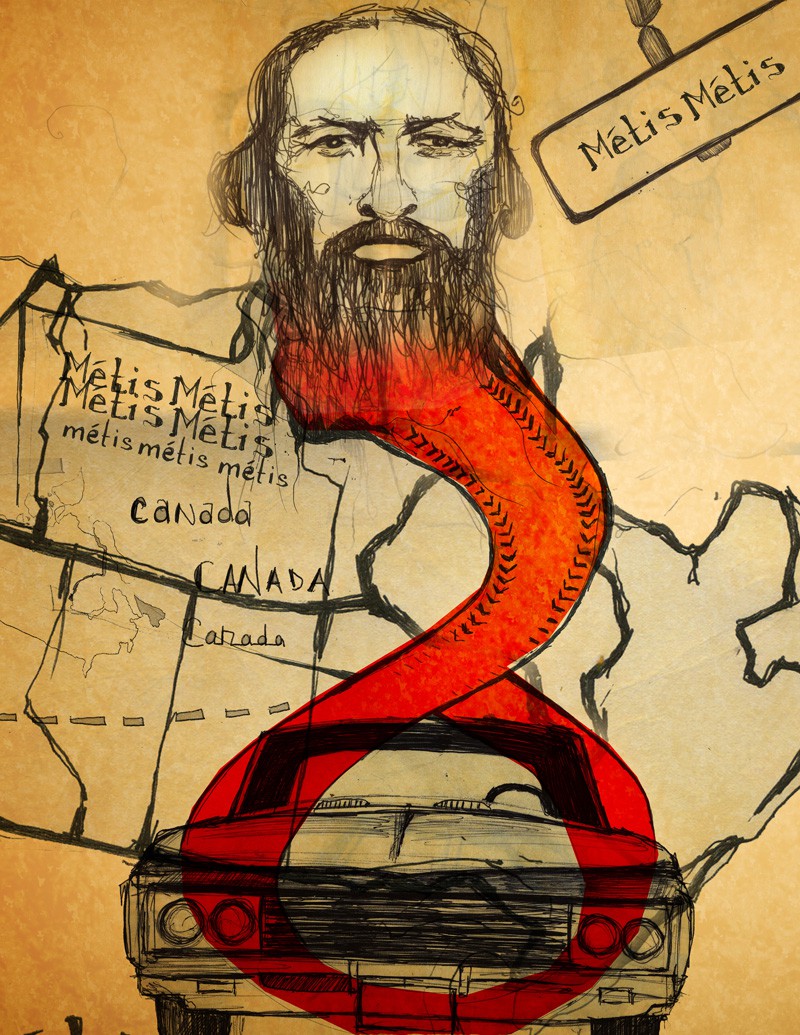

The car engine hummed as I headed east on the Trans-Canada. It was late August, and the wind bashed against the car in waves. Always the wind on the prairie. And on that day, it made me feel energized, alive. On that day, I was driving back home to Regina, and I was driving back home a different person.

Earlier, I had been at the Métis Local #160 in Moose Jaw. I had sworn an oath, had my picture taken, and been registered as a Métis citizen. It was 2010, the Year of the Métis in Canada, and at 35, I had a new identity. As I rushed home in my car, I wondered what my life would be like from then on. I wondered who I was about to become. I sensed change, prickly and persistent. The highway stretched out long and far in front of me.

*

A few weeks later, my identification card arrived in the mail. I placed it in my wallet so that the edge that read Métis Citizen stuck out from the pocket that held it. And for a while, I felt satisfied. I had proof. But soon, that satisfaction faded and doubt took root. Was I Métis because a plastic card said I was? I ignored the doubt at first, but it burrowed in. Got stuck. Then I learned from census statistics that the fastest-growing population in Saskatchewan is the Métis population – it doubled between 1996 and 2006. This growth has been attributed in part to people discovering their Métis heritage after a time in which it had been buried or forgotten, when racism and assimilation efforts made it shameful, and even dangerous, to self-identify.

I will never know exactly why and when my own family’s Métis history was buried; I only know that it was. I grew up in the Qu’Appelle Valley, a place with a long history of Métis settlement, but I had never even heard the term Métis as a child. It wasn’t until I was an adult and my mother was given a binder of historical documentation from my great-uncle that I learned my ancestors were Métis. I thought about these census statistics, about all the people like me who had just discovered their history. Then I thought about all the people who have lived their entire lives as Métis. What do they think of people like me?

American scientist Geoffrey C. Bowker and sociologist Susan Leigh Star write that “to classify is human.” And humans have a history of using written documentation, like identification cards, to do it. Other researchers have argued that identifying groups of people meets both practical and social needs – practical because it simplifies interactions with others, including governments, and social because it satisfies the need to belong. Sociologist Erving Goffman further explained that people use information about themselves as a form of self-expression that contributes to identity formation. Written documentation, therefore, contributes to a person’s understanding of themselves. This made sense to me. But I began to realize that my own confusion and uneasiness regarding the Métis citizenship card in my possession stemmed from the fact that I didn’t know anything about the group of people I was now supposed to belong to.

I started to attend Métis cultural events and social gatherings. I joined Métis community groups and started to learn what I could about the culture I now identified with. And as I began to meet and forge relationships with other Métis, I discovered that many Métis, including Elders and leaders in the community, did not have Métis citizenship cards. Some even refused to apply for them.

“I’ve filled out the application,” Ashley Norton says, “but I’m reluctant to send it in.” Ashley is a founding member of the Wiichihiwayshinawn Foundation, Michif for we are helpers, in Regina. The organization was formed to empower, preserve, and develop Métis community and culture by providing educational workshops and scholarships, and hosting an annual awards celebration to acknowledge the achievements of Métis community members.

Part of what holds Ashley back from sending in her application is that she feels she doesn’t need anyone to tell her she’s Métis. But it’s also her sense of loyalty to her family.

“I’m not sure the Norton side of my family would qualify,” she explains. Her grandmother is Dene First Nation and her grandfather is English, and even though they live traditional Métis lives and are accepted by the community, they don’t have the genealogical connection to the Red River Settlement that the Métis Nation citizenship application requires.

The current Métis registry process, established in 2004, requires that applicants have an ancestral connection to the historic Métis homeland, which includes Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia, and parts of the northern United States. It does not include Quebec, the Maritime provinces, or the vast majority of the Yukon, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut. Because the Norton side of Ashley’s family are Dene and their traditional territory is in the North, they wouldn’t qualify. The other side of her family does have ancestral connection to the historic Métis homeland, but Ashley still questions sending in her application.

*

Tammy Vallee, a genealogist who works at Métis Nation – Saskatchewan, the governing organization for Saskatchewan’s Métis citizens and the organization responsible for the province’s Métis registry, says the identification cards are separate from identity.

“It’s not our job to say someone’s not Métis,” she says. “We just say that we can’t give them a card.” Tammy emphasizes that the process is not meant to infringe on how people define themselves. “Identity is identity, and we don’t want to take that away from anyone.”

In a way, this makes sense, but it’s cold comfort for Ashley, whose family ties are strong. “If my whole family can’t register, why should I?”

Allen Parenteau also hasn’t registered out of loyalty to his family. Allen is a community leader and an instructor at a Métis educational institute. Because of the institute’s ties to the Métis Nation – Saskatchewan, he asked for a pseudonym. Allen’s family does come from the Métis homeland; however, he feels the registration process is too complicated for the Elders, and if they can’t register, he won’t either. “Until the process is made easier for them, I can’t. I’d feel almost as if I was betraying them.”

But he still sees the need for a registry. “Don’t get me wrong. Counting us is a good thing because you can’t have a discussion around rights until you know how many of us there are. And I advocate for the registry in my classes. It’s important. But the registry process itself is what I have issue with – it’s a very white, bureaucratic process. It’s as if a white judge has come along and said, ‘I know what’s good for you.’ ”

In many ways, Allen’s correct. The current registry process stems from the 2003 Powley case in which the Supreme Court of Canada determined that the Métis possess an Aboriginal right to hunt. Aboriginal rights refer to the traditions, practices, and customs unique to each Aboriginal group that ensured their survival, including the right to hunt, fish, trap, and gather. They also include language rights, the right to exercise Aboriginal religions and culture, to self-government, and to benefit economically from the lands on which Aboriginal peoples were historically dependent.

In R. v. Powley, the Supreme Court of Canada also determined that the term Métis “refers to distinctive peoples who … developed their own customs, and recognizable group identity separate from their Indian or Inuit and European forebears.” But while this ruling resolved the Powley case, it raised another question: who is Métis? While individual Métis locals (organizations for specific communities, similar to constituencies) and provincial Métis offices kept membership registries over the decades, there had never been a single membership registration process for all Métis, regardless of local or province. After the Powley case, and with funding from the federal government, the Métis National Council and its five member organizations in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario developed a new registration system and began to register Métis citizens in 2004.

Because funding is based on a court case, Tammy Vallee explains, the Métis Nation had to use a “legitimate process,” one that would stand up in court. But there’s something uncomfortable in this justification. The criteria to determine who is Métis was created for the courts – not for the Métis themselves. That’s a huge concern for many in the community, and it’s why Allen considers the registry a “voiceless process.”

Jean Desjarlais, an Elder and respected Knowledge Keeper, echoes Allen’s concerns for Métis Elders: “Older people don’t have a clue how to start.” She asked me not to use her real name because of her connections to the Métis Nation – Saskatchewan through the community and her professional life. She thinks the current process is cumbersome, invasive, and degrading. Plus, she says, “I’m sick and tired of having to prove that I’m a half-breed – I’ve got five cards now that say I’m a Métis person.”

This is another issue many Métis people have with the registry process – there have been several other processes in the past, each one different from the other. Some Métis have a small collection of Métis Nation identification cards they’ve acquired through the years. I thought about that feeling I had when I had received mine and asked Jean if she remembered receiving her first one. She nodded. She was in her late teens.

“My mother came home from a meeting with cards for all of us. That’s how easy it was then. She told me, ‘They want to count us, and it might be important 50 years from now.’ ”

But almost 50 years have passed since that time, and there are still new cards and still more counting.

*

Calvin Racette’s concerns about the registry process run even deeper. Calvin is a Métis from the Qu’Appelle Valley and works as an Aboriginal consultant for Regina Public Schools. He grew up very proud of his Métis heritage and became involved in the Métis Society of Saskatchewan (now defunct) and worked for many years at the Gabriel Dumont Institute, which is dedicated to renewing and developing Métis culture. Throughout his years at those organizations, he was involved in researching Métis history, and he began to see how the definition of Métis changed over the years.

“In the beginning, it meant you had a white father and an Indian mother. Then in 1938 in Alberta, they developed a different definition with the Métis Population Betterment Act. In the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, there was the north-south split, and eventually the Red River Settlement idea came into being. But that’s left the northern Métis out.”

Seeing how the identification criteria has morphed and evolved over time has left Calvin feeling uncomfortable. He recognizes the political nature of the Métis Nation – Saskatchewan and believes that the decisions the organization made were about power and control, not right and wrong. Now, he refuses to get a card. He doesn’t want any identification or label attached to him.

“I call myself brown. Métis, First Nations, Aboriginal – those are all political terms created by government,” he says. “I don’t need a stamp on my ass to tell me who I am. Besides, identity doesn’t come from a political structure; it comes from the heart.”

His comment resonated with me. It occurred to me that Calvin had hit on the real problem I was struggling with – I had looked to something external for validation. In that moment, I felt silly. Ashamed, even. And those feelings worsened the more I researched and learned about the complicated colonial relationship between Indigenous peoples and the Canadian state. I realized that the Métis Nation registry is still colonial at its roots. Glen Coulthard, a contemporary scholar of Indigenous politics, working from and expanding on philosopher Frantz Fanon’s work, suggests that when identity-based movements seek state recognition, such as the Métis Nation citizenship cards, they are giving power to the colonizer. In other words, by seeking recognition as Métis citizens from the courts – a colonial institution – the colonial relationship is maintained. This information was, and still is, difficult to process. I’ve thought about cutting up my card, denouncing it. But something won’t let me.

*

Over two years have passed since I first received my Métis citizenship card. I still struggle with the decision I made, but I have found some comfort. Frantz Fanon argued that the pathway to true self-determination lies in personal and collective self-affirmation. It’s a self-initiating process. During these past two years, I’ve gained knowledge about our country’s history and my own history, I’ve become involved in the Métis community, and, most importantly, I’ve developed new relationships. These are the things helping me to discover my Métis-ness. Not the card. While I recognize that the Métis Nation registry process is flawed and complicated, I absolutely do not regret registering. I know this is contradictory, and it’s hard to reconcile. But personally, I have to honour my citizenship card because there’s a journey behind it. A journey I’m still on. One that’s leading me to a new way of being in the world.