“How to work a four-hour week and join the new rich.” Such is the promise of Tim Ferriss, one of the sweethearts of corporate America. His time-crunching productivity theory is just one among dozens of other “work smart, not hard” arguments. But another, anticapitalist line of argument for a reduced work week exists. As global temperatures climb to an all-time high and the average standard of living creeps sluggishly upward despite technological advancements that promised a sharp increase, some voices in the U.K. are calling for a reduction in work hours as one of the pillars of a Green New Deal. It’s time for activists in Canada to pick up that advocacy.

A reduced work week without salary cuts would be one among many steps to rebuild an economy based not on the pursuit of growth but of sufficiency.

Advocates for a Green New Deal that includes a reduced work week are looking to challenge the assumption that growth is always good. A reduced work week without salary cuts would be one among many steps to rebuild an economy based not on the pursuit of growth but of sufficiency.

Rethinking unemployment

In 1930, economist John Maynard Keynes imagined that his grandchildren might live in “an age of leisure and abundance” in which we might return to the noble principle that “the love of money is detestable.” By all measures, this age of abundance should be possible today: we are, after all, producing more than ever. Yet 4.2 billion people – over half of the world’s total population – live in poverty and that number has been increasing since 1981. We have more homes without people than people without homes, but foreclosure is profitable; we throw out one third of the food we produce globally while at least one third of the global population lives in hunger.

Given that most people are barely scraping by while working 40 hours a week, it is no surprise that the idea of working less is terrifying. In reducing the amount of labour necessary for production, job automation – the very process which, for Keynes, made a leisure society possible – means work is increasingly seen as a privilege, while unemployment (which could be leisure) is equivalent to poverty.

We throw out one third of the food we produce globally while at least one third of the global population lives in hunger.

The utopian – yet widespread – prediction that technology would make human life easier has materialized for very few; certainly not for workers, whose work conditions have been steadily worsening in recent years.

The argument for a reduced work week asks: why do we work to produce so much more than we can possibly use? Why not work less, waste less, distribute better, and enjoy the age of abundance that we’ve been promised?

How much do we even need to work?

The argument at hand is not just that abandoning the 40-hour work week is possible – it is that it is necessary for the survival of the planet. “The move towards a shorter-working week,” declared U.K.-based think tank Autonomy, “would go some way to helping transition from a materialistic consumer culture which is damaging for both wellbeing and the environment.”

Most calls for a reduced work week, based on a case study in New Zealand, ask for a four-day work week. But others, like Autonomy’s, call for something much more radical: A nine-hour work week, or just over one full day. They say it’s what’s needed to avoid more than 2C of heating in the U.K., at current carbon intensity levels.

It would be a world where more things are made with what’s available, for the simple reason that humans love making things.

More leisure time, on its own, would change our commuting and consumption habits and drastically reduce carbon emissions: Autonomy predicts that a 25 per cent reduction in working hours could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 20 per cent and our ecological footprint by just over 30 per cent. We’d commute less, and our commutes would be less of a rush; we’d use more public transportation and fewer cars. It would decimate a few industries (like take-out food and online delivery) that we use mostly because we’re short on time – and with them all their ancillary industries, like throwaway plastic packaging, which makes up 40 per cent of the demand for plastic. Our mental and physical health would improve, Autonomy argues, which would in turn reduce the heavy load that health care workers shoulder.

Leisure time could be filled not by frantic consumption but by relaxed hobbies and artisanship. It would be a world with more home-cooked meals; food grown and harvested in community gardens; clothes, furniture, and electronics that are mended, not replaced; and more things made with what’s available, for the simple reason that humans love making things. This new style of production could also shift our consumption patterns toward local products, which could substantially cut our dependence on freight transport – which, as of 2015, was responsible for 30 per cent of transport-related CO2 emissions, or 7 per cent of total emissions, and has only been increasing since then.

Degrowth for a Red Deal

One of founding principles of the Red Deal – a complement to the Green New Deal, focused on Indigenous sovereignty – is divestment from not just fossil fuels, but also prisons, the military, and the detention industry. “Imagine if the U.S. military had to hold a bake sale to keep its doors open instead of preschools, domestic violence shelters, art and language programs, and family planning clinics?” asks the Red Nation, the Indigenous-led activist group responsible for the Red Deal. “With the resources we gain from divestment, we could end world hunger, illiteracy, child hunger, homelessness, and build renewable energy tomorrow.”

In Jacobin, Nick Estes, co-founder of the Red Nation, elaborates: “Each [Indigenous-led climate] movement rises against colonial and corporate extractive projects. But what’s often downplayed is the revolutionary potency of what Indigenous resistance stands for: caretaking and creating just relations between human and nonhuman worlds on a planet thoroughly devastated by capitalism.”

By denying the necessity of that greed in the first place, degrowth questions one of the core motivations for colonialism and imperialism.

These arguments are familiar to those who have followed the increasing popularity of degrowth, an economic theory which has structured many of the discussions around a Green New Deal. Degrowth is a powerful ally to the idea of decolonization: Both at home and abroad, colonialism and imperialism have been justified by colonizers’ greed for raw natural resources and cheap or slave labour. By denying the necessity of that greed in the first place, degrowth questions one of the core motivations for colonialism and imperialism.

The Canadian government is heavily influenced by the interests of those who profit from resource extraction. As a result, the government has legalized the dispossession of Indigenous people of their lands, in order to more efficiently drill, dig, log, and siphon natural resources from that land; in the instances when this process isn’t legal, the laws are ignored. As a result, Indigenous communities continue to see their water poisoned, treaties broken, land protectors jailed, and their children stolen.

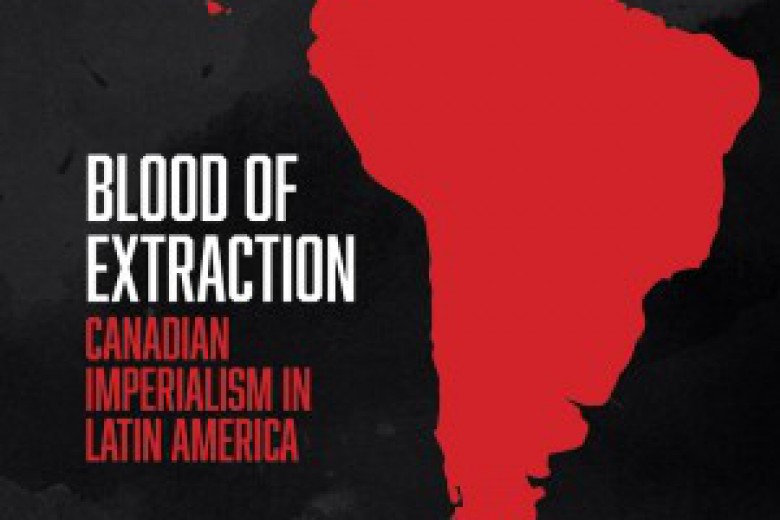

What Canadian companies do at home, they do abroad too. The Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) and the TSX Venture Exchange host almost 50 per cent of the world’s public mining companies, trading over $189 billion in mining equity. Canadian companies use obscure international trade mechanisms to suppress local governments and, where that fails, simply kill locals who might inconvenience the production process.

With exploitation at the heart of colonialism, any anti-colonial project must fight overproduction, and any anti-extraction project must fight for the sovereignty of Indigenous people across the world.

Utopia may be simple, but not easy

Critics of reduced work week utopianism make some salient points. The reduced work week on its own creates conditions that, historically, have enabled rampant consumerism: More people with more time and more money. We might just be trading desk ellipticals for more video games. Like a universal basic income, it might cause a wage-price spiral: If people can afford more, why not simply raise the rent?

Eliminating all unnecessary production is a deeply radical idea, and must be accompanied by a revision of the purpose of work on a global scale.

Those are good questions. They also lack ambition. Eliminating all unnecessary production is a deeply radical idea, and must be accompanied by a revision of the purpose of work on a global scale. It must interrogate the notion at the center of capitalism that profit margins must grow. But that interrogation won’t happen without the support of other policies that restructure our economy. We’d need a tax on unsold goods to eliminate unnecessary production. We’d need a maximum wage ratio policy, to free up capital to pay workers. We’d need to close loopholes that allow tax evasion, and to allocate that tax money more effectively: to green housing, for instance. If we’re aiming for an end to imperialism, even those things are not sufficient: A robust framework for international trade law would have to rid us of transfer mispricing and other fiscal fraud tactics that have allowed companies in the Global North to extort the Global South.

This conversation hasn’t really been on the table in Canada. But its undercurrents are already here: Both The Leap’s Green New Deal and the NDP’s New Deal for People call for decent work. An anti-imperial, environmentalist reduced workweek movement goes further: It presents the fight against climate change and the struggle for labour rights as one and the same. If we are to grow a resistance, a united movement that threatens the larger-than-life economic laws we live under, reduced work week advocacy gives us nothing less than an argument that reconciles all the causes we are fighting for.