It is illusory to imagine that corporations will ever be entirely transparent or accountable, despite their virtuous claims to social responsibility and sustainability. However this does not mean that resistance is futile.

– Stuart Kirsch, Mining Capitalism: The Relationship between Corporations and Their Critics.

Circa 2002, in a town nestled in the lush northern coffee-growing highlands of Nicaragua, Padre Teodoro detected the stealthy presence of a Canadian geologist hauling rocks in a backpack. On alert, he began to mobilize the children in his catechism class against mining. Local parishioners thought that he was a bit loquito. Crazy he was not, though, and most people in the municipality of Rancho Grande now hail him and his successors, Padre Marlon and Padre Pablo, as local heroes in their 14-year anti-mining struggle.

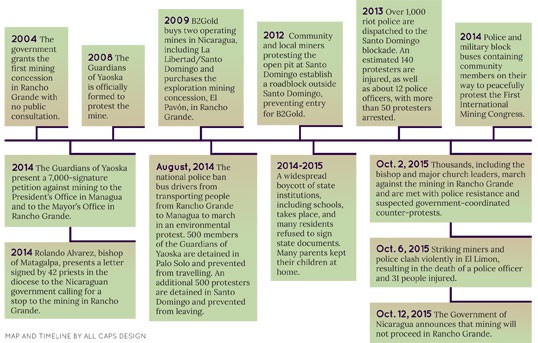

The story of Rancho Grande’s conflict with Nicaragua’s largest gold mining investor and exporter, Vancouver-based B2Gold, is a case study in the relationships between Canadian mining companies and agricultural communities in Latin America. Rancho Grande is not a mining community, but an agricultural one that just happens to be sitting on subsurface reserves of gold. As elsewhere in the world, in Rancho Grande, farmers (campesinos) have had to become land defenders (guardianes), fighting politicians and companies that propose mining as the only option for rural development. And as with the 214 Latin American communities currently embroiled in conflict, as documented by the region’s Mining Conflicts Observatory (OCMAL), Rancho Grande has been indelibly altered by the struggle. Yet this case is unusual, because defenders have recently won an important victory: the government declared the continued exploration and proposed mine at Rancho Grande’s El Pavón site to be “non-viable,” halting its development at the exploration stage. The declaration will bar open-pit gold mining from the pristine watershed along the Rio Yaoska – for now.

Contrasting discourses

Since launching their Nicaraguan operations in 2009, B2Gold has been implicated in numerous protracted community conflicts with unions, small-scale miners, and community groups. In Santo Domingo, where the company owns an open-pit mine, the current conflict involves displacing an entire neighbourhood to a new, brightly painted but treeless suburb, enabling the company to blast open the Jabali Antenna, a gold vein underlying the houses in one part of the town. Community resident Wakidia describes how B2Gold’s “community promoters” visit her home up to four times a day, patting kids on the head and handing out candy, while offering residents loans, scholarships, and business opportunities to make the move more palatable. Wakidia doesn’t want to leave, but many others have acceded to the deal, she says, and had “their homes bulldozed within hours of them leaving.”

B2Gold’s website frames its mining work in Nicaragua squarely in the realm of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and “responsible mining,” described by the company as making “positive impact in the communities where we work.” In 2015, the business and export community of Nicaragua (APEN) awarded B2Gold its social responsibility award in recognition of the nearly US$25 million that the company had invested in social projects between 2011 and 2015, and hailed the “relocation” of Wakidia’s neighbourhood as exemplary.

The local anti-mining land defender movements Guardianes del Yaoska and Salvemos Santo Domingo tell a different story – one of an aggressive, manipulative company that discredits and criminalizes them for their opposition, and uses intense community pressure, infiltration, and complex buyouts involving local and national politicians, state institutions, the media, the police, and the army. Indeed, in the same period of 2011–2015 during which B2Gold was showered with accolades, dozens of peaceful community protests against B2Gold were quashed, with many serious confrontations involving arrests, beatings, and in one, the death of a police officer.

There are thus contradictions in the ways that various parties describe events and the triangle of relationships among B2Gold, the communities, and governments. While doing this research with the Humboldt Centre in Nicaragua, I spoke with over 40 people* whose stories unravel the tightly controlled narrative in B2Gold’s promotions and reporting, revealing a company and a state doing whatever it takes to protect their reputations and the bottom line.

Criminalizing guardianes’ dissent

Originating from the astute observations of the Catholic priests and awareness building of NGOs in the area, the campesino-based guardianes formed as a local, multi-faith, multi-party (non-affiliated) anti-mining movement that follows principles of peaceful resistance and supports the local agricultural tradition. The local Catholic priests and the diocese offer integral support.

The guardianes report that local politicians have accused them of being opposition party-led, a charge that hardly holds, given its multi-party membership. In Nicaragua, though, discrediting a movement or individual can range from accusations of being anti-Sandinista to anti-progress, or both, which grants the government or party reason to surveil and harness state police and military forces on the pretext of keeping law and order. Many of the guardianes I spoke with told me of both veiled and explicit threats: phone calls and texts with death threats, warnings of repercussions for family members who worked for the government, and the sporadic unwarranted presence of anti-riot squads in the town.

A representative case was that of Ernesto – a farmer, historic-militant Sandinista, and guardian. Ernesto explained to me that in 2013, after years of quiet threats, an agent of the security branch of the national police appeared at his home. For a week, he was followed and spied on, and ahead of a planned anti-mining mobilization, she gave him “fair warning” to stay at home. Ernesto attended the protest anyway. While he was there, she phoned him, warning that there was a plan afoot to catch him with something that had been “planted” at his house. Ernesto later returned home and found nothing unusual. But at midnight, a truck rolled up, headlights off, stopping only long enough to recover something from the ditch. The case was reported to the national human rights tribunal (CENIDH), which condemned the harassment Ernesto faced, as well as similar incidences and allegations that others experienced – suggesting that the criminalization of dissent has not been isolated to Ernesto’s case.

A new mining climate in Nicaragua

One of many countries bowing to the World Bank, the IMF, and other trade liberalization proponents in the past 20 years, Nicaragua rewrote its mining law in 2001, inviting increased foreign direct investment (FDI). When Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega introduced a new fiscal policy in 2009, Nicaraguan gold exports quadrupled in five years. By 2012, gold was the country’s third most important export commodity. By 2015, Nicaragua’s ratio of FDI to GDP was third highest in the region.

President Ortega, erstwhile socialist, had returned to power in 2006, institutionalizing populist and clientelist politics while welcoming foreign mining investments by changing mining laws and tax regimes. According to a report commissioned by the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, in 2012, Dundee Capital Markets ranked Nicaragua second to Chile in favourable mining climate ratings.

The municipal elections of 2008 – widely regarded as rigged – resulted in a Sandinista sweep of mayoral offices across the country, including in Rancho Grande. B2Gold had aggressively entered Nicaragua in 2009 to take advantage of global gold prices, which in 2011 hit global record highs. The El Pavón concession in Rancho Grande, purchased by the company in 2009, was looking promising, but local resistance was strong.

Social responsibility and social licence

Events in Rancho Grande are unfolding in an unprecedented global era of resource neo-extractivism and what has been called a “new gold rush.” Spurred by corporate capital’s insatiable thirst for profit, record-high gold prices, new mining technologies, the rewriting of labour, environmental and tax laws, and ongoing global neoliberal restructuring that both obliges and supports increased FDI, Latin American states of all political stripes have increasingly reverted to mining as a principal development strategy.

Canada is central to this global mining trend. Canadian mining corporations operate in 100 countries, including in every country in Latin America. As of 2013, 57 per cent of the world’s public mining companies were listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange and TSX-Venture Exchanges,* and the Toronto Stock Exchange raised $969 million in equity capital for Latin American mining projects in 2013. The Canadian state has continued to reveal its colonial and imperialist support of Canadian mining interests in Latin America by providing financing and insurance through Export Development Canada, foreign aid through Global Affairs Canada, and assistance with redrafting mining legislation.

Unsurprisingly, reports by both the industry and its critics document that the ascendance of Canadian mining interest in Latin America has simultaneously increased social conflict.

Largely in response to denouncements in the 1990s by human rights organizations, labour unions, and environmental groups, the idea of corporate social responsibility has become a buzzword in this new mining environment. CSR is key to B2Gold’s corporate image.

Critics claim that CSR is a public relations strategy that is generally incompatible with social development, and that it co-opts social justice language and progressive NGO practices within communities. In theory, CSR aims to promote responsible, sustainable mining and contribute to the social development of mining communities. In reality, CSR often involves corporations engaging in spurious practices and investing in token projects to attain what they perceive as good relationships within the communities where they operate – thus allowing them to claim they have a social licence to operate (SLO).

SLO is a newer concept than CSR, an even more slippery phrase. The Fraser Institute’s Mining Facts website suggests that SLO is primarily about relationships that, rather than involving actual practices, are based on principles of good corporate behaviour. In mining companies’ eyes, SLO essentially gives them legitimacy and implies consent. In the B2Gold case, consent seemed to start and end at gaining signatures.

Social licence or social manipulation?

Following B2Gold’s arrival, the guardianes collected 7,000 signatures in opposition to the mining operation and presented the list to the National Assembly. According to the guardianes, B2Gold desperately wanted to counter the petition, and they began collecting their own signatures in an effort to show they had the requisite social licence to move forward on the project. Signatures became a new currency for the company, and methods to gather them an erratic, opportunistic composite of company promises of loans, scholarships, projects, programs, and even, according to witnesses, confirmation of receiving clinic visits or vaccinations from the Ministry of Health.

B2Gold had the Ortega government’s full support, but significant local dissent was growing. In 2013, the governing Sandinista party organized a “re-education” campaign, busing 150 political secretaries from Rancho Grande to Managua, the capital, for sessions expounding on the importance of mining – and of promoting mining within party ranks. Local leaders were warned of the consequences of not following party policy on mining; simultaneously, ministry personnel were told to step in line or be replaced. All were instructed to support B2Gold’s gathering of signatures by whatever means they could.

But the company had an additional tactic in their “community relations” department: they hire locals like Elfrain to create social licence in communities.

Elfrain’s story

Elfrain was introduced to me outside his latest business venture in Managua – a bar and billiard room. Sporting a grimy white tank top and shorts, reeking of sweat and beer, he was alarmingly candid about his stint of work with the company. Elfrain grew up in Bonanza, an infamously poor mining town in Nicaragua, where, he said, “fish were blasted out of the water using dynamite left around the mine,” and where children came into contact with municipal garbage receptacles made of cyanide barrels. He had moved to the capital city during the Sandinista revolution, trained as an agronomist, fought for the Sandinistas in the counter-revolutionary war, and worked under agrarian reform. Like many other public-sector workers, he had been “structurally adjusted” out of a job in the early 1990s, taking whatever he could get after that, including many jobs for NGOs working with rural farmers.

Elfrain’s background, experience, and intuitions about rural people made him an ideal candidate to work in community relations for B2Gold. By the time he was hired in 2013, he had long abandoned any development ideals, political principles, or parties. As he put it: “You just had to know how to approach people for that kind of work.”

Elfrain’s B2Gold boss encouraged him to replicate NGO practices to gain trust. A source at Asociación para la Diversificación y el Desarrollo Agrícola Comunal (ADDAC), a local agricultural NGO with extensive experience in the area, said that B2Gold not only copied but actually undercut the work of local NGOs. For instance, according to Elfrain, seeds from ADDAC were purchased through an open bidding process, sold at a standard fair and low price, and incorporated into a whole package of support and training for organized groups of farmers. B2Gold, on the other hand, would sell their seeds to anyone, and for less money and no obligation beyond signing a receipt.

Elfrain was also asked to use the known tactics of many former populist governments, presenting clothing and branded gifts to community leaders, and Christmas gifts for kids. He was hired to provide what he called “counter-therapy” for community opposition to the destruction of the environment. Told by B2Gold to “be like Chile,” he was to position B2Gold as a “green mining” company. If he managed to convince people of the messaging and get their signatures – using the sale of seeds, records of attendance or any other means – he was rewarded with bonuses.

Elfrain’s job to convince people was essentially about creating a veneer of social licence that would permit the company to smoothly meld the exploration phase into an operating open-pit mine. He described it as a “soul-buying exercise,” and he took it on with verve. His own soul was the first to be bought. For many years, the Catholic Church and the mining company had been declared enemies, and the company knew that the church held great power over public opinion. So Elfrain’s boss obliged him to attend mass on Thursdays, ostensibly to thaw icy relations by offering company support for things the church needed; strategically, the goal was to gain access to the church’s community radio. Perhaps most importantly, Elfrain was to report back “what was being preached from the pulpit.”

His stint with the company was short, but the guardianes remembered him with scorn, as a weasel-like character, making promises that they knew the company would never fulfill. Elfrain didn’t tell me why he left the company.

Ortega’s about-face

From 2013 to 2015, as B2Gold grew more aggressive across the country, growing tensions spurred violent strikes in their El Limón mine, and protests and police beatings in Santo Domingo. The guardianes in Rancho Grande likewise reported a heightening of stakes and tensions. Open meetings and protests in that period involved incidences of counter-protests paid for by the company, increasingly grave threats, the arrest of a community development worker (she was later dismissed for denouncing human rights violations), and firings of at least three government employees – ostensibly for expressing dissent.

In October 2015, evoking the papal encyclical Laudato Si’, the bishop of Matagalpa, a coalition of NGOs, and the guardianes organized a 15,000-person march in Matagalpa. The next day, Ortega called the bishop by phone to declare that El Pavón exploitation permits would not be granted, given the assessment of a study of the social and environmental sensitivity of the area. But according to the bishop and the Humboldt Centre, there had never been such a study. Indeed, for the guardianes, B2Gold had neither environmental nor social licence.

Why the government’s about-face? Speculation abounds: perhaps the violent confrontation in another B2Gold mine needed to be countered, as it was receiving negative international press; perhaps a political calculation ahead of the November 2016 election played a part. Maybe the role of the clergy in support of the guardianes played a role in influencing the Catholic governing party; however, few deny the astounding force of resistance mounted by the guardianes themselves.

Paradise preserved

The community of Rancho Grande has won an important victory and – for now – is protected by the declaration of non-viability, keeping its water supply clean, its ancient trees uncut, and its organic food supply and traditional agricultural practices intact. Padre Pablo, speaking to a national symposium on mining in November last year, summed it up thus: “The mountains, forests, and rivers are still our wealth and the magnificence of our land a natural asset that we must continue protecting. I dare say that we have [in Rancho Grande] a piece of earthly paradise – that only just yesterday we had in all of Nicaragua.” No mining company should ever have the right to destroy paradise.

*This sentence has been modified from the print version to reflect a more accurate figure. The print version reads: “As of 2014, about 80 per cent of the world’s mining companies were headquartered in Canada,” which represents an error in fact-checking and is the fault of the editor, not of the author.

The author acknowledges support from the Humboldt Centre, Managua, Nicaragua, and assistance from Kate Ross-Hopley, U of S medical student.