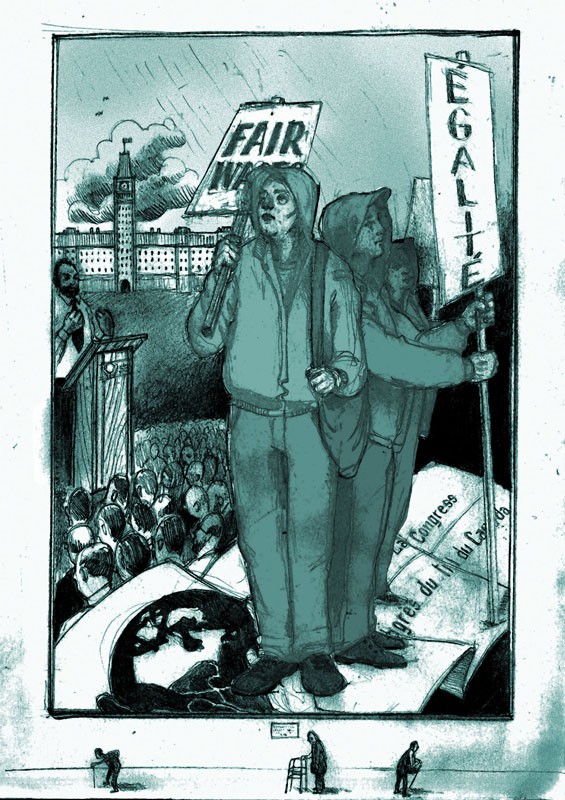

The status quo is not working for working people. Unions need to seriously overhaul the way they operate if they are to remain relevant. One key example that reveals the directionlessness and impotence of contemporary unions is the perennial convention charade where the organized labour movement convenes with the professed aims of advancing the interests of workers and improving society as a whole. If only this were the case.

With few exceptions, a recurring drama plays out at conventions on the backs of working people, “full of sound and fury; signifying nothing” (to quote Macbeth.) Here are some of those recurring acts that paralyze a movement.

Every convention begins with some kind of rhetoric about “democracy” and the importance of the labour movement coming together to debate and participate with a view to social progress. Seriously, who are we kidding with this pretend democracy? Labour conventions are typically contrived. Everyone knows the fix is in – but no one wants to say it out loud. In some cases the problem goes as far as paid staffers attempting to influence the proceedings in the backrooms or even acting as delegates, when for all intents and purposes they are actually representing their employers, the top elected officers.

Limited debate

During these precarious times, one would think this coming together every three years would lead to deep and fiery discussions on where our labour movement is headed and what it will take to develop an effective resistance. Just the opposite is true. For example, during the 2011 Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) convention, debate was limited to approximately nine hours for an entire week. This script ensures that workers, representing their unions as delegates, will have precious little time to debate the issues. Further, the show is always conducted by those orchestrating the front stage at the expense of the delegates who become mere spectators of the labour scene.

Speaking out in the context of a union convention feels much like speaking out of turn in church. You know how far you can go and where to stop. Some topics, like any critical reflection on the relationship to the New Democratic Party (NDP), capitalism, class, strategy, and especially direct action, are mostly off limits and treated as unmentionable.

Time is typically stuffed with uninspiring speakers – very few could be described as especially challenging or insightful. Given that some unions hold seminars for the purpose of educating members, this is highly disappointing. Another problem is that some speakers from the floor have more rights than others, which is reflected in the amount of time allocated to delegates to speak.

The CLC achieved a new low at the last convention when space was taken up by CBC personalities Ian Hanomansing and Wendy Mesley. Hanomansing, serving as a moderator, voiced his disapproval with the claim that a corporate bias exists in mainstream reporting. The problem, according to Hanomansing, is that the left fails at both making their stories sexy enough and packaging their message as well as the right, thus confirming that journalism in today’s mainstream media is more of a public relations exercise than about finding and reporting the news. I guess Hanomansing means that journalists shouldn’t be doing the work of putting stories together and that in essence everyone is on the same playing field with equal resources to have our stories told. Migrant farm workers, for example, then must be assumed to be in the same position to tell their story as Jason Kenney, the Minister of Citizenship, Immigration and Multiculturalism. To further demonstrate the disingenuous nature of union convention debates, questions for panellists had to be submitted in writing, thus ensuring no challenging or embarrassing moments for invited guests. A debate that is scripted is in fact not a debate at all.

Rhetoric no substitute for action

Labour conventions are long on rhetoric but short on substance. The process is predictable and repetitious. Speaking to the converted, the right is assailed and the NDP lionized. Meanwhile, labour leaders – except during the occasional election – prop each other up, slap one another on the back and avoid discussing the systemic problems plaguing workers or naming the elephants in the room all the while preferring instead to heap on personal accolades. Personality politics, not discussions of political systems, fill the space and agendas. So-and-so is a “great guy,” a fighter for their members, a hero in the fight against Prime Minister Harper, or whichever non-NDP leader is in office. Delegates cheer. Little happens. But in those moments, under the lights in the house of labour, we sure do feel good about ourselves. There is a fetish about leadership and playing follow-the-leader, but nothing comparably passionate about the significance of struggle and the necessity of resistance. It’s easier for the union aristocracy that way. No one need feel uncomfortable.

I wonder if anyone was listening when the Manitoba Federation of Labour (MFL) convention guest speaker, Canadian Union of Postal Workers President Denis Lemelin, broke the mould somewhat by calling on labour to develop our own “social project”? Lemelin explains that sectoral divisions and defensiveness can be replaced by a basis of unity with a clear long-term strategic plan to gain public support and fight for all of society.

Silencing dissidents

It is noteworthy to see who gets in and who doesn’t at labour conventions. At the Montreal 2005 CLC Convention anti-poverty activists from the Belleville Tenant Action Group, fundraising in the main lobby of the convention center, were threatened with expulsion until delegates passing by came to their defence using a little direct action of their own.

While labour conventions are a place to pick up information, finding a table of radical or challenging literature may be difficult. There is limited space, and the organizers have final say over who is invited and who isn’t. A number of spaces were taken up by insurance companies at the recent MFL convention held in June 2012. Regrettably, challenging or critical materials were in much shorter supply.

Backroom mechanisms, never out in the open, are used to keep resolutions that may not be palatable to the leaders from ever making it to the floor. It matters not where the resolution came from (a local union, workers from the shop floor). If it seems “controversial” or doesn’t fit the pre-structured schemes of leadership it may magically disappear in spite of “process.” A case in point is the recent MFL resolution on Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) directed at Israeli Apartheid. While the resolutions committee recommended concurrence unanimously, behind the scenes the MFL executive asked the committee to reconsider its decision. Concurrence was pulled under the guise that the resolution did not reflect CLC policy. This raises the question of who gets to decide policy for organized workers in Manitoba. It does not appear to be a bottom-up process, but instead, a top-down corporate model. After some wrangling, face-saving, and negotiation, the resolution received again the desired concurrence only to have the motion tabled on the floor after a number of delegates spoke in its favour. To add further insult, activists were prevented from distributing information on BDS and the situation of Palestinians to delegates, even though that literature was produced in a unionized print shop.

Manitoba requires 65 per cent sign-up to certify a union. Two bold activists held a silent protest during Premier Greg Selinger’s speech to convention delegates by holding up signs pointing out that a government majority can be achieved with much less than 50 per cent of the votes but for workers in Manitoba, the bar is set at 65 per cent, the highest in the country. They were told to sit down. Silence and politeness remain the order of the day, thus making any criticism of the NDP off limits. The Manitoba NDP have been in power for 13 years and did not deliver on anti-scab legislation (now called “replacement workers” by organized labour, an example of neoliberal Newspeak that incorporates the language of the right). While perhaps an NDP government is not quite as hostile as a Tory one, can a “lesser of the evils” really be considered enough of a victory? Neither the NDP nor organized labour challenge the neoliberal capitalist system; in fact, neither can even bring themselves to utter the words to address its very existence.

Toothless resolutions

Resolutions have become a kind of shopping list without any pith or substance. Mostly toothless, they allow us to feel good about ourselves, as if we crossed another one off the list of things that need doing without the slightest mention of how we are going to do them. At the MFL convention 172 non-administrative resolutions were submitted. Of these the resolved action called on lobbying the provincial government 110 times. Sometimes the resolution stated the MFL will “continue to lobby” on an issue indicating that this is not the first time the issue was raised. The word “urge” is used 12 times, “encourage” five times, and “call on” three times. Stronger words like “demand” and “insist” were used four and two times respectively. This begs the question, what do we mean by lobby, urge, and encourage exactly? Does it mean beg, plead, take a minister to dinner, or mobilize a movement that can ensure the stated goals are met? Why do union conventions spend so much time, effort, and expense to make empty pleas and to obediently prop up governments and their agendas that clearly work against workers’ interests?

When potentially popular and effective resolutions appear, they are frequently watered down inside policy papers to give the appearance of democratic process while keeping the lid on things.

Waste of scarce resources

Conventions are financially costly. For a CLC convention, delegates fly in from across the country and typically book one delegate per costly hotel room and receive generous per diems for meals. Imagine what kind of organizing and support for real struggle and change there could be were we a little more frugal, creative, and long-sighted. Meanwhile, labour organizers in the Global South often seem to be able to consistently do more with less, while producing far more effective results.

According to David Camfield, associate professor in labour studies at the University of Manitoba and author of Canadian Labour in Crisis, “it’s worth noting that in many cases the people who attend as delegates aren’t the best activists, the ones who are troublemakers on the job, supporters of community struggles, and critics of complacency in the unions. Such activists often aren’t delegates, either because they don’t get elected or – in unions where delegates are selected, not elected – because officials deny them delegate credentials. Some people on the left think conventions are the most important moments in the life of a union. I disagree, for two reasons. First, conventions often don’t have that much impact on what happens in the union. For example, if a resolution gets passed that the top brass don’t like, they can often find a way to ensure it never gets acted on. Second, unions matter most when ‘union’ means workers taking action together in the workplace or on the streets.”

What now?

What is the purpose of a labour convention? I would argue that it is to challenge the growing capitalist disaster with a strong and vibrant force of organized workers, both unionized and non-unionized, including the unemployed and underemployed.

Labour centrals and organizations need to stop spending significant amounts of members’ dues money to stage events that maintain the status quo and privilege a few at the expense of the many. The International Trade Union Confederation, CLC and provincial federations of labour have proven themselves to be lacking vision, which robs workers while reproducing a labour aristocracy void of ideas for these times. It is time for critical questions and tough self-reflection.

What is unclear is how trade unions intend to challenge the austerity agenda. Merely coping, hanging on, and focusing a great deal of energy on electoral politics at the expense of other forms of struggle will not be enough to overcome the challenges that lay before us. Given the state of the current economic arrangements, it’s probably safe to say that it won’t serve future generations well either.

What is to be learned from our history? Labour movements and the victories gained from them were not built by “urging” and “lobbying.” They were created by the collective dignity and expression of human beings who took risks and action against capital. What can be learned and applied from autonomous, anti-capitalist, anti-colonial, migrant, Indigenous, student, and social movements that might shift this theatre of empty rhetoric and surrender to create a coordinated body of workers prepared to take the offensive, not just in the present, but for future generations?

The questions to be asked are not about Harper and the corporations. The questions to be asked are of us.