Whenever a job posting goes up at Briarpatch, prospective applicants in places like Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver have a common concern: do you have to move to southern Saskatchewan for the job? I got the same answer that everyone gets to this question: yes, you do, but it’s honestly not such a bad place. And it’s true: the land of living skies is far greater than many know.

Stressing the importance of community and history is commonplace on the left, but putting the two together to forge historical communities of struggle – grounded in a place – is an uphill battle in a world of commuters and itinerant students, of contract work and urban sprawl. Successful organizing ultimately comes down to building relationships, and the merits of growing where you were planted, rather than heading to where the perceived action is, shouldn’t be discounted.

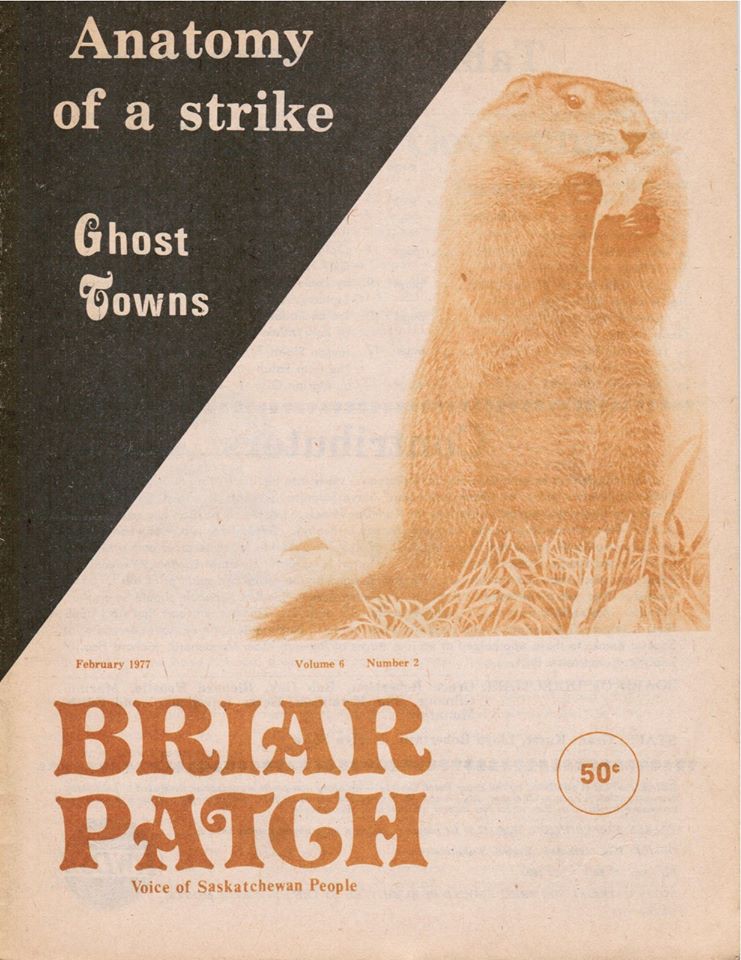

Briarpatch will never be published from anywhere but Saskatchewan because its infrastructure is rooted in this place, this land, and these people. Its roots – that radical groundwork – is why it still exists at all. The community of activists that has fought to sustain the magazine spans generations, with a legacy that runs from the militancy of the ’70s (when the left was a major force) to today, when we often struggle merely to prevent further erosion of past gains. Former editor Clare Powell hasn’t been on the payroll since Iron Maiden released their debut album, but every month Clare joins us in the basement to stuff envelopes for our renewal notices. Clare turned 80 this summer and he is just one of many models here, in southern Saskatchewan, of what it means to make a life on the left.

Publications like Briarpatch form part of what Alan Sears calls our infrastructure of dissent, which Sears defines as “the range of formal and informal organizations through which we develop our capacities to analyze (mapping the system), communicate (through official and alternative media channels), and take strategic action in real solidarity.”

“As ways of life and work change,” Sears notes, “the infrastructure of dissent that thrived in one set of conditions can wither.” What’s more, while activists in the ’70s were spurred by the unprecedented mass movements and radical politics of the late ’60s, many activists today have no memory of, or connection to, a vibrant political left: a left with audacity, vision, and the capacity for major advances. Millennials and Gen Xers were born into a world of cutbacks, privatization, and free market ideology, a world in which the left has always been in retreat and disarray.

This might seem a strange context in which to introduce a new layout and design for Briarpatch, but here’s the connection: the scaffolding that got us to this place has been erected over time by a community rooted in place and committed to a project no matter the odds. The magazine is able to serve as a truly national platform for independent reporting and serious analysis only because local relationships – an infrastructure of care and commitment – hold things together.

One of the most special things to me about Briarpatch is its longstanding anti-colonial mandate – a commitment to amplifying and supporting Indigenous struggles that goes back to Briarpatch’s earliest days in the ’70s when the collective worked closely with New Breed magazine. New Breed was published by the Métis Nation–Saskatchewan and was an integral piece of the militant, critical infrastructure of the Métis resurgence. The relationships between Briarpatch and New Breed were rooted in place and built over time.

Part of the lesson in this, at least for me, is that meaningful solidarity is much more than showing up at an event. Solidarity means having capacity and resources to offer to people who are engaged in struggle. Without infrastructure, our solidarity is fleeting and frequently tokenistic or self-serving. But when we have independent, grassroots infrastructure and resources – be it a nationally distributed magazine, an email list, or a cargo van with a full tank of gas – our solidarity is material rather than symbolic.

This issue of the ’patch is dedicated to everyone who helped get us here, with special thanks to a couple people in particular. First, thanks to former editor/publisher Valerie Zink who did all the initial legwork to get us publishing in colour and to set about the redesign. Second, thanks to Winnipeg-based designer Mike Carroll, whose spirit of enthusiasm, collaboration, and patience was the perfect match for us. We hope readers like the results.