Imagine opening your morning paper to read the following:

“The Minister of Human Resources announced today that she will be working with the provinces to lower university and college enrolments across the country. ‘We don’t think young Canadians should be wasting their time with post-secondary education,’ the Minister said. ‘It’s not good for them and it’s not good for the Canadian economy.’”

Odds are that your reaction would range from shock and outrage to simple gobsmacked disbelief. Education is widely and uncritically accepted as wholly good for everyone – students, their families, society as a whole, and the economy – and the higher you go up the schooling ladder, the better. But whenever something becomes so obvious that to think otherwise appears ridiculous, perhaps it’s time to take a second look.

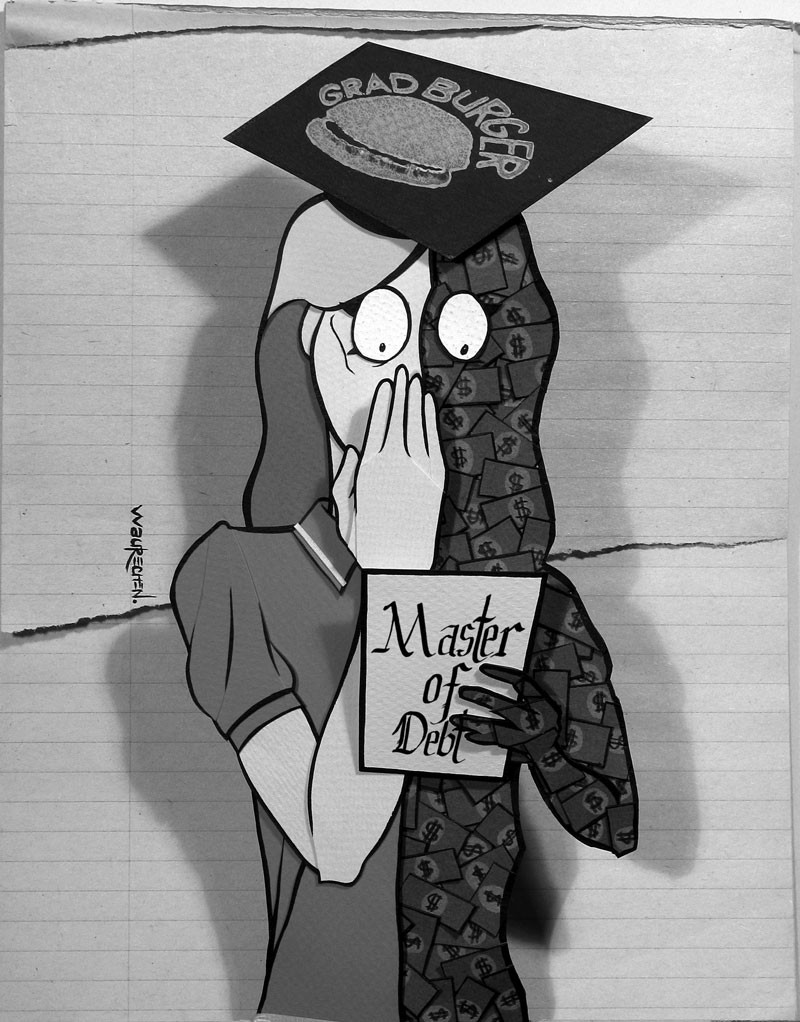

The Canadian post-secondary education system is now the site of so many core contradictions that it cannot possibly do the work we expect of it. Post-secondary students and their families are caught up in these contradictions and often invest vast amounts of money and time only to find that there is no pot of gold at the end of the post-secondary rainbow. The emperor may not yet be buck-naked, but he’s down to his socks and underwear – and it’s time we raised our voices to say so.

Our fixation on post-secondary education for all is relatively recent. In 1951, only two per cent of Canadian adults had any post-secondary training, but by 2001, over 50 per cent of the population had some post-secondary training. Much of this increase happened quite recently, with the number of Canadians aged 25-64 with a university degree doubling between 1991 and 2001. Many factors have driven this trend, including the growth of universities and colleges, the promotion of post-secondary education to larger segments of the public school population, the entry of women in large numbers to the workforce, and changes in the labour market.

Back in 1951, a university education was the preserve of the (mostly male) elite and wasn’t necessary for most people seeking work in any case. By 2001, there were many fewer jobs left for those who stopped at a high school diploma. Indeed, a post-secondary degree, diploma or certificate has come to replace high school as the minimum qualification for many entry-level jobs. It’s now a requirement for those seeking the well-paid, stable jobs needed to achieve the minimum markers of a middle-class standard of living: home ownership, private transportation, annual vacations, retirement savings and of course, enough money for their own children to access post-secondary education.

Even as this trend has accelerated, the job market has been moving in the opposite direction: manufacturing jobs have disappeared and haven’t been replaced by white-collar equivalents, leaving more and more graduates with fewer and fewer good employment options. In 1991, the Economic Council of Canada analyzed changes in the Canadian job market from 1967 to 1986. They concluded that the shape of the job market had shifted from being a pyramid (lots of low level, fewer mid-level, fewest high-level jobs) to being an uneven hourglass with a small bulge at the top, a big bulge at the bottom and a tucked-in middle. They argued that three-fifths of the jobs that had disappeared from mid-level positions had sunk downward, becoming less well-paid, less stable, often part-time positions with fewer benefits. Presciently, they suggested that these changes were not cyclical but were “fundamental and systemic.”

More generally, Canada has shifted its economic focus from the production of goods to the provision of services. In 1967, 40 per cent of Canadians worked in the goods sector. By 1988, the share had declined to 29 per cent while the service sector had grown to 70 per cent of jobs – and 90 per cent of all job growth since 1967. Statistics Canada recently concluded that between 2004 and 2008, one in seven manufacturing jobs disappeared, and by 2008, the goods sector accounted for only 23.5 per cent, while 76.5 per cent of all jobs were in the service sector.

Given shifts in public attitudes toward blue-collar work, this may not seem to be a bad thing, but “service” work runs the gamut from burger flipper at the local fast-food joint to “sales associate” at the mall to teacher to hospital administrator to civil servant. These are not equivalent types of work and not all of them make up for lost manufacturing work.

Despite the stigma surrounding factory work, these jobs were some of the best in comparative terms. Factory jobs consistently pay more than jobs in the rest of the economy. In 2008, for example, the average factory worker made $20.80 per hour versus $17.70 for all other workers. Factory jobs are more likely to be full-time – only four per cent are part-time in this sector versus 20 per cent in the rest of the economy. Finally, these jobs are more likely to be unionized, which usually means better working conditions, pay and benefits than non-union work. The average service sector job simply does not represent a fair trade.

Nonetheless, thousands of students enter post-secondary institutions every year hoping that they will buck the trend, get the right qualifications and find one of the increasingly scarce good jobs. With over 200,000 post-secondary education qualifications granted in Canada each year, the odds of this happening get longer all the time.

Jill Rogerson came back to university after a few years as a receptionist and typist in order to improve her job prospects. After five years of self-discipline and hard work balancing courses and weekly work commitments, she graduated with a double major in history and social anthropology, only to find herself still working at the same office. “I’ve learned a lot and I don’t regret that, but I’m not sure how this degree is going to get me a better paying job.”

Jill has found that in her fields of interest, including international development, employers often require experience or ask for a six-month unpaid internship before offering a paid job; even then, their jobs don’t pay as much as the one she’s got. She kept her student debt low by working throughout her degree. But now that the payment is due, she can’t afford to earn no salary for six months. “I don’t know where I’ll be in two years’ time. I put a lot of faith in getting a university degree but now I wonder if it was worth it.”

Jill is relatively fortunate because her student debt is manageable and she’ll probably be able to pay it off after six months to a year of full-time work. Others, like Mark Kalinin, are not so lucky. Graduating with a $36,000 debt meant that Mark could not realistically consider unpaid internships; he had to find a job fast. “I wanted to hold out for an entry-level job at an environmentally sound company – somebody doing really innovative stuff I could commit to. But after looking hard for a long time, I’m resigned to keeping my summer waitering job so that I can make my loan payments.” With total Canadian student debt at $13 billion, Mark is certainly not alone.

Still others are worse off than Mark and Jill. Mary Joosten is by all accounts but one a good student. She attends every class, takes copious notes, does all the assigned reading, participates in tutorials, hands in all work on time and devotes many hours to her studies. For all that, she is a low C student who constantly struggles to keep her average above the cut-off to remain at school. This is painful for her because she was an A student in high school and had never struggled academically. “The first time I got a C- on an essay, I burst into tears. I worked so hard on that paper,” she says. Mary can memorize but she can’t analyze information. Never having been asked to do this before, she has no experience upon which to draw. With hundreds of students in every one of her first- and second-year courses, there were no teaching resources to do remedial work with her. “I used to try to see profs in their office hours and volunteer to do extra work to make up my grades, but they didn’t have time to work with me – there were always lineups outside their doors – and they didn’t have enough teaching assistants to do extra grading.” She doesn’t cry at every C anymore but she’s worried about making it through as each level of study demands more from her.

Mary is caught in a political trap not of her own making. As high-school-only jobs disappeared and lost their appeal for young Canadians and as government funding for post-secondary education was slashed in the 1980s and 1990s, post-secondary institutions turned to tuition to make up the shortfall. Admissions at universities and colleges mushroomed. Politicians were only too happy to encourage this in order to satisfy their constituencies. But there was no corresponding change at the public-school level to guarantee that more students would be prepared for university. High school grades edged up to meet entrance requirements, which edged down. As first- and second-year classes ballooned to hundreds and even thousands of students, multiple-choice testing replaced substantive testing, allowing students like Mary to get by. What gets lost in this apparent win-win situation of increasing enrollment is the pain of failure and near failure, and the cost of continuing to struggle against the odds to stay in school.

The effects on Mary are palpable. “Over my three years here, I’ve had dozens of anxiety attacks and my university counsellor wants to refer me to a psychiatrist to test me for depression – sometimes I just can’t face another class.”

Universities and colleges are seeking to better serve students like Mary by creating innovative help centres on campus that offer everything from writing workshops, to essay help for ESL students, to general psychological and practical skills counselling in such things as time and emotion management. Many of these helpers are more than willing to badger professors into giving extensions, make-up tests and other forms of consideration to ensure their charges make it through the system. They have a vested interest in keeping those tuition cheques rolling in, but it is debatable whether they are doing anything to improve these students’ long-term prospects.

As James Coté and Anton Allahar, sociology professors at the University of Western Ontario, argue, what is at work here is a disengagement compact: students are encouraged to feel entitled to decent grades regardless of their abilities or work ethic while professors water down their requirements to meet grade distribution quotas and to avoid confrontation with the students or their myriad defenders. Professors get caught in the middle as “gatekeepers to the world of middle-class, white-collar work.” No one wants to be the one to close the gate.

After getting one post-secondary degree, certificate or diploma, graduates increasingly find that doors do not fly open the minute they doff their graduation caps. Many return for more of the same out of desperation or vain hope. Indeed, master’s and doctoral programs are expanding at a faster rate than undergraduate programs. In 2004, Canada produced 4,200 PhDs – a 7.7 per cent increase over 2003. Graduate expansion has become the new buzzword at Canada’s larger universities. They are most interested to attract foreign students who pay on average three times more for the same degree. As a consequence, the size of graduate classes is beginning to exceed upper-year undergraduate classes. Gavin Smith, a professor at the University of Toronto, walked into a graduate class last autumn to discover 40 masters and doctoral students crammed into a seminar room designed for 20 – he was used to teaching fewer than 10. “You can’t treat graduate teaching the same way as undergraduate,” he said. “By this level, the point is not to listen to me give a lecture but to engage with the material and each other actively – 40 people can’t do that effectively.”

The post-secondary system is bulging with both students and irresolvable contradictions. The labour market of the past is gone and in its place are huge numbers of lower-paid, temporary, part-time jobs with few benefits and no security – what is known as contingent work. At the same time as this has unfolded, young Canadians have been encouraged to believe that if they just get better educated, they’ll be okay. But at the end of the degree, many are faced with few real prospects. Some will eventually climb out of contingent work and out of debt. Some will undoubtedly get the job in their field that makes it all worthwhile. But the statistics are not promising and the costs are very high.

If the mid-level jobs aren’t there, why is post-secondary education seen as essential for Canada’s economic future? Why does everyone from the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada to the Canadian Alliance of Student Associations to the Steelworkers Union call for increased funding and incentives for post-secondary education? Why is it politically savvy to increase student loans and grants, as the federal Minister of Human Resources, Diane Finley, has recently done? Apparently, we’ve all bought the story about Canada’s future as a knowledge economy.

This all suits the private sector, of course. They’ve done quite well thanks to the explosion of indebted, underemployed post-secondary graduates. In the good old days, companies would hire people out of high school (or before) and invest the time and energy to train them. The idea was that you created loyal employees who would advance gradually through the ranks as they learned more about company operations. Gradual advancement and job security were the employees’ rewards for sticking with the company, while a tailor-made fit with company operations was the company’s reward for expending the money and energy to train workers. These days, corporations want neither to offer secure employment nor take the time to train. By insisting on post-secondary qualifications for larger and larger numbers of jobs, businesses have transferred the costs of what is increasingly considered to be “basic” training to individuals and families, some of whom can ill afford to absorb them.

Rather than warehousing our youth in costly institutions, and rather than absorbing the costs of training that businesses used to pay, wouldn’t our efforts be better spent working to improve employment opportunities for all? We should be mobilizing against contingent work in all sectors by raising minimum wages and benefits and cracking down on the conversion of full-time to part-time work. We should be asking for government initiatives to bring innovative manufacturing back to our shores and supporting unionization of service work to improve working conditions. In short, we should be working toward a world where young Canadians do not have to sell their souls or drive themselves crazy for the right to work and live comfortably.

Post-secondary education won’t solve any of these problems. It undoubtedly has a place in our society and our economy, but for many, the blind pursuit of a higher education at any cost may do more harm than good.

All post-secondary students’ names have been changed at their request.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)