing charges, and the energy I have to put into defending myself against these charges means I have less energy for the journalism I want to produce. What does that mean for a land defender?

Manuel: When I was down south with direct-action Moccasins on the Ground training, I met an amazing storyteller. At the time, lightning was coming down all around us. This man said, “This is the tactic that Crazy Horse used when he was fighting the invasion. We’re like the lightning strikes and we’re coming at them from every angle. That’s the way we need to fight.”

We need to be coming in from every angle because it’s going to take a lot to come up with the strategies that will work in our favour.

If everybody could get organized in their communities, we’d see a lot of people fighting. At the peak of Standing Rock, there were thousands of people at the camp. To be organized with thousands of minds and skill sets is a very powerful force. It’s going to take us as Indigenous grassroots people to get ourselves organized.

Defenders of the Land and Idle No More woke up our nations to say, “We have this many people that are on our side for the Earth, for the land.” Now it’s up to us as organizers and as leaders in our communities to really pull all those numbers together. As you said with Muskrat Falls, our communities face mass arrests and criminalization. Mothers and youth face jail time for standing up for our lands.

But hearing this story of solidarity could lift someone’s spirit up so that they can continue this battle. It’s amazing how many people have hope that, one day, we will have freedom on our territory. We feel it when we’re on the top of the mountain picking huckleberries with no one else around except for the bears.

Brake: In a 1993 submission to the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, the Canadian Association of Journalists said that “the country’s large newspapers, TV and radio news shows often contain misinformation, sweeping generalizations, and galling stereotypes about Natives and Native affairs.” Most Canadians have little knowledge of Native peoples or the issues that affect them. But when [Indigenous] people protest or make noise in defense of their land and rights, there is more coverage of Indigenous people.

According to a Journalists for Human Rights study of media coverage of Indigenous issues in Ontario between 2010 and 2013, as coverage related to Indigenous protests became more frequent, the proportion of stories with a negative tone correspondingly increased. I only read this after I covered the Muskrat Falls protests, but I’m concerned about the state of journalism with respect to how journalists, particularly non-Indigenous journalists, cover Indigenous struggles.

If I am convicted, it could set a precedent in which no journalists could follow major stories of Indigenous struggles, or any other marginalized group fighting for their rights, on “private property.” Press freedom doesn’t exist if journalists can’t follow stories like occupations and blockades. Do you have hope that the journalists bringing light to Indigenous struggles can successfully fight Canada’s legal system and protect the right to do good journalism? Or are we already too far gone in the state of Canadian journalism? Is it up to Indigenous people to learn how to become citizen journalists and document their own struggles?

If I am convicted, it could set a precedent in which no journalists could follow major stories of Indigenous struggles, or any other marginalized group fighting for their rights, on “private property.”

Manuel: One thing that we can be clear about is that nation-states are very fearful of us when we can get the truth out. Mainstream media often sides with corporate interests and the government, and a lot of time it’s a racist perspective because they don’t understand our land issues. When we do have our own journalists, it gives the power back to the people.

I want to encourage young people to pick up their phones and start documenting. We’re lacking journalism coming out of isolated communities. This is an opportunity for young journalists to get our true message out.

It’s really important for our people to stand behind those facing criminal charges, whether they’re land defenders, water protectors, Native people, or journalists. People often don’t feel like they’re supported when they’re in the courtrooms. I was thrown in jail and denied bail, even though my baby was still nursing. That’s scary because once they have you in their clutches, you can’t fight.

Brake: APTN has been tremendously supportive of me. They’ve offered to seek intervener status in my case to make an argument about how devastating it would be for journalists covering Indigenous protests if I were convicted. Privately, some journalists have been supportive, but there has been relative silence among the Canadian mainstream media.

I hope that once I’m through all the legal headaches, I’ll be able to develop or participate in training with Indigenous youth across Canada and across all nations. Maybe this is the beginning of something.

Manuel: When we’re on the front lines, we are documenting Indigenous rights and human rights violations, and we need to document it in a way that these could be internationally submitted with human rights complaints or be court admissible. Grassroots people who are picking up cameras to ensure there is documentation are also human rights observers.

Editor’s note: In the print version of this interview, the introduction states that Brake was arrested for his coverage at Muskrat Falls. He was in fact named on an injunction and threatened with arrest, but was not arrested. We apologize for this error.