*Author’s note: With the exception of Jason Devine and Bonnie Collins, all anti-racist activists quoted in this article have been given pseudonyms. The writer’s name has also been changed. The reason for this should be obvious: neo-Nazis are dangerous, and those who organize to stop them put themselves at risk.

Even more dangerous than neo-Nazis, though, is the prospect that the actions of a few extremists could distract attention from the systemic discrimination and violence that indigenous peoples, people of colour and queer people (to name just a few of our society’s marginalized groups) encounter every day.

Blatant racism may infuriate or disgust us, but so too should elevated rates of poverty, violence, and poor health among members of oppressed groups-the real-world consequences of systemic racism and discrimination. Neo-Nazi organizing in our communities demands our attention, but so do these more subtle, but far more widespread manifestations of racism.

Jason Devine and his fiancée Bonnie Collins live with their four sons, ages three to nine, in a cluttered townhouse on a quiet side street in Calgary. Both Devine and Collins are active members of the Communist Party of Canada and Anti-Racist Action (Calgary). On February 12, 2008, while the boys slept upstairs, Devine heard a crash and saw a flash outside his kitchen window. He knew immediately that someone had thrown a firebomb at his house.

Luckily, the Molotov cocktail was poorly constructed and most of the gas burned up in the air between the back fence and the corner of the wall it struck. No one was hurt and property damage was minimal, but the message was clear, at least to Devine and Collins. Their anti-racist organizing had drawn the ire of local racist skinheads.

According to media reports at the time, the police suspected neo-Nazis in both this and another firebombing that occurred earlier the same day in another part of Calgary. Though no one has yet been charged, Devine is convinced the attack was undertaken by members of the Aryan Guard, a white supremacist group that had recently set up in Calgary.

To Devine, the only surprise about the attack was that it was so long in coming. “I’ve been waiting for it since Western Canada For Us.”

Western Canada For Us (2004)

Founded in 2004 by Glenn Bahr and Peter Kouba, Western Canada For Us was an Alberta-based group founded on the ideology of white nationalism, which the white nationalist website Stormfront defines as “protecting” white people from being “snubbed” by “burdensome racial preference schemes in hiring, racial preference schemes in university admissions, racial preference schemes in government contracting and small business loans.” White nationalists commonly place blame for any social ills (crime, unemployment, poverty) on non-whites. They blame Jewish conspiracies for controlling government, the media and educational institutions, and they are also generally disdainful of queer people, people with disabilities, and leftists. While they claim to be “proud, not prejudiced,” posts made by Bahr to online forums make this assertion hard to believe: according to Bahr, First Nations people are “vermin” and all homosexuals’ lives should be “terminated.”

Western Canada For Us was very active during the few months it existed. Between January and May 2004, members organized a meeting in Red Deer, which was attended by notable neo-Nazis Paul Fromm and Melissa Guille. They also held a rally in support of Holocaust denier Ernst Zundel and operated a popular website and forum. However, all was not well within the organization. Power struggles split the group and Bahr became the target of an aggressive campaign initiated by Anti-Racist Action (Calgary). After being exposed as a neo-Nazi to his neighbours and employers in early March, 2004, Bahr lost his apartment and job in Red Deer and moved to Edmonton. In May 2004, police raided his home and seized numerous items bearing Nazi symbols, including two computers that were hosting the Western Canada For Us website. This seizure effectively dissolved the group, after which Bahr moved back to his parents’ home in Langley, B.C., to await his 2005 trial for promoting hatred and a 2006 appearance before the Canadian Human Rights Commission. This commission found Bahr and Western Canada For Us guilty of violating the Canadian Human Rights Act prohibition against distributing hate propaganda through the Internet. Each was fined $5,000 and ordered to cease the discriminatory practice.

Because Devine was the public spokesperson for Anti-Racist Action (Calgary) and was named as the group’s “leader” on white nationalist websites (even though Anti-Racist Action is non-hierarchical), he was an obvious target. Anti-Racist Action (Calgary) had not only cost Bahr his home, livelihood and freedom, but had also shut down a white supremacist group that seemed to be gaining ground. Devine’s name and image were familiar to racist organizers, so it was a fearful time for him. “I’d wear my winter coat in the summer with the hood pulled up. The cops would look at me weird, but whatever. I didn’t want [the racists] to recognize me and follow me home.”

After the dissolution of Western Canada For Us, things got pretty quiet-at least until late 2006. That’s when the Aryan Guard marched into town.

“The rally was met with fierce resistance, with approximately 200 anti-racist demonstrators pursuing a few dozen Aryan Guard members and supporters through downtown Calgary.”

The Aryan Guard (2006-present)

Living in Kitchener, Ontario, Aryan Guard founder Kyle McKee and his roommate Nathan Touchette gained notoriety by flying a Nazi flag outside of their apartment. In April 2005, upon hearing the two men were interested in moving to Alberta to take advantage of the hot economy and labour shortage, Calgary mayor Dave Bronconnier told them to “stay home.” They didn’t.

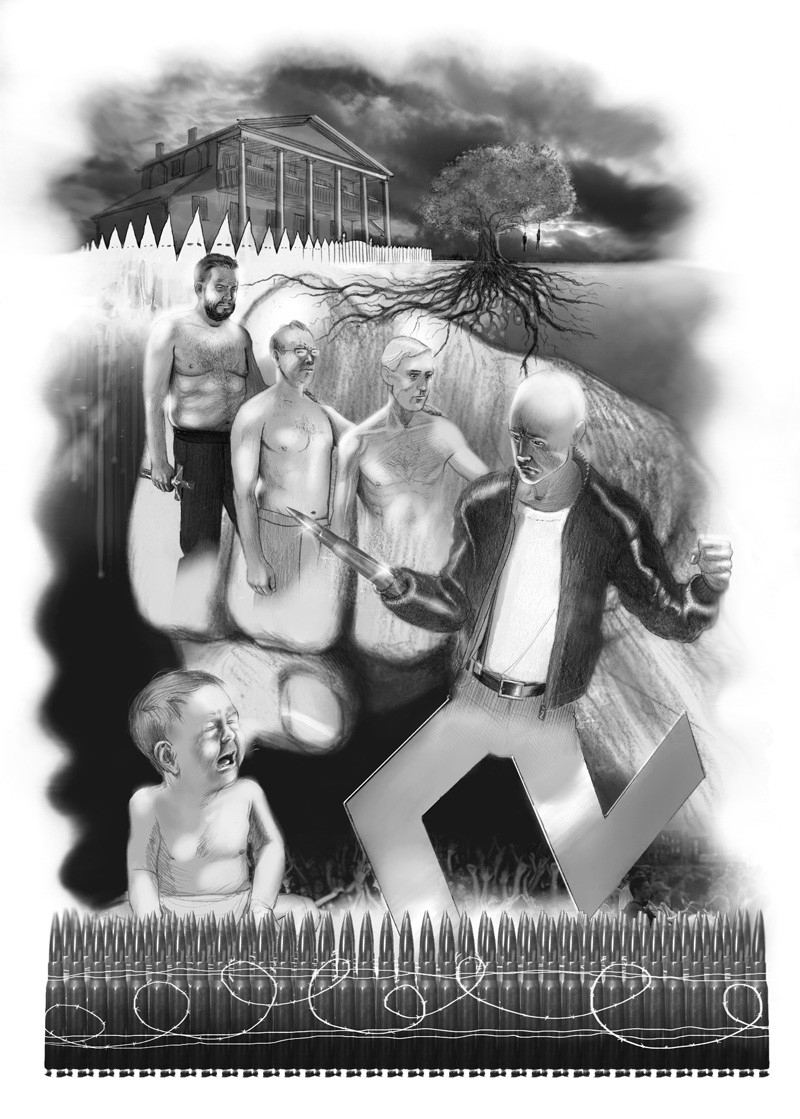

The Aryan Guard formed as a group in late 2006, primarily recruiting and organizing via the Internet. Founders McKee and Dallas Price put out calls to fellow Calgarians on white nationalist websites like Stormfront and held their first meeting on March 21, 2007, a date widely known as the United Nations International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination that has also been declared “White Pride World Wide Day” by white supremacists. The next time the group came together was April 20, 2007, when they celebrated Hitler’s birthday with dinner, drinks and a swastika-shaped birthday cake.

Since then, members of the Aryan Guard have put up posters, handed out leaflets and responded to anti-racist rallies with their own protests. They hold regular meetings and continue to use the Internet to recruit and organize. Their numbers, judging by public appearances, have grown from approximately 15 in October 2007 to 40 in March 2008. The Aryan Guard uniform-shaved heads, jackboots, tattoos, swastika and SS T-shirts-is becoming a fairly common sight around Calgary.

“A year ago, it would be rare to see these neo-Nazis walking around,” says “Bernard,” an anti-racist activist from Calgary. “Now you can find them on buses and trains, in parks and at bars. They’re all over the place now and their numbers are growing.”

The Aryan Guard organized their first public protest in August 2007 as a counter-protest to an anti-racist march. Since then, they have organized a demonstration against Muslim women’s right to wear head coverings when voting and a “White Pride World Wide” rally in March 2008. The rally was met with fierce resistance, with approximately 200 anti-racist demonstrators pursuing a few dozen Aryan Guard members and supporters through downtown Calgary. Heavy police presence ensured that the confrontation didn’t escalate beyond a heated screaming match.

The Aryan Guard’s mandate is based on the “14 words,” a phrase coined by David Lane in the 1980s while he was serving a 190-year sentence for racketeering, conspiracy and the 1984 murder of journalist Alan Berg. The “14 words” read “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for White children.” The group claims to be family-oriented and opposed to violence and illegal activities. They say that they are “White Pride,” not “White Power.”

Anti-racists don’t buy it, though. “White Pride is clearly and solely a euphemism for hatred,” Devine says. Their website “is completely disingenuous. They say they’re non-violent, but they pose with weapons. These people have violent tendencies, at the very least.”

Bernard agrees. “I would classify them as racist terrorists. They use fear tactics to spread their political beliefs.”

If videos posted on the Anti-Racist Canada blog are any indication of the kind of non-violent family values the Aryan Guard espouses, Devine and Bernard have a right to be skeptical. In a profanity-laced diatribe, Aryan Guard member Jason Harley explains that multiculturalism is like putting a red sock “representing the communists” and a blue sock “representing the Jews” into a washing machine with a white load of laundry. “Everything turns fucking fruity and purple and fucking gay. Fucking retarded. There you go. Fucking white supremacy.” In another video, two Aryan Guard members fight bare-chested in the snow on a quiet residential street.

““It had never happened before that people were being jumped for the colour of their skin. I pretty much stopped going downtown. It didn’t feel like my hometown anymore.”

The Final Solution (1989-92)

Intimidation and violence by racists is nothing new to Alberta. The province has a history with the Ku Klux Klan that dates back to the 1920s. Neo-Nazi skinheads, their rhetoric and their uniforms are not new, either.

Between 1989 and 1992, a group of skinheads calling itself the Final Solution (referring to the Nazi plan to exterminate the European Jewish population during World War II) moved into Edmonton and brought with it a culture of fear and violence.

“They seemed to appear overnight,” says “James,” a former member of the Anti-Fascist League, which was active in combatting the spread of racist propaganda and violence at the time. “A couple of them landed in Edmonton and next thing you knew there were 15 to 20.”

“They were quiet at first,” he adds. “I think they came to Edmonton because there was no history [of skinhead activity] here and they were getting run out of other towns. I think they probably told themselves that no one was paying attention so they didn’t want to fuck it up. But you get a few drinks in them and they’re a pack of rabid wolves. If they were out drinking and someone of a different colour looked at them the wrong way, that was it.”

According to James, once Daniel Sims arrived in town and Terry Long started funding the group sometime in 1989, it became a movement. They began actively recruiting, organizing and distributing propaganda. Sims and Long are infamous in white supremacist and anti-racist circles alike. Sims was one of two neo-Nazi skinheads who brutally attacked journalist Keith Rutherford on his doorstep in 1990, leaving him blinded in one eye, while Long was the leader of the Aryan Nations in Canada and a father figure to many young skinheads, allegedly providing money, training and literature for their membership drives and campaigns. Long was brought before the Alberta Human Rights Commission in 1991. When served with a notice of claim on behalf of Rutherford, he skipped the province and went into hiding-first in California, then in B.C.

“One thing that’s important is how it changed the city,” James says. “It had never happened before that people were being jumped for the colour of their skin. I pretty much stopped going downtown. It didn’t feel like my hometown anymore. I had never felt unsafe before, but it really split the community.”

In an effort to clear their city, anti-racist organizers launched a three-pronged campaign. According to “Jean-Claude,” a long-time anti-racist activist, “We had three main focuses. One, know as much as possible about them. Two, make their lives as uncomfortable as possible. Three, target substitution.”

The tactics Jean-Claude refers to have been used by Anti-Racist Action organizers since the early 1980s. Using the information they’ve gathered, anti-racist organizers let the leaders’ co-workers, schoolmates, neighbours and friends know about the person’s racist beliefs and activities through posters, flyers and phone calls. Then they try to make themselves the focal point of the group’s frustration. As Jean-Claude puts it, “get the racists focused on us instead of random taxi drivers.”

“Back then, you could find out whose name was on, say, the phone bill,” says James, referring to the days before PINs and security questions. “You could phone EdTel and say you were so-and-so and you were moving to Vancouver tomorrow so could they cut off your phone service-and EdTel would.”

The climax of the campaign happened in the summer of 1990 when about 50 anti-racists gathered in downtown Edmonton to blanket the city centre with posters. Within a few minutes, however, police seized their supplies. So they got on their walkie-talkies and decided to gather again.

“We were standing around wondering what to do,” says James. We had all these people and we were all riled up. Then someone said, “˜Let’s go to their house!’ So, we appointed a couple of spokespeople, gave everyone else instructions not to shout or say anything, and went over” to a popular white supremacist hangout known as the “Skin Bin,” the downtown home of several Final Solution skinheads.

According to James, the anti-racists gathered on the sidewalk while the neo-Nazi skinheads levelled shotguns and made it very clear what would happen if the anti-racists set foot on their property. The spokespeople and neo-Nazis argued, but James said it was a calm exchange. In the end, the anti-racists’ main point was made. Racists weren’t at all welcome in Edmonton.

“It took about a year,” says James. “When they did leave, though, they left pretty quick. They must have realized that they could get their asses kicked to Vancouver and back. Between that and their electricity, water and phone being cut off, I think they were getting uncomfortable.”

““˜We had three main focuses. One, know as much as possible about them. Two, make their lives as uncomfortable as possible. Three, target substitution.’

The shelf life of a neo-Nazi

It’s widely agreed that most neo-Nazi skinheads are youth. Even the most cursory investigation of the membership of groups like the Aryan Guard and its predecessors supports this perception. McKee, for instance, is 23 years old. Most other Aryan Guard members and supporters are under 30.

“A lot of them were from less-than-ideal situations,” says James, referring to the Final Solution skinheads he encountered. “They were introduced by kids their own age, but groomed by older men-father figures who were drastically missing from their lives.”

Jean-Claude is quick to point out that perhaps the reason that most of the members of the Aryan Guard are so young is that “the average “˜shelf life’ of a neo-Nazi is one to three years.”

“Harry,” who was heavily involved in the punk and skinhead scene during the Final Solution era and friendly with many of the skinheads, agrees. “The ones who were really hard into it either moved away or were thrown into jail.”

Daniel Sims is perhaps a perfect example. Once the most prominent Final Solution skinhead and, according to James, “one of the few who scared me because he was a lifer,” Sims has spent several years in prison in both Canada and the U.S. Sims has recently disavowed his involvement with neo-Nazi skinheads in television and magazine interviews.

As Sims puts it, “they put themselves on the fringes of society by choice.” This isolation from the mainstream coupled with aggressive anti-racist campaigns seems to cause young recruits to eventually burn out or bow out, particularly when key members are imprisoned or forced to move due to hostile conditions.

What’s next?

Since the March 21, 2008, rally, the Aryan Guard has been fairly quiet, but members are still active on Stormfront and there has been talk of creating an Edmonton branch of the Aryan Guard. Meanwhile, anti-racists across Alberta are putting their heads together on how to drive the new crop of white supremacists out of their province. They are exchanging information and keeping each other abreast of developments in their respective cities.

“Leaving them alone is not an option,” says Devine. “We can’t just sit around and wait for the police, because essentially the police’s hands are tied. It’s not a crime to hate Jews or Blacks or whatever. Until you say “˜Jews are all evil and need to be killed,’ it’s not a hate crime. Until they break the law, it’s our job to alert the community.”

“We show up to let them know that we’re watching them and that the community doesn’t have to be afraid,” he says.

Devine’s community isn’t alone. Cities across Canada, in fact, are affected by white supremacist groups. Saskatchewan is home to the Brotherhood of the Klan and the Saskatchewan Aryan Nations. Ontario has the Canadian Heritage Alliance and the Northern Alliance. Stormfront members come from every corner of the country. Members of these groups know each other, attend each other’s events and move from city to city. Calgary is just the most recent gathering place, largely due to economic and political conditions.

“Alberta is generally pretty right-wing,” says Bernard. “On top of that, there’s the boom, so it makes it a hotbed for anyone trying to make money, which includes neo-Nazis.”

If anti-racists have their way, though, the neo-Nazis won’t stay in Alberta for long. Unfortunately, that means they may soon be attempting to regroup in your community. Anti-racist activists believe that if you maintain a vigilant anti-racist stance, they won’t stay for long.

Ava McDougall is a freelance writer and activist based in Alberta. She has several publication credits under her real name, but this is her first-and hopefully last-published under this pseudonym. Due to personal safety concerns, that’s all the information she’s willing to provide.