America’s feudal fascination with a southern border wall would soon exhaust itself if not for the existence of another barrier: a curtain of ignorance through which few news stories cross to reach an English-speaking North American public. When stories do break through, they tend to burst and fade without context, the seemingly senseless eruptions of a seemingly senseless violence: a journalist killed, a mayor assassinated, 43 students forcibly disappeared, mass graves, narco turf wars, barricades of burning tires. Nothing, certainly, to suggest that some of these deaths might be casualties of a war being waged against a rebellious populace in the name of a corrupt political system pushing a discredited economic model. North of the border, those imposing the same failed model would prefer we pay no attention to the blood seeping from beneath the curtain.

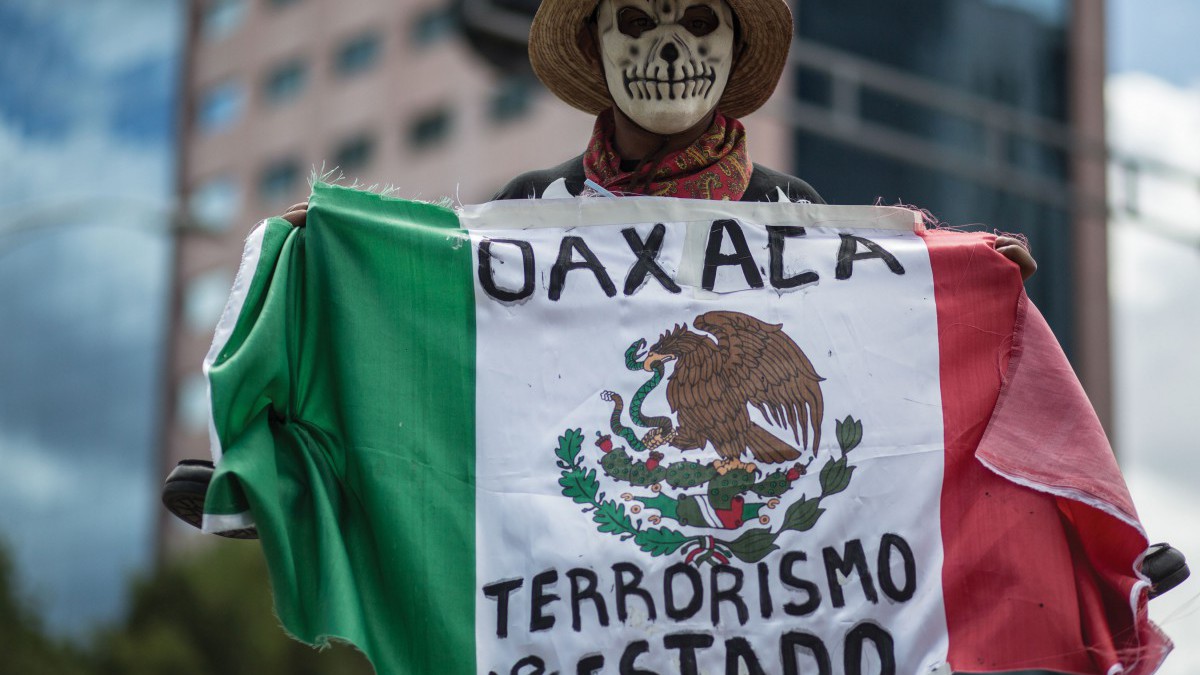

In June 2016, for example, came news that 11 people had been killed in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca, shot in the streets by federal and state police. In a massive state-wide operation, police had attacked barricades erected by teachers and their supporters to protest neoliberal education reforms – the latest flashpoint in a widespread, teacher-led uprising that has persisted ever since the 2013 passage of an education reform package. This uprising should be followed closely, not least because in its uncertain outcome we might glimpse the contested future of public education closer to home: the triumph of a for-profit model that sifts students’ access by their ability to pay, or entire communities rising up to defend, expand, and improve public education. One way or another, neoliberalism will make radicals of us all.

Teachers in four southern states and parts of Mexico City have been on strike since May 2016, the latest flare-up in a three-year battle to see the reforms repealed. The strike continues as of the time of writing, having held through the rains of summer and well into the fall term. The striking teachers’ main demand is the repeal of deeply unpopular reforms that they say open the door to privatizing public schools, loss of job security for teachers, the weakening of the largest union in the hemisphere, and the defeat of the democratic faction within the union that is leading the strike. Roads, railways, shopping malls, and airports have been blockaded. Town squares, government buildings, highway toll booths, and TV and radio stations have been occupied. School gates, plastered with supportive messages from parents, remain closed. Requested meetings with the government have gone nowhere. Particularly since the June massacre, entire communities across Oaxaca and Chiapas have mobilized and are now organizing themselves through general assemblies, reminiscent of the 2006 Oaxaca commune, which was likewise sparked by a brutal police crackdown on organized teachers.

The stakes could not be higher. If the reforms stand, the teachers’ defeat would further weaken Mexico’s already struggling labour movement and open the door to far more sweeping changes in other sectors. Deeply unpopular president Enrique Peña Nieto has staked his administration’s legacy on an IMF and World Bank-dictated neoliberal overhaul of sectors that include labour, energy, health, education, telecommunications, finance, and others. Forcing the government to reverse its education reforms would effectively empower social movements to challenge the entire package – which is precisely what the federal government fears, having already signed international agreements committing Mexico to this path of deepening deregulation and privatization.

Banking on education

On July 27, 2016, Luis Robles Miaja, president of the Mexican Banking Association and chairman of the board of directors of BBVA Bancomer, Mexico’s biggest bank, stood at the front of a large room in Mexico’s presidential palace, flanked by the president of Mexico, to address several dozen Grade 6 students, whose high placement in the Children’s Olympics of Knowledge competition qualified them for this honour. Robles Miaja lectured the students (and more relevantly to his purpose, the assembled journalists) on the virtues of the education reforms that had been passed when the students were back in Grade 3, and denounced those who opposed the reforms.

“Enough!” thundered Robles Miaja. “The welfare of the nation cannot be held hostage to the questionable interests of a few.” (The assembled students met the banker’s lengthy harangue with an evident agony of boredom.)

Whose “questionable interests” are actually served by this reform, which is so popular with Mexico’s banks that its 2012 launch was first announced in the foyer of one, because the Congress was then under siege by educators concerned about the welfare of the nation?

Well, one measure that Robles and BBVA Bancomer surely appreciated was the government’s decision to shift the financing of school infrastructure from the public realm to the speculative market. “In December 2015,” Renata Bessi and Santiago Navarro F. report, “the first educational bonds or National School Infrastructure Certificates, CIEN, were issued by the Mexican Stock Exchange, which investors BBVA Bancomer” – the bank Robles Miaja heads – “and Merrill Lynch purchased for 8.581 billion pesos, approximately US$457 million.”

More generally, the education reforms – which were pushed by the OECD, the Washington-based Partnership for Educational Revitalization in the Americas, and the right-wing lobby group Mexicanos Primero (Mexicans First), and passed with the support of Mexico’s three largest political parties – seek to treat education as a commodity rather than a human right. The reforms required that Mexico’s constitution, which since 1917 had guaranteed free universal public education, be changed to allow schools, chronically underfunded by the state, to seek funding from private sources, including parents, to maintain programming and equipment.

As the Mexico City section of the striking teachers points out, this legislation “opens the door for … the de facto legalization of fees, allowing the entrance of businesses into schools and turning the constitutional provision guaranteeing free public education into a dead letter. This has a name: privatization.”

A number of the reforms seem to have been drafted with the express purpose of imposing labour discipline on teachers and undercutting their union protections. Following upon an earlier reform that imposed standardized tests on students, the 2013 reforms introduced annual tests for teachers, and tied their continued employment to their test performance – a concern for teachers in Indigenous communities who fear that a test designed by bureaucrats in Mexico City would be a poor measure of their often multilingual performance, their capabilities, and their role in the community. Teachers can now be fired for participating in strikes. Anyone with a bachelor’s degree can now teach in Mexico’s public schools, calling into question the future of Mexico’s system of teachers’ colleges (normales). (Rural normales like Ayotzinapa offer campesino and Indigenous youth a rare path to employment in their communities, and have long been a thorn in the side of the state for their strong legacy of political education and activism.)

The three years of struggle following the passage of the reforms have only strengthened the perception that their true goal is to weaken the power of organized teachers. Since the latest strike began, the secretary of education has fired at least 580 teachers for participating in the strike (and has repeatedly threatened to fire thousands more), has frozen the accounts of the striking union and blocked it from collecting dues from members electronically, and has arrested four union leaders and issued warrants for two dozen others. Combined with the impact of the reforms themselves, these measures threaten to drastically weaken the independent organizing capacity of Mexico’s teachers.

Such a defeat would represent a calamitous blow to the country’s moribund labour movement. Since the 1940s, Mexico’s unions have been overwhelmingly dominated by corrupt charro (literally “cowboy,” but meaning clientelist) unions affiliated with the long-ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). The teachers’ union is no exception to this servile corruption, as we’ll see: remarkably, those teachers engaged in the strike are facing down not just the violence of the state and an overwhelmingly hostile media, but the very union that represents them at the national level, as well as at the state level in most states. Striking teachers are, therefore, waging a two-front war: against the federal government’s reforms, and against the perfidy of their own national union.

Strikes and counter-strikes

Every teacher in Mexico – all 1.4 million of them – is a member of the Mexican teachers’ union, known by its abbreviation as “el SNTE” (pronounced el sentei). Since its formation in 1943, the SNTE has served as a clientelist puppet of the PRI. In February 2013, the union’s spectacularly corrupt then-president, Elba Esther Gordillo, was arrested for, of all things, corruption, but only after having made disapproving noises about the proposed education reforms. Since then, under new but not different leadership, the SNTE has supported the reforms, defended the repression of striking teachers, and stood in as the “responsible” voice of teachers any time the government wants to make a show of consulting them (which is rarely).

So, who is organizing the teachers’ strike, then, if not the teachers’ union? The National Coordinating Committee – known, confusingly, by its very similar abbreviation as “la CNTE” (pronounced the same as el SNTE except for the feminine article). Since 1979, the now 200,000-strong CNTE, a direct action-focused democratic formation within the SNTE – a union within the union – has been organizing against corrupt governments and corrupt union leadership in many states and at the national level, at a cost of 151 teachers’ lives over the first few decades of its existence. The CNTE is strongest in the south – the majority-Indigenous state of Oaxaca, as well as Chiapas, Guerrero, and Michoacán – where it has long been at the forefront of social protest movements, regularly initiating encampments in central squares and blockades of highways and strategic targets.

Increasingly, however, the CNTE has taken its struggle to the national level. As María de la Luz Arriaga Lemus points out in NACLA, the nature of the education reforms, which centralize control under the federal government and tie the hands of state governors, has forced the CNTE to organize nationally rather than focusing its demands, as it could in the past, on those states where the CNTE has won democratic control of the state machinery of the SNTE. This has led, recently, to growing support for the CNTE well beyond its historical strongholds in the south. As a result, the CNTE’s long-standing objective of “reconquering the SNTE so that it serves the interests of the grassroots and not those of the employer” has moved to the fore.

In the central state of Zacatecas, for example, the CNTE nearly achieved its goal of “reconquering” the SNTE at the state level this summer. As the SNTE’s state convention opened, it quickly became clear that delegates aligned with the democratic CNTE boasted a two-to-one majority in the room, and stood poised to take over the union leadership in that state for the first time in the CNTE’s 37-year existence.

Before the real business of the convention could get underway, a vote was held on who would chair the meeting. When the clear majority in the room was ignored and the leadership’s hand-picked candidate was named chair, objections were raised and one delegate called from the floor for a recount.

Suddenly, suit-clad security guards, contracted by the SNTE, surrounded and harassed the challenger, and then began throwing chairs at, beating, and Tasering the delegates, some of whom threw chairs back, bringing the day’s proceedings to a grinding halt. Fifteen teachers were injured. The bizarre scene was caught on video, as were interviews with teachers injured during the brawl (though, typically, the scant international coverage presented the skirmish as simply a senseless eruption of violence among thuggish teachers).

Police, amassed outside, opted not to intervene, despite appeals from teachers to restore the peace. Late that night, the SNTE’s own lawyer, not a teacher herself, took to Facebook to announce that she would serve as the next president of the Zacatecas section of the teachers’ union – a solid affirmation of the status quo in the face of a violently suppressed democratic challenge by the CNTE.

Incidents such as these suggest that the SNTE’s grip on power is growing increasingly tenuous. Chair-throwing security guards, or simply an improperly counted vote, might be all that stand in the way of a democratic reclaiming of the Mexican teachers’ union (the SNTE), state by state, and perhaps nationally, if a democratic national convention can be forced on the leadership.

Meanwhile, in the southern states where the CNTE is strongest and the strike is holding, the democratizing potential glimpsed in that convention hall in Zacatecas extends to the entire society. After the June massacre in Nochixtlán, Oaxaca, in which eight were killed and 94 wounded by gunshots from state and federal police (three were killed elsewhere in the state), the community response was swift. More blockades went up around the state and beyond, thousands marched in the state capital the following day to denounce the violence, and civil society mobilized in impressive numbers to support the teachers and their strike. Neighbouring Chiapas saw similar levels of community mobilization.

Indeed, each new assault on striking and protesting teachers has only fuelled the resistance, as the past three years have seen a steady escalation of marches, blockades, and occupations demanding the repeal of the reforms and the participation of teachers in shaping the future of education. Meanwhile, parents and communities, particularly in the south of the country, have increasingly stepped up in support. In Chiapas, for example, the Democratic State Committee of Parents announced in July its participation in the National Gathering of Parents in Defence of Education and Against Structural Reforms, declaring, “we’ve got to structure ourselves, above all, to map a path of action to throw out all these reforms and we will walk not just with the teachers, but also with the farmers, the workers, the doctors, the transportation workers, the churches.”

The struggle is not merely defensive, however, but also seeks to right some historical wrongs written into Mexico’s revolutionary 1917 embrace of free, universal education. In the statement of support drafted by a general assembly of the communities of the Sierra Juárez region of Oaxaca, the community called on teachers to push forward with true educational reforms that serve the needs of Mexico’s diverse communities and that might go some way to repairing the historical wrongs of Mexico’s education model: “We also call on the Oaxacan teachers to resist with responsible proposals, to build educational alternatives and resistance from inside the classrooms. Do not forget that in the recent past, teachers were used to manufacture a single national culture that Indians had to integrate into, which after sixty years of this policy has resulted in half the population that considers itself [I]ndigenous and that represents 66% of the total population of Oaxaca does not speak their original languages, nor do the textbooks include the knowledge built up by our ancient cultures. We will no longer allow for this supposed modernity to distort us, [and] in this sense, teachers have the great task of rescuing and strengthening our identities.”

In this increasingly fraught three-way standoff between the Mexican government, the corrupt SNTE, and the radical CNTE, something must give. Perhaps the likeliest outcome is that the CNTE, disciplined and well organized but lacking an electoral vehicle to push its demands, will ultimately fail to see the reforms repealed, strikers will be purged with the SNTE providing the scab labour to fill the gap, and the accelerated imposition of neoliberal narco-capitalism will continue against an increasingly unequal, increasingly terrorized, yet still courageously mobilized society. However, the remarkable tenacity and steady expansion of struggle by the teachers and their allies over the past three years points to another possible outcome: the democratization and radicalization of the Mexican teachers’ union, the successful rollback of the unpopular reforms, and an emboldened grassroots movement for universal public education. Those of us watching from the other side of the curtain can only hope for the latter outcome. And either way, we have much to learn about how to organize to defend and improve public education, and what is at stake in that struggle.

RECOMMENDED READINGS

- Scott Campbell’s regular coverage of the strike and related social movements, all of which can be accessed on his blog, Falling into Incandescence.

- María de la Luz Arriaga Lemus, “The Struggle to Democratize Education in Mexico.” NACLA, Fall 2014.

- La Botz, Dan. “The Long Struggle of Mexican Teachers.” Jacobin, August 10, 2016.

- Teaching Rebellion: Stories from the Grassroots Mobilization in Oaxaca. PM Press, 2008.