In a small building in Montreal’s east end, Maxime Aurélien sits behind the counter at the back of his pawnshop and barbershop Cash Content. He notices me in the doorway, smiles, and welcomes me in. It’s a late afternoon in November and the store is lively and cozy: drawings and texts decorate the walls, and the smell of incense fills the space. To the right of the entrance sits a barber’s chair, and to the left, clothes and other items are up for sale.

A Haitian refugee who fled the Duvalier dictatorship in the 1970s, Maxime tells me he has always done what he needed to do to get by. In 1995, he opened Cash Content to support his family. But before becoming a business owner, he led a very different life; he was formerly the leader of the street gang Les Bélangers, Montreal’s first Haitian street gang.

I join him at the back of his store where he tells me about his path, the systemic racism and police violence he endured, the inspiration that led him to write Out To Defend Ourselves with Ted Rutland, and from what, exactly, he had to defend himself.

I really wanted a gang – not a criminal gang, but a gang so we could defend ourselves against white people who beat us up.

Beck Why did you decide to write Out To Defend Ourselves?

Maxime People don’t know our reality. [Les Bélangers were all Haitian, and] we came [to Canada] at a young age. I was 10 when I arrived [in Montreal]. There was a lot of racism back then. Everywhere we went, we were called “dirty n****r” and told to go back to our country.

The older [Haitians] wouldn’t say anything because they’d just come out of the dictatorship. They didn’t want to have to deal with the police. They’d already had bad experiences and weren’t looking for trouble.

It’s not that we wanted to be in trouble, but we were young. We wanted to explore the city. But every time a white person spotted a group of Black kids, they felt the need to call the police. So, we kept getting arrested.

We were just walking around yet were seen as thieves, thugs! But we were just a gang of friends! We went to the same school, played sports, and defended ourselves against any white people attacking us.

Beck Were there any neighbourhoods off-limit for Les Bélangers?

Maxime Westmount! [laughs]

[For context, Westmount is one of Montreal’s wealthiest neighbourhoods. It’s also overwhelmingly white, with 79.6 per cent of residents identifying as white and only 1.8 per cent as Black in the 2021 census.]

Beck Did you experience a lot of racism at school, too?

Maxime No, because my father watched everything that was going on there. In our area [the east end of Montreal], every time a group of Black children was spotted, the police were called, and the kids were sent home. The Black kids were being deprived of days at school. My father noticed and decided to send me to a private school, which saved my life. [But] I missed my friends.

Beck You also lived in New York. What differences in racial tensions did you notice between New York and Montreal?

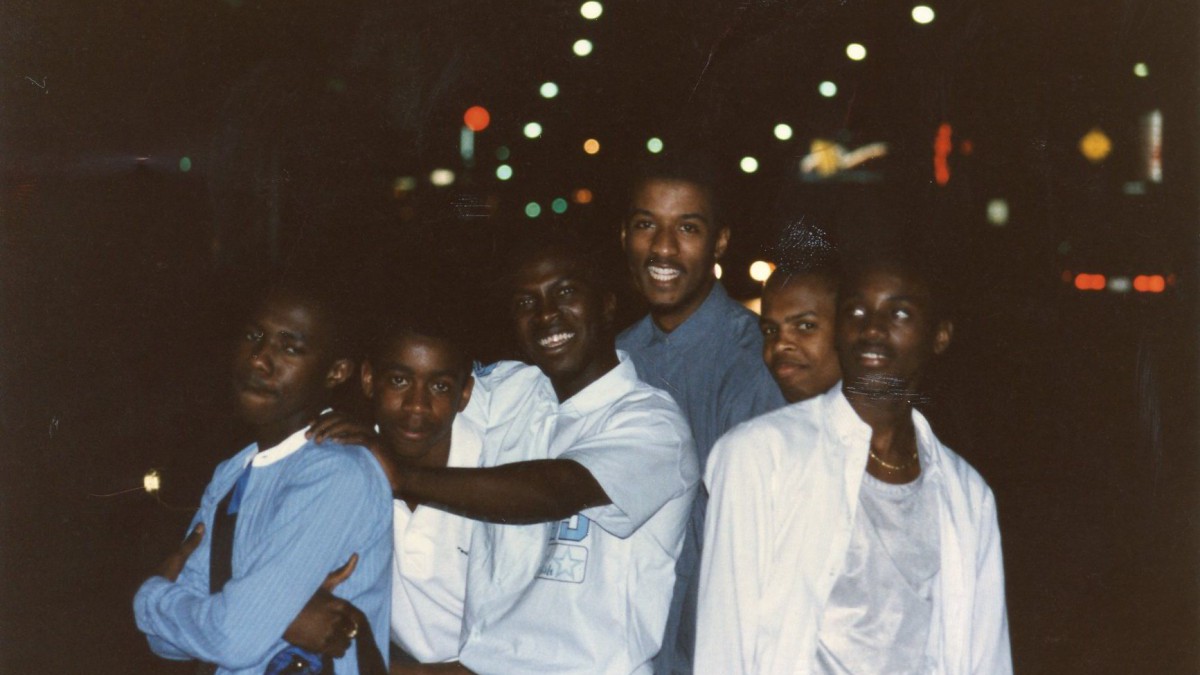

Maxime (left) and friends pose for a photo in East Flatbush, Brooklyn.

Maxime [My family] didn’t stay there long, about a year and a half or two years, but we went back every summer after that. I saw the difference between American culture and the culture here. In the predominantly Black neighbourhoods of New York, there wasn’t too much racism. White people just didn’t live there. It was segregated that way for so long, and it seemed that white people didn’t interfere.

It was a little different in the countryside because [white people] weren’t used to seeing Black people. Our appearance would mostly intrigue them.

But here, they hated us. Every Friday, [my friends and I would] go to Berri-UQAM [metro station] and fight. We knew there would be white people who didn’t want us there. It almost became a game, and a game we enjoyed playing.

Beck It was like a game to you?

Maxime Yes, we loved it. It was confrontational. We knew they were going to chase us, and, as soon as they did, we knew where to go because we knew the streets. It was fun!

We used to take the bus around town to learn the street names by heart, without our parents knowing. We’d get to know the city. But no matter where we ended up, the police would be called without fail.

We were just walking around yet were seen as thieves, thugs! But we were just a gang of friends!

I was considered the leader of the gang because everyone gathered at my place. But after a while, it wasn’t as much fun, especially for me. My mother had passed away. The parents of the other kids didn’t want their kids to see me anymore and thought I was a bad influence on their children.

Beck Did Les Bélangers come together organically because you were already being targeted, or was it more intentional?

Maxime I really wanted a gang – not a criminal gang, but a gang so we could defend ourselves against white people who beat us up.

On TV, I’d see criminal gangs. [They] presented themselves as if it was normal [to be in a gang]. In my head, it was illogical: how could anyone freely advertise themselves as a criminal? [But it also] made me want to do it. [I said to myself,] “you’ve got no money, you’re in total poverty, fuck!” [and] thought, as a Black man, why can’t I do it?

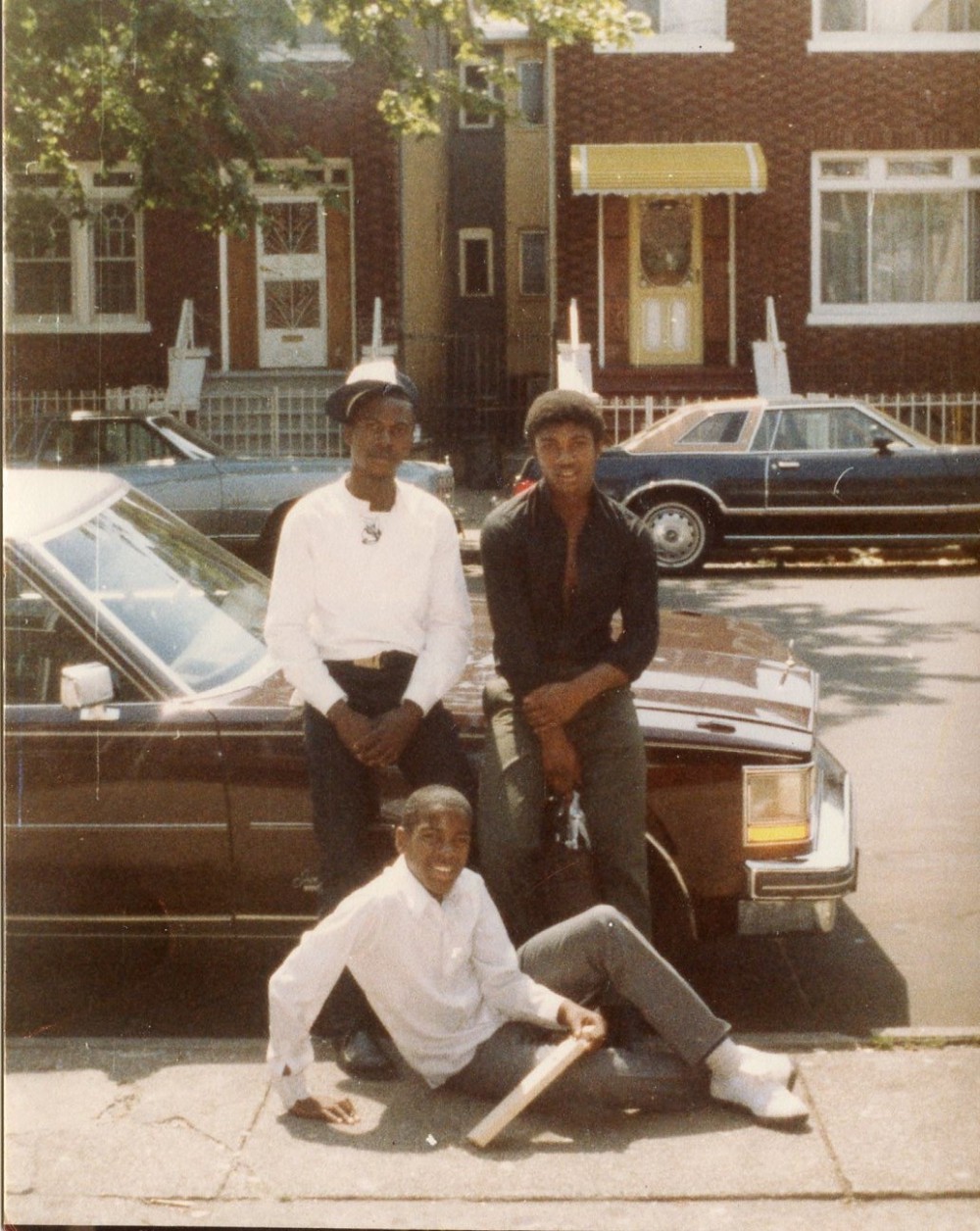

Maxime (left) and Les Bélanger member Ducarme stepping into a borrowed car in Montréal-Nord.

Beck To pay the rent.

Maxime To pay the rent! In the beginning, that was my goal. My mother had died, and when I was 18, my father sent me to the United States, but I didn’t stay there for long. I lived with my aunts, and there were six of us in one room. It was too much. I had one more year of high school to do in the U.S. but I didn’t feel like it. I came back to Montreal and took a CEGEP course. I was 18 and on my own for the very first time in my life.

But I didn’t think of myself as an adult. All my life, I had been told: ‘you’re not a grown-up.’ But now, all of a sudden, I had responsibilities: paying rent, going to school – but I had no money. I went to class hungry. My teacher suggested that I model, and I did. I made some money and was able to buy materials for my classes. But it didn’t last.

We acted the way we did back then because we had to survive.

I was hungry. The rent wasn’t too bad, $250 a month. I was on welfare because I had not been granted loans or bursaries [by the Quebec government]. I was getting $150 a month, which wasn’t enough to pay rent. That’s how you start doing bad things.

Beck What kind of trouble would you get into?

Maxime One day, a friend took me to a place to steal. I mostly took what I needed: napkins, utensils, food, toilet paper, towels. I was always called a fool because I didn’t steal things that were more valuable. Then my friend stopped, but I continued. I’d been taught something that allowed me to survive, so I had to keep going. There was also a lot of racism. It’s not that I didn’t want to work, they just didn’t want to hire us. On the phone, you’re a Quebecer. But when you get there, they realize that you’re Black and don’t want to hire you.

Beck That must have been very disheartening.

Maxime I told myself I’d figure it out. I kept on stealing; I knew that if I didn’t, I’d be on the streets. You’ve got to eat, you’ve got to pay rent. It was hard.

I moved every three months because I couldn’t make ends meet. I moved by bus. I’d put all my stuff in a bag and take my mattress. The bus driver would wait for me, and I’d get on the bus with everything. Successful people went to school or had parents, but bums like us didn’t stand a chance. It’s not the same when you have no money.

The word “gang” has a criminal connotation, and it’s mostly used in reference to Black people.

When you don’t have money, they throw you in jail. At a certain point, I was frustrated with the fucking system. I was sick of not working, I was sick of being called a dirty n****r. On top of that, I saw how organized crime brought people money.

[Maxime, who had been laughing throughout the interview, began to shed a few tears, mixed with bitter laughter].

Beck How was your time in prison?

Maxime Prison was therapy for me. In my mind, what I had done wasn’t a crime; I hadn’t killed or raped anyone. Yes, I know that stealing is a crime, but I had to survive.

[Lawyers told me] to avoid prison if you didn’t have any money, you had to plead guilty. We were told that if we pleaded guilty, we could leave. And since we didn’t want anyone to know we were going to prison, we agreed to plead guilty. But, in doing so, you stayed in the system, but I didn’t care. And depending on where you were sent, it was possible to be comfortable there. I was transferred to Bordeaux. It had an open area where we could play basketball. I could eat. It was so much better than being outside. I had a break from my shitty life. But reality does eventually catch up with you. You leave prison with a criminal record, which makes it impossible to find a job. You’re permanently marked.

Beck How did Les Bélangers dissolve?

Maxime The police had identified me as the leader, because as I mentioned earlier, everyone was meeting at my place. The police were constantly hovering around my place. It became impossible to meet there because I kept getting arrested. At the same time, we got older and saw less and less of each other. But the police interventions definitely accelerated the process.

It’s important for the world to know who we were. We weren’t criminals – we were just a gang of friends.

Beck How did you go about starting your business?

Maxime Out of frustration! When we worked for white people, we were constantly insulted. You either had to fight or make yourself small. We were told that we were too stupid, too smart, stealing their jobs. That’s what forced me to do things for myself. I wanted to work.

Beck Why was it important to write about your experience in the book Out To Defend Ourselves? Were you happy when Ted Rutland suggested the idea, or did you have reservations?

Maxime I was really happy about it! I think it’s important for the world to know who we were. We weren’t criminals – we were just a gang of friends. But the label ‘criminal’ has followed me all my life. Once you do time, you’re considered a criminal.

Writing the book was mostly Ted’s idea. I lived through what I lived through, but I never thought of writing about it. Who was I to do so?

Beck What would you like people to take away from your story?

Maxime The same people who used to hit us now have children who go to school with us. We used to be apart, but not anymore. It’s easier for young people to get involved in crime than it was before. Some young people don’t understand why we take the bus while others have a car. [But now], young people see all that money can offer. The more money you have, the higher the chance of not falling [into crime].

When you’re Black, and no one respects you, money may seem like the only way to get respect.

Beck What would you like people to know about Black street gangs?

Maxime The word “gang” has a criminal connotation, and it’s mostly used in reference to Black people. In the early days, Les Bélangers was just a gang of friends, nothing more.

Beck What does self-defence for Black men look like today?

Maxime I think that self-defence has to do with empowerment. We acted the way we did back then because we had to survive. Now it’s maybe less about survival and more about respect. When you’re Black, and no one respects you, money may seem like the only way to get [respect].

*This conversation has been edited for length and clarity. It has been translated from French by Christelle Saint-Julien.