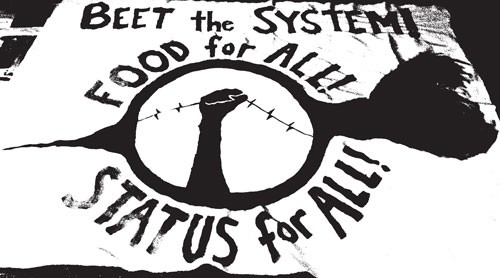

Eating is an incredibly intimate act. Necessary for survival and intricately intertwined with our emotions, spirituality and culture, food holds major power. As such, the systems that govern its cultivation, distribution and consumption are fertile battlefields for controversy, domination, generosity and resistance.

Naturally, power-hungry corporations have seized every opportunity to profit from the production and distribution of food. Corporate control over our food systems has led to widespread devastation. The current famines in the Horn of Africa, the diabetes epidemic among Indigenous peoples on Turtle Island and the fact that 80 per cent of the world’s hungry live in rural areas are but a few current examples.

Even those who have managed to maintain some degree of sovereignty over their food by sourcing their nutrition as much as possible from nature through hunting, fishing, gathering and gardening are thwarted by contamination of their food sources. The massive oil spill on Lubicon Cree territory in northern Alberta this April and the contamination of fish in the Athabasca River downstream from oil sands development are two examples of food sources becoming inedible due to industrial contamination.

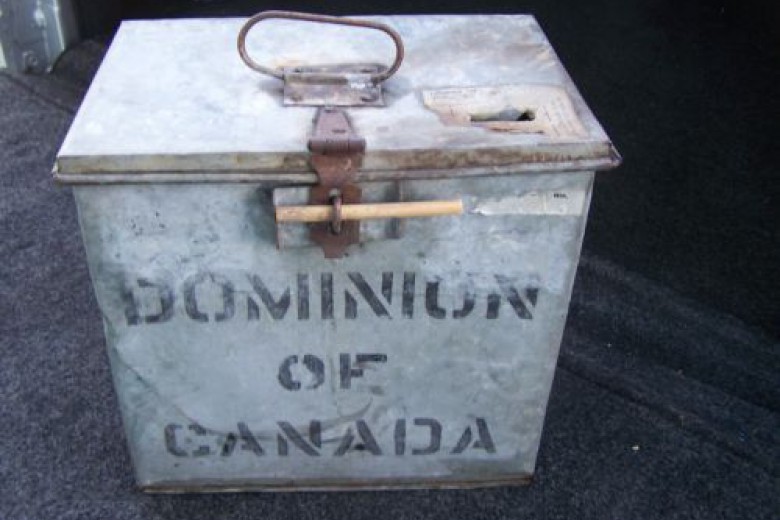

Building a sustainable, equitable and inclusive network of food systems to replace our current industrial model is no small task and the current food movement is still struggling to escape the powerful influences of the capitalist, colonial ideals that are so engrained in all of our systems. As you’ll read in this issue, the local food movement has yet to come to terms with the long distances traveled by the farm workers who often grow local food under precarious conditions; the fair trade movement has in many ways come to reinforce the colonial power relations it originally sought to resist; and our government continues to pursue policies and support projects that compromise the food security of people in this country and elsewhere, as for example with their dogged pursuit of the Canadian-European Trade Agreement, their dismantling of the Canadian Wheat Board and their support of biotechnology development in Vietnam.

Despite these challenges, people have begun to reclaim control over their food and food systems in astonishing numbers. The food movement in this country and globally is broad, dazzlingly diverse and unique. As Charles Levkoe explains on page 19, unlike other social movements, the food movement is remarkably decentralized – a kind of organized chaos of multiple movements that feed into and draw from one another. Taking root in backyards and balconies, acreages and greenhouses, community kitchens and gardens, and in the hearts and hands of millions of people who are waking up en masse to the potential, and in fact the necessity, of cultivating food sovereignty, the food movement is a force to be reckoned with.

This issue’s centrefold offers a small but tantalizing sampling of 20 food-related initiatives under way across the country. In compiling these profiles, I spoke to dozens of foodies and community leaders who are each driving their own piece of the movement in their own community. If the tangibility of their passion, the diversity of their interests or their stalwart dedication are any indication, the food movement is in good hands.

Our food systems embody considerable potential for the powerful and the marginalized alike. Because it is essential to our very existence, those who control food control people. And when we reclaim control over our food systems, we open up the possibility of asserting our power in other spheres as well.