Sarah Ovens starts off our conversation recollecting Raffi Balian’s legacy. “He was really one of the grandfathers of harm reduction in the city […] and also one of the most brilliant people I’ve ever known,” she says.

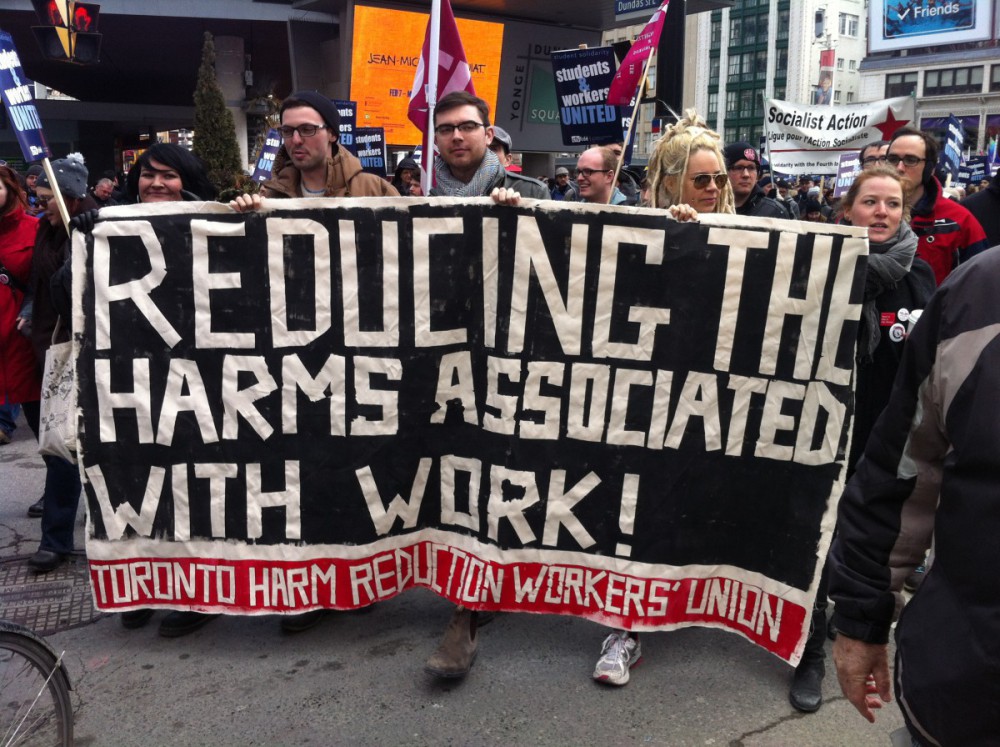

Ovens was a founder of Ontario’s first supervised consumption service – the initially unsanctioned Moss Park Overdose Prevention Site – and a member of the now-defunct Toronto Harm Reduction Workers’ Union (THRWU). Balian, the man she speaks about, helped start the harm reduction program at the South Riverdale Community Health Centre and was himself an active drug user. He played a large role in building the peer programs that became a cornerstone of harm reduction work.

“[Balian] was one of the people that really had motivated the starting of the [THRWU],” Ovens explains of the world’s first harm reduction union, self-organized by harm reduction workers across the city. The last X activity by THRWU, which mourned the loss of Balian in February 2017, occurred shortly before its own folding – a foreshadowing of the difficulty of this type of labour organizing which is stymied by provincial policy that fans the flames of the toxic drug supply crisis.

Raffi Balian pictured at one of the THRWU forums in 2014. Photo by Sarah Ovens

Forming THRWU

The THRWU, formed in 2014, was affiliated with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Founded in 1905, the IWW organizes across industry rather than by individual workplaces and started with the organization of “unskilled workers” – because unions at the time only organized people considered skilled labourers, offering other workers no chance at protection from egregious working conditions.

Matthew Tracey, a PhD candidate in health policy and founding member of THRWU, speaks of three core tenets that informed the IWW: if workers are in solidarity across a sector, it’s more difficult for employers to divide workers and continue business operations; the IWW aims to be democratic in its structures (e.g. voluntary dues); and the IWW is attuned to direct action. In 2013, the IWW showed up in solidarity with a unionized group of fuelers at Porter Airlines. Workers were blockading the entrance of the airport and other transportation routes to the airport to cause flight cancellations. This direct action participation and emphasis on solidarity in the IWW influenced some of the THRWU founders toward this model of unionization.

Tracey explained that THRWU’s creators used pre-existing connections to develop THRWU – many of the members were also involved with the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty – and hosted meetings to collaborate on what an appropriate model looked like for the organization. Jordan House, an assistant professor of labour studies at Brock University and member of THRWU, recalled mapping and charting – a conventional union organizing strategy – to determine where the harm reduction workers were in the city, and who was sympathetic to their campaigning. On November 11, 2014, workers from both the South Riverdale and Central Toronto community health centres informed their employers that they were a part of THRWU. In December 2014, THRWU was formally announced to the world as the world’s first harm reduction workers’ union.

Some of the issues they wanted to address were discrepancies in wages, access to basic health benefits that workers needed, and ending discrimination against workers due to the lived experience for which they were hired.

Why a grassroots union?

THRWU worked to address the gaps left by traditional unions that left some front-line workers exposed to unaddressed workplace grievances. Their composition also differed from that of traditional unions – it included volunteers, part-time and casual workers, and full-time staff. There were no limitations on who could be a member.

Despite the institutional emphasis on hiring people with lived experience of drug use – it looks good for organizations that offer health services to claim they are employing people with this lived experience – these employers don’t offer, nor do their unions advocate for, positions that accommodate the lived realities of people actively using drugs.

THRWU also had tiered membership dues to account for varying wages – dues were based on the level of your income, but nobody was left out of the system. In 2014, they held a GoFundMe campaign that raised $4,066, with notable donations from IWW chapters around the world.

They also addressed workplace grievances on a case-by-case basis with direct action being their tool of choice. Rather than union stewards, they had worker councils at each workplace. No collective bargaining agreements were administered by THRWU.

These were conscious choices made in recognition of the failure of traditional union structures to address the unique needs of individuals with substance use struggles, which can lead to further instability in their employment. Although there are supposed legal accommodations for this, their practical implementation is lacking. Employers in Canada have a duty to accommodate and adjust rules, policies, or practices so everyone can fully participate in the workplace, but workers aren’t always afforded the accommodations they may need. As a long-time peer support worker who asked to remain anonymous for fear of job reprisal shares, “If you're going to have [workers] with lived experience, you've got to be able to have the patience to talk to them, to show them ‘this is what you can do; this is what you can get.’ Nobody did that with me.”

Mskwaasin Agnew, Anishinaabemowin for Redstone, a Cree and Dene and a band member of Salt River First Nation and a harm reduction worker at Toronto Indigenous Harm Reduction agrees. “[Peer workers] are doing grueling front line work. It's not easy, and there's no support for grief."

Active drug users may need additional work accommodations. For example, if someone has encountered a toxic drug supply, or lost access to their drug of choice, or is in need of a detox bed, their ability to attend and complete their work is hindered. Workplaces that engage in harm reduction work do not account for these gaps in scheduling. Despite the institutional emphasis on hiring people with lived experience of drug use – it looks good for organizations that offer health services to claim they are employing people with this lived experience – these employers don’t offer, nor do their unions advocate for, positions that accommodate the lived realities of people actively using drugs.

Harm reduction work requires flexibility. Front line workers are doing grueling work that comes with immense trauma and grief that can linger over their lifetimes. According to previous Briarpatch reporting by Mick Sweetman, “A study sponsored by the Calgary Homeless Foundation and published by professors at the University of Calgary and Athabasca University showed that 36 per cent of front-line workers [in Calgary] reported symptoms of PTSD.” Mskwaasin Agnew, Anishinaabemowin for Redstone, a Cree and Dene and a band member of Salt River First Nation and a harm reduction worker at Toronto Indigenous Harm Reduction agrees. “[Peer workers] are doing grueling front line work. It's not easy, and there's no support for grief. There's no support for the trauma that they’re watching. There’s absolutely ways to accommodate people - you have to be better at scheduling your workers and have relief staff.”

On January 7, 2015, a THRWU member named S. was terminated from her job without cause two days before her six-month probationary period was to conclude, according to a blog post from the union. In the post, THRWU detailed the following: Within the agency at which she worked, S. had advocated for better treatment of workers. The employer offered S. two weeks of severance pay, in exchange for silence on the matter but S. refused to sign the document obliging her to silence. She shared her grievances with THRWU which then coordinated a direct action to approach the executive director and demand that S. be given her termination pay, with no requirement for non-disclosure. About 25 THRWU members flooded the lobby of the agency and supported S. in reading her demands to the executive director. S. ultimately got one week’s termination pay, with no requirement to remain silent.

A former THRWU member who participated in the action recalled, “When people are isolated [in] pushing harm reduction in some of these organizations, feeling like they were part of this bigger movement […] was really empowering.”

There were also other material wins such as demanding that peer workers be able to access keys to the building as a symbolic and simultaneously pragmatic gesture that informs workers they are in control of their own work. When they can go where they want and do what they want without having to seek permission, it is a form of empowerment. Members who were a part of this string of wins were left feeling the momentum of the organizing.

When workers die

Despite these victories, when the overdose crisis reached a pivotal point in 2017, members could no longer sustain union activity, particularly after a number had passed away from the toxic drug supply. Their passings were among the 53,821 toxic supply deaths recorded nationally from 2016 to March 2025, as well as the 868 deaths in Ontario in 2016 and 1,270 in 2017. THRWU stopped operating in 2017. Members were forced to deprioritize their rights as workers to address the toxic drug supply crisis on the ground, with some members transitioning to volunteer alongside the Toronto Overdose Prevention Society to create the Moss Park Overdose Prevention Site.

Zoë Dodd, a Toronto harm reduction worker and a founding member of THRWU recounts, “We had a lot of workers lose their jobs. We could have had more union support when harm reduction was under attack – it was a labour issue.”

In 2024, Ontario recorded 2,231 deaths from the toxic drug supply crisis. Instead of compassionately addressing this crisis, on December 4, 2024, Ontario adopted Bill 223, which prohibits 10 supervised consumption sites from distributing clean needles, offering supervised consumption, or providing a safe drug supply. Ontario put into effect an alternative funding program – an abstinence-based model called homelessness and addiction recovery treatment [HART] Hub, with zero support for those who need drug consumption services.

In June 2025, the Ontario government enacted Bill 6, the Safer Municipalities Act, which creates additional pathways to criminalize individuals experiencing homelessness and using drugs. In Saskatchewan, the Safe Spaces Act came into effect on August 1, 2025 and lets municipalities opt-in to give police the power to seize "street weapons" which include hypodermic needles, as well as arrest anyone in possession of them. In April 2024, British Columbia recriminalized the use of drugs in public spaces, also claiming it was to address public safety concerns. These measures do not truly address issues of safety, but rather, are a means of criminalizing those who don’t have the means to use drugs in private.

As the crisis continues, labour rights are relegated to the back burner as community members and workers become casualties to these intersecting crises created and exacerbated by policy decisions. Zoë Dodd, a Toronto harm reduction worker and a founding member of THRWU recounts, “We had a lot of workers lose their jobs. We could have had more union support when harm reduction was under attack – it was a labour issue. We've been losing so much of our work. We've lost a lot of workforce to overdose and grief and loss and mental health challenges. And then on top of it, we lost a workforce to the closure of the sites.”

THRWU’s story is a testament to labour organizing and simultaneously a lesson about what does and doesn’t work. Though the union may have folded, it’s a marker of the possibilities of organizing: how workers can dream beyond institutional unions, create organizing rooted in direct action, empower workers, and promote harm reduction to sustain life.

Immortalized on his personal website, Balian’s words read, “My stories are one of survival under a state of constant, relentless, corrupt[ion] and an insidious war waged on me and my friends.” Eight years after his passing, his words ring truer than ever. We must remember that harm reduction organizing and labour organizing are threads of the same cloth, and we must build a vibrant solidarity between both.