Feeding My Family is a grassroots group that formed in Nunavut in 2012. From Labrador to Alaska, the group has since provided a forum where northerners can come together despite the distances that separate their communities. The Feeding My Family Facebook group works to raise awareness of how the high cost of food has been impacting northern communities and to encourage action from both northerners and southerners.

Introductions

Israel Mablick: I was born in Frobisher Bay, Northwest Territories, now known as Iqaluit, Nunavut, and was raised in Pond Inlet, Nunavut. My mother was a teacher and when I was very young I remember we went to Montreal for a couple of summers. As a boy, this was confusing and a cultural shock. Our family moved to Ottawa, Yellowknife, Cambridge Bay, and back to Iqaluit when my parents divorced. I have lived and worked throughout Nunavut, in Igloolik, Iqaluit, and Pond Inlet. In 2011, my family and I moved back to Iqaluit, and we have been here since, raising our five wonderful children. We live together with my mother, sister, nephew, and younger brother in a two-bedroom unit, while I work as a security guard.

Leesee Papatsie: I was born in Pangnirtung, Nunavut. We moved to Iqaluit (the capital) when I was young. My parents only spoke Inuktitut and that is my first language. I have two sisters and four brothers. I grew up eating country food, like seal, caribou, fish, polar bear, and beluga whale. We can eat these raw, cooked, frozen, or dried. There were times when we were hungry growing up; not starving, but hungry. We would have nothing to eat but tea and bannock. I remember when I was a kid, I stole food from the store; that pear tasted so good. Currently, I work for the government of Nunavut in the Parks and Special Places division.

Jannie Wing-Sea Leung: I am a community organizer and health worker currently based in Coast Salish Territories (Vancouver). I first became involved with Feeding My Family while living in Iqaluit and continue to support community actions for food justice in the North.

Why did communities organize the food protests in 2011? How did you get involved?

Leesee: They organized the protests to raise awareness of the high cost of food in the North and to ask stores not to sell rotten food. There was a guy in Coral Harbour who mentioned on Facebook one Saturday morning that he was tired of the stores selling rotten foods at high prices. And then there were words about starting a protest and a guy saying I’m going to stand in front of NorthMart (the local grocery store). Community members gathered outside the store and did their first protest to come together as one, to protest the high cost of food. Then there was another protest.

I know in the North, due to isolation and the extremely high cost of travel between communities, northerners use Facebook to connect to their relatives and friends. We created a Facebook group to ask community members to stand together.

Israel: Communities gathered to protest because they also got tired of companies like the North West Company and Arctic Co-operatives Limited price gouging for far too long. They wanted to help others who struggle on a daily basis; they wanted to make a difference.

I saw one person protesting, and it started me thinking. Like him, I too struggle, and I know of others who struggle more, so I decided to take action, too. To stand up where others can’t. I joined Feeding My Family to fight against price gouging, so we Nunavummiut can be and feel part of this country of ours.

Jannie: I got involved two years ago when I was living in Iqaluit. There was a lot of attention and momentum around the food protests and the pictures of the food prices being posted on the Facebook page. I was lucky that I had a steady job and was able to pay these prices, but this made it all the more important that I support these actions and my community. Even though I’m not currently living in the North, I continue to support and be involved with Feeding My Family.

What changes have you seen since the first protests in 2011?

Leesee: I’ve seen northerners speak out more on different issues, such as the actions against seismic testing in Clyde River. A lot more people are noticing the food prices and the “best before” dates on foods. We’ve been encouraging people to take pictures of food prices in their community stores to let others know. We’ve been encouraging northerners to go out and say this is wrong. There has been a lot of media coverage of the protests and the boycott organized by Feeding My Family, and a lot more support online. For the Inuit, right at the beginning it was hard, because it has not been in the Inuit tradition to protest.

Talking about food hunger in the North does not seem so “wrong” anymore. There is a lot more understanding of the northerners’ situation, how food insecurity is a complex issue. Other parts of the North have been posting pictures of food prices on the site as well. There is more interest and more understanding not just in Canada but all over the world.

There has been a lot of interest on the political level as well. Feeding My Family has been mentioned numerous times in the Nunavut legislature and in Parliament. The Nunavut government’s Food Security Strategy and Action Plan came out in May 2014 (they had been working on the plan since the creation of Nunavut). Now the Nunavut Food Security Coalition has been having regular meetings to work on this plan.

Israel: People outside of Nunavut are now more educated about the daily struggles we face as Nunavummiut, with the price gouging and suffering. Our voices have been heard. This is just the beginning and we could go further but we need to know what our next steps are. Because we live all over the place, it makes it hard to organize.

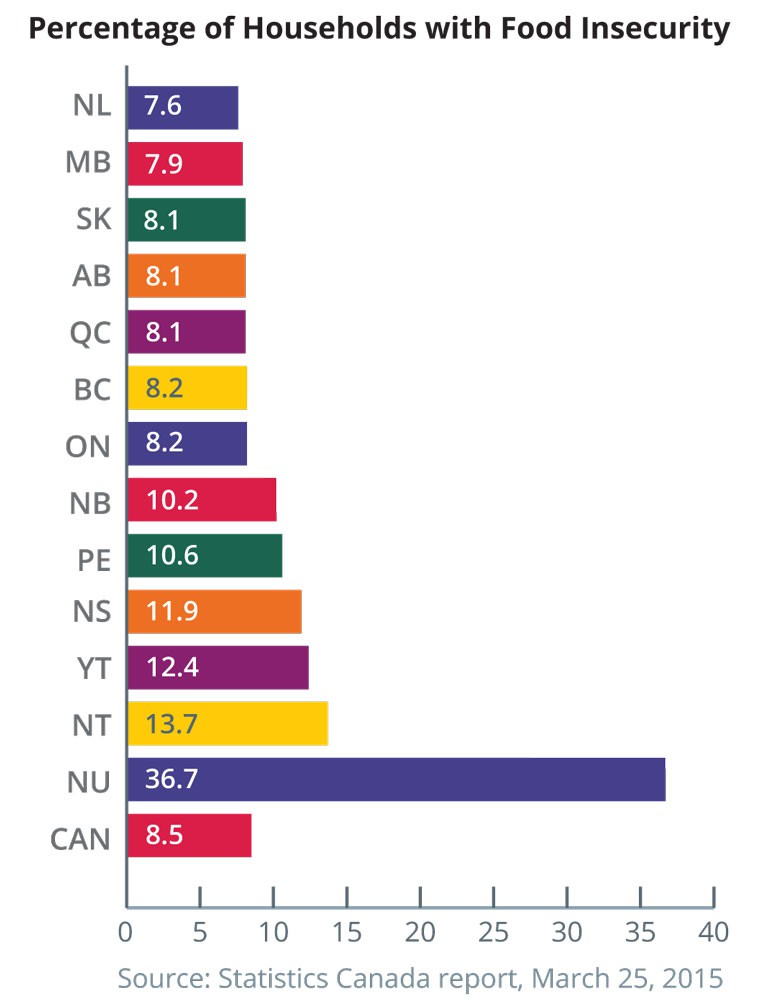

FOOD INSECURITY IN CANADAAccording to the Statistics Canada definition, food insecurity exists within a household when one or more members do not have access to the variety or quantity of food that they need due to lack of money.

Nearly 37 per cent of households in Nunavut lack sufficient access to safe and healthy food – a level that is four times the national average.

Among the provinces, the Maritimes has the worst food security.

In 2011–2012, the rate of food insecurity in Canada was more than three times higher in households where government benefits were the main source of income (21.4 per cent) compared with households with an alternate main source of income (6.1 per cent).

Among various household types, lone-parent families with children under 18 reported the highest rate of household food insecurity, at 22.6 per cent.

What challenges has Feeding My Family faced?

Leesee: The biggest challenge I found with Feeding My Family is that some people deny that there’s hunger. Sometimes there are negative responses online. People who did not go hungry growing up have a harder time understanding. But hunger is still very much there; there are still people who have not eaten today.

When Feeding My Family first started, it started to go in different directions, and it was good that we were able to stay focused on this. Some want to direct our attention to the airlines, to the governments and the Inuit organizations, and we understand that. But Feeding My Family is about the high cost of food. If another person or group would like to take a different direction, they can take the lead on it. What we have started is just part of the story.

Now that the Facebook group has grown to over 24,000 members, one challenge is how to keep the focus on northerners and Inuit. A lot of people have started their own groups now, for their own communities or focusing on a specific topic. It’s really encouraging to see people organizing in this way.

What have been the effects of documenting food prices on Facebook and the other community actions?

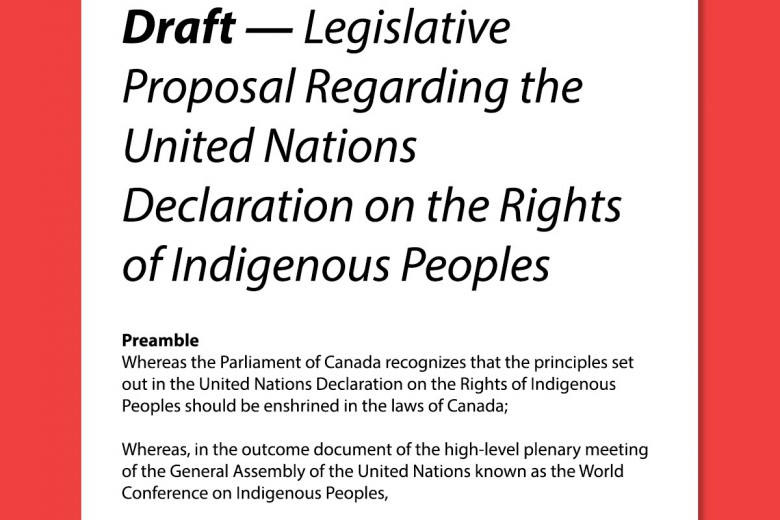

Leesee: I think it’s had a lot of impact on the federal Nutrition North program that subsidizes northern retailers for the shipping costs of healthy foods. The program says the subsidy will trickle down to customers, but northerners have been saying all along that it has not been lowering prices. There was an outcry and the politicians listened. The public did that. Members of the Nunavut legislative assembly, as well as those of the Northwest Territories and Yukon, requested the auditor general of Canada audit the Nutrition North program. In the fall of 2014, the auditor general released its report, where it could not verify whether northern retailers were passing on the savings to customers.

Jannie: The auditor general’s report really validated what communities have been saying all along, and the pictures were proof. It makes a strong point that community voices need to be listened to, that they’re telling us how these policies actually look on the ground and what’s not working.

Food prices in Nunavut are 140 per cent higher than the rest of Canada and at the same time, the two main stores that operate in northern communities make big profits. What do you think needs to change for food to be a right and not a profit-making venture in the North?

Leesee: I think not enough northerners or Inuit seem to understand it’s a basic human right that we have in Canada. And the stores could definitely lower their food prices. There’s no easy answer for how to do that. It could be lowering freight costs, more subsidies from different levels of government and even Inuit organizations, and people finding ways to be self-reliant.

Israel: I understand that businesses have to make money as well but it is just way too much. They really are gouging. The annual income of North West Company’s CEO is $2 million. My annual income for 2014 is $36,000 and I have five kids and a wife, and we have survived. The CEO lives in southern Canada where prices are cheap. I am sure he doesn’t need all that money.

People are coming together to fight our government and voice our concerns. Government has always and will always want us to listen to their reasons, but it is now time for them to listen to us.

Jannie: These community actions pressure governments to be accountable and transparent in how public funds are being used, to protect people’s right to food, and to enforce food safety regulations. There have been discussions as well about the need for more hunter support programs and community freezers. Although most families need to buy food at the grocery stores now, a lot of people still hunt for sustenance, and food sharing networks are very strong. There are some amazing initiatives being started up by northerners like country food markets or programs bringing youth out on the land to hunt.

Colonization is a major cause of the current food crisis in Nunavut, with Inuit being relocated into permanent settlements, sled dogs being killed by the RCMP, and residential schools, which disrupted intergenerational knowledge of hunting and living off the land. How do you see Feeding My Family as connected to other Indigenous movements? What role do non-Indigenous people have?

Leesee: They are very much connected, very much so. As Aboriginals, we are treated as less by the federal government. But now Aboriginals are speaking out more. There is a lot more awareness about other Aboriginal groups across the country. The federal government had assimilated First Nations across the country, and it is a very similar situation in the North.

For non-Indigenous people, there is a big role, a huge role. Because they can write to their members of Parliament, they can spread awareness, they can send donations, sign petitions.

Jannie: As someone who is not Indigenous, I think it’s crucial for us to work in solidarity with actions that are being led by Inuit and other Indigenous peoples. This is not just an Inuit or northern issue; we all have a role in taking action against it.

Looking back since 2011 and 2012, what lessons can you draw from your experiences with Feeding My Family?

Leesee: I’ve learned that if the government is willing to do something, they can do it, any kind of government. Look at the government of Nunavut, and how fast they got their Nunavut food coalition strategy coming out. I’ve also learned that there are people out there who are hungry every day. I knew that before, but really knowing how much hunger is out there is different. And I’ve learned that people care when someone’s hungry. It’s amazing how much people care.

The most important part is speaking when you believe in something, and sticking to it. And staying focused. With so many different issues we face in the North, so many other factors to consider, the big thing I’ve learned is staying focused. Also learning about yourself and taking risks, not knowing if it’s going to work or not. Doing something you believe in can be risky.