Various talking heads have proclaimed that the worst of the global recession may be over, but the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) maintains that “employment is the bottom line of the current crisis,” which has the potential to turn “into a long-term unemployment crisis.” The International Labour Organization (ILO) has also warned about an employment crisis. ILO director-general Juan Somavia this summer estimated that not only will there be about 239 million job losses globally due to the recession, but another 200 million people will be forced into deeper levels of poverty. Unless there is a concerted job-creation push by governments, the ILO estimates it will be between 2017 and 2020 before the world sees an end to the employment crisis.

The ILO answer to this disaster in the making is the Global Jobs Pact, which, if widely adopted, could represent a major step forward for working people, the economy and the environment.

The Global Jobs Pact has been adopted by 183 countries, including Canada, through organizations such as the G8, the G20 and the United Nations Social and Economic Council. Its objective is to protect existing jobs and stimulate further job creation in order to shorten “the usual lag time of several long years between growth recovery and employment recovery.” The non-binding agreement provides a variety of proven approaches that governments can utilize to protect jobs. Adopting “social justice as a guiding concept,” the agreement suggests approaches such as “supporting job-seekers through training and skills development; expanding employment guarantee schemes; and focusing special attention on young people and vulnerable groups.”

Other approaches advocated include supporting sustainable enterprises and investing in the green economy, food security and rural development. The Pact calls on wealthier nations to help poorer nations make employment a priority by providing financial assistance for stimulus measures. It also encourages spending on infrastructure projects, with a particular focus on health, education and social services.

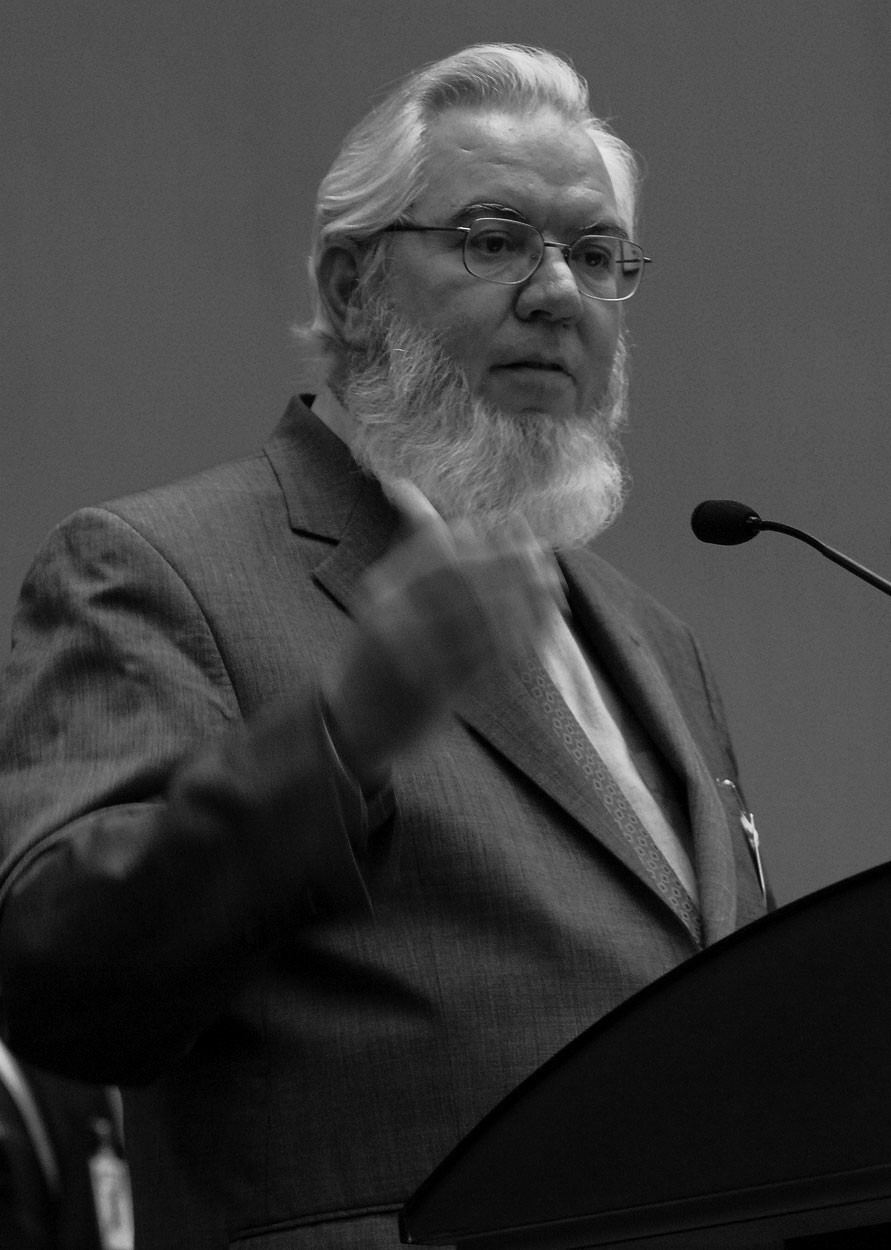

The Global Jobs Pact was drafted by government, business and labour representatives at the ILO in June of this year. Though it is not a binding agreement, Somavia describes it as “a collective policy commitment … to make employment creation and social protection a central element of all economic and social policies.” The ILO sees the Pact as “not an end to globalization, but a different, better globalization, a fairer, greener, and sustainable globalization with a moral compass; without the imbalances that have led to this crisis.”

Most in the labour movement have embraced the Pact, but there are a few skeptics. The Canadian Labour Congress (CLC), for instance, is concerned that recent signs of economic recovery mean the more progressive measures of the Pact will not be implemented. “It is clear to the ILO that Canada won’t be moving on the Jobs Pact without being pushed,” said Lucien Royer, director of the CLC’s international department. “We will need to pressure the government of Canada through legal means.”

The Canadian government’s labour website does not even mention the Global Jobs Pact that it has adopted, a fact that did not surprise Royer. “Canada is one of the top violators of ILO conventions.” As he sees it, “it is up to unions and civil society to push for the Jobs Pact, and to make it an election issue.” Canada is not the only country that will need to be challenged to follow through on the Pact.

One organization that has enthusiastically embraced the Pact is the International Federation of Chemical, Energy, Mine and General Workers’ Unions (ICEM). According to ICEM’s information officer, Dick Blin, “the way to prevent it from becoming lip service is for the labour movement to keep up the pressure on governments to follow through on the agreement.”

There are a few obstacles to seeing the Pact become a force for good in the world. There are countries, like Canada, that adopt the Pact but fail to implement it. Even more disruptive is that fact that poorer countries seeking to borrow emergency funds are being pressured to enact “austerity measures” (cuts in government spending) contrary to the spirit of the Pact. These cuts often serve only to put an already vulnerable population at greater risk. The Ukraine, for instance, borrowed $2 billion U.S. from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) earlier this year. As a condition of the loan, the IMF required reductions on government spending that resulted in the loss of financial assistance to poor families to help them pay for heat and hydro. Gas prices and the retirement age were also required to be raised.

Even in countries that have moved aggressively to protect employment, stimulus measures have not prevented job losses, nor the trend towards part-time, precarious employment. The OECD said that most of its members used measures such as “temporary cuts in employers’ social security contributions and short-time working subsidies to compensate workers for working fewer hours or to encourage the firms to hire.” These are working, the OECD says, but are not enough. The OECD is recommending the provision of assistance to youth to avoid “a lost generation.” The organization also has urged that social safety nets be reinforced, and advocates spending more on job search assistance, training and skills development.

Researchers from Oxford University recently released a landmark study of the social effects of rising unemployment. The study found that failure to protect the unemployed would result in a rising death toll from suicides and homicides around the world. The study, “The public health effect of economic crises and alternative policy responses in Europe,” is thought to be the most comprehensive evaluation of the relationship between economic crises, unemployment and mortality in Europe. It is also the first study to examine the role of specific government responses. Researcher David Stuckler told Science Daily, “Our findings show that investing in active labour market programmes can both help the economy and save lives.”

The Global Jobs Pact consists of a catalogue of proven employment-generating policies that have been adopted in principle by world leaders. But what has been the impact so far of government efforts to protect employment? The ILO reported to the G20 in September that G20 government actions saved 7 to 11 million jobs in 2009, although these figures are dwarfed by expected global job losses of 239 million. The ILO acknowledges that more must be done, particularly the protection of the vulnerable and the provision of assistance to poor countries.

According to Somavia, “stabilizing financial markets and raising the rate of output growth … are not enough. Financial markets have to be put at the service of the real economy.” Somovia also warned against half measures: “if the special measures taken are … withdrawn too early, the jobs crisis may worsen even further. For people worldwide, and in particular for the most vulnerable and disadvantaged, the crisis will not be perceived as receding until they get a decent job and a minimum floor of social protection. A jobless recovery would not be socially or politically sustainable.”

In other words, governments seeking to avoid major political and social upheavals would do well to follow closely the measures outlined in the Global Jobs Pact.