While not often acknowledged by union activists, the labour movement is dangerously close to being an obsolete, even counterproductive vehicle for transformative social change. In many ways, it is the victim of its own success – success in the sense that an established, privileged legal framework for unions now exists, virtually eliminating the possibility that union leaders will fight for much more than security for their memberships. Labour leadership now tends to make appeals to the powerful, particularly the Canadian federal and provincial governments, rather than building worker power from below. But no ruling government of Canada will end precarious work, shut down parasitical corporations, or address some of the fundamental underpinnings of the Canadian state – like the fact that the land we all work on has been illegally expropriated from Indigenous peoples, who continue to be harmed by the same industries that create the conditions for a comfortable, unionized middle class.

We want to share our vision for a radically different labour movement, a vision that is influenced by our experiences as young women workers active in our union at both local and national levels. But we are also informed by our education on the streets of Montreal, our solidarity work with grassroots organizations, and our anarchist politics. In much of the union world, union work exists separately from “other activism.” We envision a future that brings these together to create a powerful and effective political left.

One cannot live by labour alone

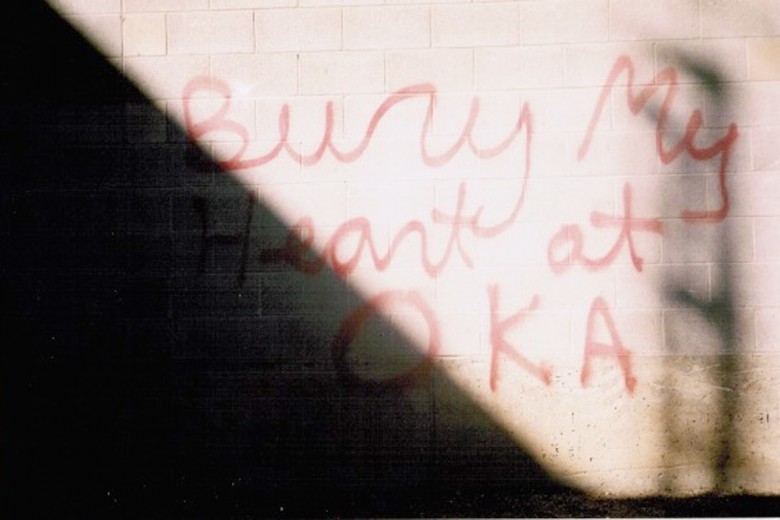

Molly: During the 2012 Quebec student strike, there were rallying cries for “la grève générale illimitée” (unlimited general strike) and “la grève sociale” (social strike). Striking students looked to our fellow workers to join us in refusing the Quebec Liberal Party’s cuts to our welfare, services, and working conditions. Union support – in the form of solidarity strikes and direct action – would have been instrumental in expanding the printemps érable (Maple Spring) into a true social strike, and students were ready to stand in solidarity and join our struggles.

But we were disappointed. At their best, unions supported the movement from the sidelines by writing cheques, but at worst leadership actively discouraged solidarity between students and workers – such as when Michel Arsenault and Ken Georgetti (then presidents of the Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Québec and the Canadian Labour Congress, respectively) agreed to discourage donations from their locals to the striking student coalitions. The unionized workers of the Société de Transport de Montréal (STM) drove buses in which hundreds of kettled protesters were corralled, sometimes for several or more hours at a time without food or water, while awaiting processing under the repressive anti-protest bylaw P-6. And one year later, the Montreal police, supposedly workers “just like us,” appropriated our tactics and imagery by staging confrontational street demonstrations and wearing huge red squares to support their own contract negotiations. Unions actively distanced themselves from one of the most promising social movements of the decade while continuing to support and represent people who brutally repressed it.

The student strike wasn’t only a movement that aligned ideologically with the labour-left, but one that had explicitly pro-worker goals. Quebec students were fighting for a society with less debt, better public services, and more accessible education; these are material advantages for working families and promote a social context where unions can be stronger. But the tactics of the strike, it seemed, were so foreign to unions that they didn’t want much to do with them – and we include in that the tactic of the strike itself, which never had full, vocal support from union leadership.

The strike strategy employed by students in the winter and spring of 2012 included not only hard picketing of university and classroom spaces, but picketing the city itself, through “manif-actions” against sites of capital, such as banks and the stock market, and through mass demonstrations and street battles that overwhelmed city infrastructure and police. The labour movement did not support the tactics that had once made it strong: direct action, confrontation, and strikes. Instead, union leadership used its influence to pressure student leaders to make a weak deal with the government at the negotiating table, with Michel Arsenault stating that “at the moment, the best approach [for organized labour] is to facilitate a settlement instead of fueling the fires.”

This self-isolation of labour unions from other struggles is a major barrier to labour’s own success as a movement. Aside from losing out on incredible opportunities to grow a strong and dynamic left, the unquestioning perception within unions that unions are a benevolent force in society prevents many unionists from critically engaging with organized labour’s repressive tendencies.

There is no recognition within the labour movement of the role that unions and some workers have played in the ongoing disenfranchisement and impoverishment of Indigenous peoples, the marginalization of racialized migrants, the ongoing criminalization of sex workers, the incarceration of poor people, or the stifling of radical grassroots movements – the Quebec student strike being only one of many examples. By situating unions uncritically as a positive force for all workers – and, indeed, all of society – we run the risk of excluding the many people who, whether historically or by the nature of their work, are not supported or protected by union structures. And we too quickly forget the times that labour leaders and privileged union members have actively supported a return to social peace at the expense of powerful social movements.

Beyond electoral politics

Amber: Six months ago, I attended a leadership class organized by our national union. On the last day, the current regional vice-presidents came to Toronto for a leadership Q-and-A. Most of the questions were along the lines of “How do we stop Harper?” Legitimate questions, but ones I felt didn’t touch on any fundamental issues. Pushing a little bit further, I asked them to put aside the immediate political context and instead describe their vision of a strong labour movement with the capacity to achieve all of its goals. What are those goals? What would that society look like? What are we actually fighting for? Surely, it’s not just “stop Harper”?

My trust in the vision of my national leadership quickly eroded as the NDP platform was repeated back word-for-word: “$15-a-day child care,” “pay equality,” “protecting the middle class.” Their answers were so unimaginative that I was left thinking they actually had no long-term, transformative vision of what they wanted the labour movement to achieve beyond helping elect an NDP government.

How did it get this way? Unions are now so detached from grassroots struggles that the only political terrain we engage with is electoral politics. Instead of providing our members with a strong political education about labour and its history of struggle and resistance, unions tell their members to go vote and to leave the big decisions for top leadership. A recent example is how the $5 million emergency budget for the “Vote to Stop the Cuts” campaign approved by the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC) national convention was unilaterally allocated toward advertising campaigns and a leadership tour. These are political strategies that err entirely on the side of caution, of maintaining the status quo, and of achieving only piecemeal gains instead of radically challenging the systemic problems faced by workers, especially vulnerable, non-unionized workers.

This is a huge problem, and one that in many ways stems from the reality that the majority of unionized workers in Canada are members of the middle class. Canadian unions now exist – proudly and explicitly – to protect and maintain a membership with well-paid, middle-class jobs. Some aspects of this are great; we want people to have the ability to support their families in a dignified way. But the existence of a middle class is predicated on a national and international lower class that bears the brunt of predatory capitalism so that the middle class does not have to do so.

Unions have played a part in generating and maintaining an exploitable underclass of non-unionized, poor, and non-recognized workers, and they certainly haven’t worked hard to end this class structure. Capitalism continues to chew through the poorest and most marginalized of us, to whom unions devote few resources. Instead of organizing the poor and precarious workers who feel the full force of capitalist violence, unionized workers have clung more tightly to their own protections while they are slowly and steadily starved of social and political power by austerity.

Our vision

Unions need to radically reassess our shared work and goals. At best, our union leadership doesn’t even know where they want the labour movement to go. At worst, their goals align with those of the most powerful members of the corporate and political realms through the benefits afforded to them as part of an especially privileged section of middle-class workers. In our view, unions are becoming an obstacle to working class liberation.

We need to recognize that our unions cannot be allies of the progressive or radical left – nor of Indigenous people, migrants, queer and trans people, sex workers or people of colour – when we represent the police, border guards, and prison guards. The interests of the latter groups in the administration and criminalization of marginalized populations are irreconcilable with the liberatory and protective capacities of unions, and, if our unions represent the latter instead of the former, we have unequivocally chosen the wrong side. This was extremely clear to us at the most recent PSAC national convention, when delegates voted to provide legal support to members who fire a gun at work, on the very same day that riots were exploding in Baltimore over the murder of Freddie Gray by the Baltimore police. We must take up the call initiated by United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America (UAW) 2865 in California to demand the complete disaffiliation of all police, prison, and border guards from our unions.

We need to engage our members in real political action and direct democracy. Our members need space to develop a political analysis that comes out of their experience as workers, which means providing them with an intersectional understanding of historical and contemporary labour struggles, and prioritizing member participation in all levels of union decision-making. As our experiences in the student strikes have shown, direct democratic participation radicalizes and empowers people, and promotes large-scale mobilization, a strong sense of solidarity, and creative resistance strategies. Unions can and should restructure our systems of governance to reflect a more directly democratic model.

One example of such a model is CLASSE (Coalition large de l’Association pour une solidarité syndicale étudiante), which was the largest coalition of striking students in Quebec in 2012 and 2015. There are two aspects of CLASSE on which we want to focus.

First, CLASSE was a form of direct rather than representative democracy – all actors within CLASSE, including its executive leadership, were bound by the decisions made in grassroots student assemblies. These directives were examined, debated, and renewed by students across Quebec every week, contributing to student engagement and the strength of the strike. This democratic accountability was taken extremely seriously. For example, in spring 2015, the executive proposed a “strategic retreat” without a mandate from their membership. CLASSE’s member associations not only immediately cried foul, but refused to accept the executive’s resignation in order to publicly boot them out of the organization.

Second, CLASSE supported and encouraged alternative pressure tactics beyond the strike. Members participated in direct action, property destruction, and street fights with the police. CLASSE never denounced or isolated any of its members for these actions; instead, it set up a legal fund and forewent a politics of respectability for a politics of solidarity and support.

Unions must reject our current role as government lobbyists in favour of directly confronting the systemic forces of capitalism. We need to cease being brokers of conflict resolution between workers and bosses, and instead face our role in maintaining the colonial economy. Union leadership should seek and actively develop a membership that is mobilized, engaged, and an actual threat to the maintenance of social peace under the capitalist settler state. Union members should be fighting daily in solidarity with workers who do not have the same protections, and fighting hard!

We need to push our unions in a new direction: closer to the grassroots struggles from which we have been distant for so long. We must centre progressive social movements of all kinds as part and parcel of the labour struggle. We need to start directly supporting workers in the most precarious industries, and invite their voices into our locals, committees, and conventions. To accomplish real and lasting solidarity, we need to do more than simply create space for vulnerable workers as part of our latest “social justice initiative” or as an additional equity group. We as union members and middle-class workers must be ready to relinquish the control and leadership of the labour movement and to mobilize our human, financial, and structural resources in the service of the most disenfranchised. We must place our trust in powerful, confrontational social movements comprised of unionized and non-unionized workers – not future governments.

Finally, unions should strive toward organizing ourselves out of existence, as our ultimate goal needs to be the destruction of the very things that are currently fundamental to unions’ survival: labour, as it exists under capitalism; the colonial economy; social hierarchies; and capitalism itself. In a society in which unions have been profoundly stagnant and deeply unimaginative for so long, it is time to dream and act to create a labour movement that is unapologetic in its goal of liberation: a workers’ movement that doesn’t simply represent, but empowers.