“Here, we have Dutch cannabis, Moroccan hash, and Lebanese red hash.”

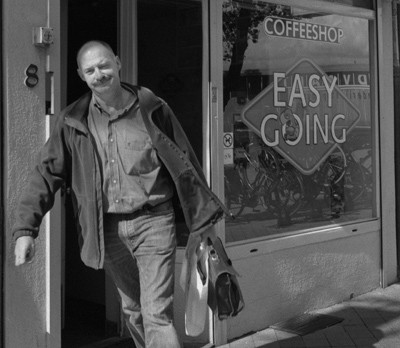

Pieter van der Camp gestures to the neatly packaged, labelled, rolled and ready-to-smoke cannabis products that are his stock-in-trade. He is owner of the marijuana coffeeshop Pas Op! (Watch Out!) in the picturesque municipality of Schiedam on the outskirts of Rotterdam. Coffeeshops like Pas Op! are now at the centre of a national debate about legalizing the growing of cannabis. Though the sale of marijuana through coffeeshops has been quasi-legal in the Netherlands for 30 years, the “backdoor” supply of the drug has remained illegal.

“The average age of my customer is between 30 and 60,” Van der Camp tells me. “In the evening younger people come to hang out and play pool. I used to own a pub, but in this business I make more in one hour than I did all night selling alcohol.

“The clientele is a lot quieter too.”

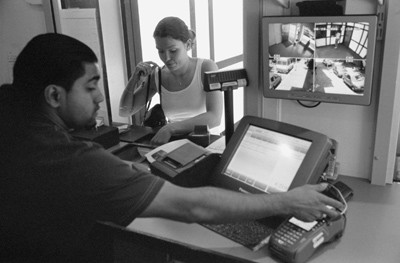

Most of Van der Camp’s customers opt for take-out. He proudly points out his identification system, which he imported from Canada where it’s used in shopping malls. Coffeeshop owners can be put out of business for selling cannabis products to minors or for making repeat sales to the same customer in a single day.

The Netherlands is the only country in the world to allow over-the-counter sale of cannabis products. In the 1970s, when cannabis was becoming the drug of choice of young people in the Netherlands, for reasons of pragmatism and public health the Dutch government amended the Opium Act to distinguish soft drug use from hard-drug use and, deeming cannabis no more risky than alcohol, created the coffeeshop system. The first coffeeshop in Amsterdam, Mellow Yellow, opened in 1972.

Cannabis coffeeshops are the most highly regulated businesses in the Netherlands. Profits are taxed at 52 per cent. Regulations include having no more than 500 grams on the premises at any one time, selling a maximum of five grams per customer, not selling to minors, educational courses for staff, no advertising and no hard drugs. Spot checks by police once or twice a week are the norm. If coffeeshop owners are found negligent, they can lose their license-a severe punishment in this highly lucrative business.

Locally grown marijuana, known as Nederwiet, has largely displaced imported hashish and marijuana. Dutch smokers prefer the higher THC content of local bud compared to foreign products. Today more than 80 per cent of cannabis sales in coffeeshops is of Dutch origin.

“I am a model coffeeshop owner,” says Van der Camp. “I belong to the local business association here in Schiedam.” When we leave his shop to visit his marijuana sorting operation across town, I comment on the beautiful hanging baskets gracing the cobblestone street outside of Pas Op!, which Van der Camp says he maintains and waters for the area on a volunteer basis. “After all,” he adds with a wink, “I am interested in plants.”

Gedogen and the Dutch art of drug regulation

To better understand how the regulation of the coffeeshops works, I pay a visit to Wouter de Jong, the tall, willowy project manager of cannabis education for the Municipal Health Service in Rotterdam. De Jong is employed to write materials and organize educational seminars for owners and coffeeshop employees, who must be certified in order to work in a coffeeshop. I had first met him a year ago at the International Harm Reduction Conference in Vancouver.

“People are allowed to grow up to five plants for personal use in the Netherlands,” he tells me, but many people prefer to buy from the coffeeshops. Historically, the Netherlands was home to a number of tribes and regions, de Jong explains. In order to ensure social harmony among these disparate groups, the state never became very centralized as it evolved, instead fostering a culture of negotiation and compromise. In Dutch, this attitude of social tolerance and flexibility is called gedogen.

A good example of gedogen at work is the “opportunity principle,” an element of Dutch law that has allowed the Netherlands to circumvent its obligations to international drug conventions to which it is a signatory. According to the opportunity principle, the Minister of Justice can decide whether or not to prosecute certain misdemeanours within criminal law. For three decades, Dutch lawmakers have simply chosen not to prosecute the owners of the coffeeshops.

This system has proven to be very practical for the Dutch. They have avoided the costs of criminalizing users, while the taxes on coffeeshops more than pay for the cost of supervising them.

“Cannabis is not candy,” says de Jong. “Generally people smoke in their free time, but it can be abused like other drugs. Here in the Netherlands we can talk openly about these things. Nobody is afraid of losing their job, going to jail, etc. The best thing about the coffeeshop system is that it reaches out to cannabis users. We can have an impact on their behaviour.”

In the municipality of Rotterdam, for instance, the addiction centre and the association of coffeeshop owners have worked together to develop a professional health education policy that is being implemented within the 61 coffeeshops in the city.

“However,” de Jong continues, “the problem of supply of cannabis to the coffeeshops has never been solved. What we need to do now is create a licensed system of marijuana plantations. “We need to take the supply to the coffeeshops out of the “˜dark zone’ and regulate it and tax it like we do the coffeeshops.”

Since the l970s, coffeeshop owners like Van der Camp have had to contend with the fact that while selling marijuana over the counter at the “front door” is quasi-legal, the supply of cannabis to the “back door” is not.

This creates a situation that requires a heavy dose of gedogen. Because only 500 grams of cannabis products are permitted on the premises at any one time, bicycle couriers often deliver marijuana several times a day. Needless to say, the police aren’t hanging around the back door waiting for deliveries, so things have functioned in this “nudge, nudge, wink, wink” fashion for decades.

Maastricht’s mayor calls for legal grow ops

In the Netherlands, municipalities are in charge of coffeeshop policy. The mayor’s office decides how many coffeeshops will be licensed and where they will be located. One mayor in particular has become a household name in the Netherlands of late for his radical stance on coffeeshop policy. I travel by train to Maastricht, a medieval university town in the south of the Netherlands, to interview Mayor Gerd Leers, who is openly campaigning for supervised, controlled cannabis plantations to supply the coffeeshops and is petitioning the central government in The Hague for permission to start trial plantations in his jurisdiction.

Maastricht is best known for the Maastricht Treaty of l992, which led to the creation of the European Union. Located between Belgium and Germany on two major highways, it has become a hot spot on the international map of drug tourism. This may be good for the local economy (and for visiting students relaxing after exams), but it has also led to an increase in crime and public disorder and a mushrooming of underground cannabis grow ops. Tourists not only want grams but kilos of the stuff. Residents are complaining.

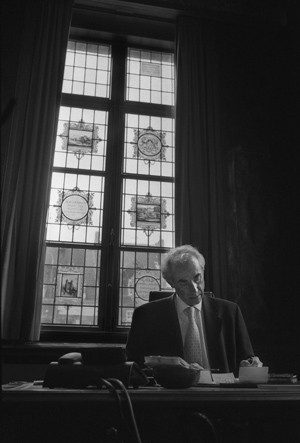

Waiting in the majestic 17th-century-stone city hall in Maastricht for my appointment with the mayor, I am given a tour of the wedding room by the concierge. At last, Gerd Leers appears, a stern, white-haired towering figure of a man who looks like he could have stepped right out of a Rembrandt. He seems an unlikely champion of marijuana plantations. We sit at a round table in his office, surrounded by stained glass windows and chandeliers.

“I am not in favour of cannabis,” he says with a frown. “I am not in favour of drugs generally, but if people are going to use them, then we either use harsh repression or we regulate them to overcome criminal activities.”

“We have to modernize our policy,” continues Leers. “Our failure to control the “˜back door’ means that we are getting more criminal activity around the cannabis trade. If you control the front door you have to control the back door as well, because otherwise you play into the hands of criminals. If you continue to permit the sale of cannabis, it has to be supplied from somewhere.” Under Leers’ proposal, “bona fide growers will have to pay taxes and employee social security contributions. We oversee their operations.”

“The enormous influx of drug tourists coming over the border-about 3,000 per day-is attracting illegal dealers, mostly from North Africa and Turkey, who are trying to cash in on the large number of students and tourists visiting the coffeeshops,” Leers explains.

This is a big problem for the Maastricht police, who are now dealing with drug gangs from as far away as Russia.

Over strong Dutch coffee in his tiny office, Piet Tans, spokesperson for the Maastricht police force, tells me that “the proliferation of outside dealers is something we have to solve. We are looking for a socially designed answer because the illegal trade is costing us too much in police manpower.”

“To ignore the problem is an “˜ostrich’ policy and it doesn’t work,” says Tans, who is proud of his government’s drug policies. “In the Netherlands we have fewer deaths from drugs than other countries. We consider cannabis a soft drug with acceptable risks. We can check on the coffeeshops-we can control them. We have a helicopter view on their activities. Maybe the Germans and the Belgians have to open up coffeeshops and then regulate them. Holland is waiting for the next step of these countries.”

Like Leers, Tans thinks supervised plantations might be a solution. “We close down a hundred grow operations in this area every year but they spring up somewhere else-the waterbed effect. We have to go the next step and no longer ignore reality.”

“The Mayor has asked [for permission to grow cannabis] and the Minister of Justice and External Affairs refused, but he can try again with a new government.”

Political life in the Netherlands sometimes takes surprising turns. As part of his campaign for supervised marijuana plantations, Mayor Leers made a rap video with one of Holland’s most popular punk bands, de Heideroosjes, called “Da’s Toch Dope Man!” It played all over the country. Not to be outdone, the Dutch Minister of Social Affairs, Piet Hein Donner, who had nixed the idea of trial plantations when he was Minister of Justice, made a rap video of his own where he goes around with a group of policemen sniffing marijuana plants and shaking his head.

“Stoned people are easier to control”

Marc Josemans, owner of Easy Going, one of Maastricht’s most popular coffeeshops, is late for our appointment-but it’s not what you think. He was called in unexpectedly to meet with Mayor Leers. I want to talk to him because he is the president of the local association of coffeeshop owners which is very much in favour of legalized marijuana plantations.

I pass the time talking with customers crammed into tiny booths, mostly students from France and Belgium celebrating the end of exams, who were drawn in by the logo on the front window of a happy turtle with a big joint.

“We would like to have coffeeshops in our country,” says Noemie, one of three veterinary students from the University of Liege, “but Belgium is very old-fashioned. We are only allowed to possess three grams. We don’t even have medical marijuana. We are on a bit of a spree after exams, and it’s only 20 minutes away by train. You don’t have to worry about the police here, and Nederwiet (Dutch cannabis) is very safe.”

Abdul, a young, glum-looking Moroccan, is just lighting up a joint. “I come here every day to smoke hashish,” he tells me. “I’m unemployed and depressed. I hate to do it but it’s the only friend I have in this town.”

Andy, an American serviceman from Michigan stationed in Germany, has another take on things. “The Dutch are a passive-ass, Buddhistic, decadent society,” he says. “Next to Germany they have the longest record of being communistic and Marxist. That’s why they have these coffeeshops: stoned people are easy to control.”

When I ask him why he is here smoking pot if he holds such views, he replies that marijuana was his first love as a kid and he was weak. “I would like to be part of society,” he says. Then he starts muttering something about global warming, farm tractors and homosexuals.

I am rescued by Marc Josemans, owner of the coffeeshop, who has just returned from his meeting with the mayor. We go to his upstairs office.

“I see myself as a serious entrepreneur,” Joseman says, rolling himself a large joint mixed with tobacco. “I have been in the business for 23 years. My license is very valuable. We coffeeshop entrepreneurs are more rare than astronauts. There are only 760 of us on the planet.”

“I have good relations with the mayor,” he says. “The coffeeshop owners have the best idea of how to solve problems. Our mayor is a fine example of working together.”

“We came that close to having the supply problem solved,” continues Josemans, holding up his thumb and index finger an inch apart. He is referring to the June 2006 vote in the Dutch parliament that saw the introduction of trial cannabis plantations narrowly defeated. “We came very close. I was sure it would happen. But when the Minister of Justice, Piet Hein Donner, threatened to resign, the whole thing fell apart.”

The June 2006 vote on trial plantations neatly illustrates the contradictions in Dutch cannabis policy. In the mid-‘90s, because of intense pressure from the international community (notably the United States and France), the Dutch government agreed to comply with its international obligations to fight illegal substances, including cannabis. Since then there has been a dramatic decrease in coffeeshops in the Netherlands, from 1,500 ten years ago to fewer than 800 today.

This trend worries de Jong, project manager of cannabis education in Rotterdam.

“There seems to be a new moral movement here in the Netherlands,” he says. “We wouldn’t be able to create the coffeeshop system in the political climate we have now. The theoretical basis of the Dutch coffeeshop system is rather weak, so we are vulnerable to changes in the political arena. Our current prime minister, Jan Peter Balkenende, says he does not accept cannabis as part of “˜Dutch values’.”

“In the Netherlands it will be hard to turn the clock backwards. That some people smoke cannabis is an accepted part of Dutch culture now,” he adds.

The “green avalanche”

Though Dutch politicians are not about to publicly defend the coffeeshops as a pillar of national cultural heritage any time soon, there are still a lot of reasons to expect the coffeeshops to survive the current climate of repression. Many mayors, worried about illegal dealers, are resisting further reductions in coffeeshops. There seems to be a tacit understanding between the Association of Cannabis Retailers and the mayor of Amsterdam (and an overwhelming majority of city councillors) that the number of coffeeshops will not decline.

Gerd Leers, the outspoken mayor of Maastricht, is not the only mayor calling for controlled cannabis plantations. For almost 10 years politicians in the provinces have been trying to convince The Hague to allow them to solve “the backdoor problem” of the coffeeshops. The Freedom to Farm campaign of ENCOD, the European Coalition for Just and Effective Drug Policies, is lobbying for the decriminalization of Eurocannabis production for use within Europe. And recently the European Commission explicitly acknowledged the right of member-states to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of marijuana for personal use.

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime meets in Geneva every 10 years. At the last meeting in 1998, under pressure from the U.S. and its “war on drugs,” UNODC resolved “to rid the world of [all] drugs by 2008.” In the intervening years, this approach has failed completely, giving more weight to the anti-prohibitionists. This December, a group of prominent Dutch politicians, including former prime minister Dries van Agt, as well as former ministers of health (Els Borst) and internal affairs (Thom de Graf), the mayors of Maastricht, Nijmegen and Tilbur, a Green Party member of the European Parliament and three chiefs of police met in The Hague to formulate a proposal for the 2008 UN Conference on Drug Policy recommending a more tolerant soft-drug policy.

Dr. Adriaan Jansen, a researcher on cannabis issues at the Faculty of Economics at the University of Amsterdam, believes that Europe is moving closer to solving the cannabis issue by considering it a local rather than an international affair-and that the “green avalanche” of cannabis production in the Netherlands and other countries will eventually bury the wall of prohibition.

“Twenty-five years of experimenting with the coffeeshops has brought us to a point of no return in matters of cannabis,” says Dr. Jansen. “The coffeeshops have shown that a civilized way of dealing with cannabis in the real world is possible. Now it’s just a matter of economics.”

The Dutch experience has shown that decriminalization does not necessarily lead to increased drug use: the Dutch are toking up less than the French, the British, the Germans or the Americans. And Canadians in particular could learn a thing or two from Dutch gedogen: according to the 2007 World Drug Report of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, Canadian youth smoke twice as much as Dutch youth and Canada leads the industrialized world in cannabis use, when calculated as a percentage of population.

Calls for the decriminalization of marijuana use in Canada have found some unlikely allies. Following upon several similar recommendations dating back to the 1970s, the 2002 Canadian Senate Report on Illegal Substances recommended the decriminalization and regulation of cannabis as a way to mitigate the considerable social and economic costs of prohibition. In spite of intense efforts by the Harper government to scare Canadians into believing that cannabis is a hard drug, a June 2007 Angus Reid poll reports that 55 per cent of Canadians think marijuana should be decriminalized.

Meanwhile, in the absence of regulation and a social framework for cannabis consumption, the cannabis market in Canada is making a lot of questionable people rich. A recent report from the RCMP reveals that Canada’s marijuana trade (nearly half of which is based in B.C.) is worth about $7.5 billion annually and is connected to weapons and explosives trafficking, cocaine smuggling and stock-market fraud.

Postscript

Recently, coffeeshop owners had a bit of a fright when the government in The Hague announced a smoking ban in restaurants, cafes and pubs to come into effect next year.

“We were very relieved when the Health Department told us that the ban will be anti-tobacco only and not apply to cannabis smoke,” says Marc Josemans of Easy Going. “We will have to stop mixing tobacco with our cannabis and start using vaporizers like you do in Canada.”

Elaine Brière is a Vancouver-based documentary photographer, filmmaker and writer who is happy to be back in the Briarpatch once again.

View the rap videos of Gerd Leers and Piet-Hein Donner.